LOS ANGELES — Terrence Malick movies take a long time to gestate. Malick typically shoots hours and hours of footage, much of it improvised, and he then spends months editing it together. And in a career that goes back 33 years, he has directed only four films: Badlands, Days of Heaven, The Thin Red Line and, now, his version of the Pocahontas legend, The New World.

LOS ANGELES — Terrence Malick movies take a long time to gestate. Malick typically shoots hours and hours of footage, much of it improvised, and he then spends months editing it together. And in a career that goes back 33 years, he has directed only four films: Badlands, Days of Heaven, The Thin Red Line and, now, his version of the Pocahontas legend, The New World.

Sometimes the editing continues long after the film has been screened for critics. The New World was about two and a half hours long when it opened in late December for a one-week run in Los Angeles and New York, to qualify for last year’s Academy Awards. But this week, the studio is releasing a somewhat shorter version. And the tweaking doesn’t stop there: some members of the film’s cast say it may be as long as three hours when it is released on DVD.

So, this article is based on a version of the film that might never be seen again. But it should be safe to say that The New World, in whatever form, is of a piece with Malick’s other films, which emphasize visual poetry over more conventional forms of drama or narrative. For Malick, plot and character are less important than memory and experience.

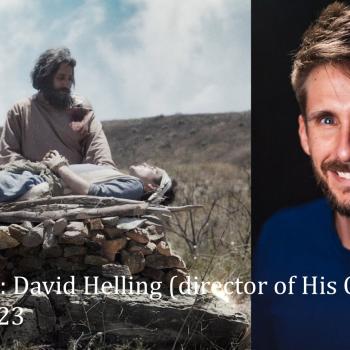

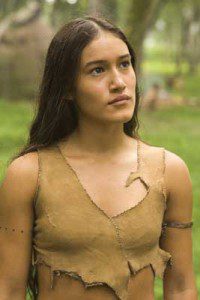

Malick’s dream-like visual style, and the way he holds seemingly unrelated images together through contemplative voice-overs, make for challenging viewing. But in some ways, The New World is one of his more accessible films. The story is rooted in the legendary — and almost certainly unhistorical — romance between Pocahontas (Q’Orianka Kilcher), the teenaged daughter of a Native chieftain, and John Smith (Colin Farrell), an Englishman struggling to maintain control of the nascent English colony of Jamestown.

Malick is notoriously reclusive and almost never does interviews, and Farrell checked into rehab just a few days before the film’s press junket. So it falls to Kilcher, a 15-year-old sitting down for the first round-table interview of her entire career, to be the film’s public face — and she says working with Malick was just as challenging as watching his films, but also somewhat liberating.

“He was a very spur-of-the-moment kind of director,” she says. “If he saw the wind blowing in the grass a certain way, he would all of a sudden start filming it. You would have to be ready for anything, and that was really great, because I love acting on my impulses, at the risk of being wrong or Terry not liking it. So it was really like, as he said, two artists making music together.

“We stayed pretty close to the script,” she adds, “except almost all the dialogue was cut out. He was like, ‘Oh, Q’Orianka, maybe just say this one line and don’t say anything else.’ And that, in itself, was almost a whole new language, because you had to really internalize what you were saying and think about it and try to convey it through expressions and movements.”

In the film, as in history, Pocahontas eventually converts to Christianity and marries an English tobacco farmer named John Rolfe (Christian Bale) — though the significance of these actions is debated by historians and even by the people who collaborated on this movie.

Kilcher says she identified with Pocahontas’s struggle to find and hold on to her true identity, because teens like her also have to cope with competing cliques and social standards. And, she says she thought it was “sad” when Pocahontas switched religions and began to live like an Englishwoman.

“That was the only thing left to her in a sense, because her family cast her out, John Smith left her, and so she was left, really, with nothing,” says Kilcher. “And that was the next thing to do, to get married to John Rolfe, because it was a stable thing, and it was kind of an instinct of survival. She had nowhere else to go. Once she decided to put on the English clothes and she was living with them, it was expected of her to become a confined English woman named Rebecca, and become baptized, and speak proper English.”

Producer Sarah Green has a slightly different take on Pocahontas’s conversion, though. “She absolutely voluntarily chose” to convert, says Green, who adds that the length of the movie didn’t allow the filmmakers to explore that aspect of the story in more depth.

“She was interested in Christianity, and she converted not just to marry John Rolfe, or not because she was a victim, but because she was drawn to that. I mean, that’s not the case obviously with many Natives — it was very different — so we simply show her in that process as much as we could really explore in this movie.”

I ask why the Pocahontas of the film continues to pray, in voice-over, to the sun and to an unspecified “mother” — her human mother? mother Earth? — even after her conversion, and why the film offers no indication that Pocahontas has internalized her Christianity.

“That’s an interesting question,” says Green, “and I, not knowing enough about her in reality, I can’t say how she [dealt with that]. But I imagine she melded those two. That’s what often happens in Native cultures with conversion, is that they meld what they know as their spirituality with this new spirituality that they’re learning, and I believe that she just found a way to integrate them.”

Malick’s films often use Edenic imagery to suggest that his characters yearn for innocence yet destroy it whenever they think they’ve found it. Few images in recent films are as striking as the moment when Smith, who has been away, returns to Jamestown and walks from an outside world of trees and grass into a fort that is paved with mud. What’s more, Smith finds that the colonists are starving, and have resorted to cannibalism.

At times, it may seem that Malick’s creative visual technique is just a cover for a trite and clichéd mythology, little different from Disney’s version of the story, in which the Native Americans are pure-of-heart noble savages while the Europeans are evil or clueless defilers of the earth. But Green notes that Malick’s film is more complicated than that, and that it doesn’t necessarily advocate the utopianism expressed by some of its characters.

“There are accounts from that time,” she says. “Most of our referents were written accounts of that time from colonists, whether they were journal entries or letters home or whatever, and several of those exact words were in those accounts, whether it was Smith or several of the other colonists.

“And it reflects the naive way that they saw the Native community in the opening, and you’ll notice that that’s only in the beginning, when Smith is enamoured of this world. We’re in his mind, experiencing what he’s experiencing, that this is complete bliss, and as you see, we show very quickly that that is a much more sophisticated culture, and that he was in fact naive to think that there is no jealousy.”

Furthermore, the film depicts Pocahontas’s eventual husband, John Rolfe, as a decent and truly loving man, and it follows their story as they journey to England together to meet the King and Queen. Bale, who provided one of the voices for Disney’s Pocahontas over ten years ago, says he had never even heard of Rolfe until he read the script for this film — and he says his research into the character led him to believe that Rolfe was “a progressive man, spiritually.”

“Here was somebody who had a great deal of money in England, and a great lifestyle, who chose to leave that and go and live in a place where cannibalism has been taking place, and survival is not assured in the slightest. And the bravery, that he acts on his love for his Pocahontas and created the first union between the locals and the new arrivals — yeah, I find him to be a very impressive man,” says Bale.

“And also the fact that he has such maturity and true love for her, that he’s prepared to return to England, knowing that she may well see Smith and still be in love with him and leave him, but he loves her enough to know that he would never want to stifle her or live in any kind of lie between the two of them. He would rather be in pain himself, and heartbroken, but see her doing what she truly should be doing in life.”

Part love story, part historical epic, and part poetic rumination on the relationship between humanity and nature, The New World certainly isn’t for every taste. But it’s one of those rare major-studio movies that happens to be quite artful, and beautiful — a feast for the senses and the spirit alike.

— A version of this article was first posted at CanadianChristianity.com. You can also read “bonus quotes” from Kilcher, Bale, Green and Wes Studi here.