The Rev. George M. Docherty died this week at the age of 97. He is widely credited with giving a sermon in 1954 that inspired President Eisenhower and others to pass a law that year which added the words “under God” to the American Pledge of Allegiance. (The picture above shows Docherty and Eisenhower on the day of the sermon in question.)

Reading Docherty’s obituaries today, I was struck by two facts: one, he was a Scotsman, and two, he was pastor at the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington, DC when he gave his famous sermon.

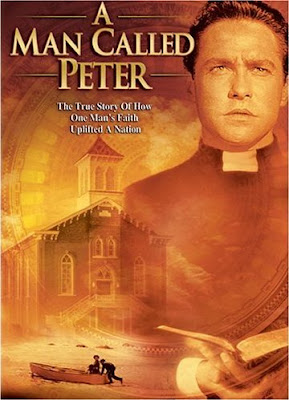

These two facts leapt out at me because they reminded me of Peter Marshall, a Scotsman who led that same church from 1937 until his death in 1949. His widow, Catherine Marshall, told his story in A Man Called Peter, a book that was published in 1951 and turned into a major Hollywood film in 1955 — one year after Docherty gave his Pledge-altering sermon. (The film was directed by Henry Koster, a man who specialized in movies with a spiritual or religious element.)

Although the bulk of the film takes place in the 1930s and 1940s, it reflects the concerns of the 1950s, too — and now that I know Marshall’s successors were directly involved in getting the phrase “under God” added to the Pledge, the film’s political elements take on a whole new aura. I find myself wondering what sorts of conversations people at that church had about this film, when it came out. How much of the film reflected their past, and how much reflected their present?

Although the bulk of the film takes place in the 1930s and 1940s, it reflects the concerns of the 1950s, too — and now that I know Marshall’s successors were directly involved in getting the phrase “under God” added to the Pledge, the film’s political elements take on a whole new aura. I find myself wondering what sorts of conversations people at that church had about this film, when it came out. How much of the film reflected their past, and how much reflected their present?

I was always aware of the film’s political subtext in a broad, general sense, of course. It’s hard to miss the emphasis the film places on the political monuments of Washington, DC, or on the fact that Marshall’s church is said to be the place where Abraham Lincoln once worshipped.

I have also long been aware of the fact that this film reflects the heightened religiosity of the 1950s, even though it is set slightly earlier in American history. To put the film in context: Twice, within the film, Marshall refers to the fact that “In God We Trust” is printed on American coins. In 1956, just one year after the film came out, Congress passed a law making “In God We Trust” the national motto of the United States; and then, in 1957, the motto appeared on paper money for the first time ever. It stands to reason that the film was part of a broader cultural conversation that led to those things.

There is also a scene set in November 1941 where Marshall’s secretary tells him that “General and Mrs. Eisenhower” will be attending the St. Andrew’s Day dinner. Marshall delights in this news, but it is doubtful that Eisenhower’s attendance would have been all that big a deal at that time; if Wikipedia is to be believed, Eisenhower had only become a general — a brigadier general, to be specific — the previous September, and he was “far from being considered as a potential commander of major operations.”

I always figured this scene was put there simply because Eisenhower was an extremely popular president, on the verge of being re-elected, at the time of the film’s release. But now I wonder if the filmmakers had anything more specific in mind. How often did Eisenhower attend this church? Is it possible the filmmakers had the famous amendment to the Pledge of Allegiance in mind, and all that led up to it, when they wrote this scene?

Anyway. The film itself is, for my money, easily one of the best religious films to ever come out of the Hollywood studios. British actor Richard Todd is funny and charming as the title character, and he delivers Marshall’s sermons with conviction and enthusiasm. I like the movie for sentimental reasons, too: I grew up with it, and it was a favorite of my grandmother’s, as well.

I actually began a blog post on the film over a year ago, when I got a copy of the DVD, but I put it on the back burner. The gist of that post, trivial as it was, was that there was a big, big problem with the DVD cover — and to see what it was, you just have to be familiar with the dialogue in the following scene: