In one of the many recent books written by an atheist about Christianity (I forget which one), the author suggests that one should look with suspicion on any religion whose dominant and most recognizable symbol signifies violence, torture, and oppression. The importance of the cross to all Christians, regardless of their many important differences, is indeed worthy of attention.

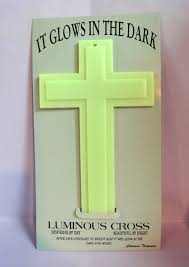

One of my early childhood memories involves waiting for a cross to arrive in the mail, selected from a list of gifts for having completed a Sunday school program successfully. Mail orders came slowly to rural Vermont in the early 60s—I recall anticipating its arrival for what seemed like an eternity.  For this was not just any old cross—it was a “glow in the dark” cross. Better than any nightlight, this cross would glow all night, keeping me company and reminding me of Jesus if I awakened in the middle of the night (which I almost never did). Or so the advertising claimed.

For this was not just any old cross—it was a “glow in the dark” cross. Better than any nightlight, this cross would glow all night, keeping me company and reminding me of Jesus if I awakened in the middle of the night (which I almost never did). Or so the advertising claimed.

When it arrived, I was immediately disappointed by its size. It was much smaller than I expected. I wasn’t expecting something life-sized—that wouldn’t have fit into my tiny bedroom. But I was expecting something larger than this six-inch flat white piece of plastic. It didn’t even have a stand to hold it upright. Instead, a flimsy gold thread was looped through a little hole on the top, about where “King of the Jews” was nailed on Jesus’ cross, which could be used to hang the cross on a wall.

Following the enclosed instructions, I placed the cross close to a lamp bulb for several minutes before retiring in order to get the full luminescent effect throughout the night. I then propped up my light-bulb-heated cross against a book on my nightstand, and turned out the lights.

I was suitably impressed with the steady glow from the cross, bright enough to shine a bit of light across the surface of the nightstand. I could have perhaps read by this cross light if I had moved it into my bed, but I wasn’t allowed to read after lights out. I laid on my back with my eyes closed, ready to soak up some Jesus rays, but soon had this odd sensation of something looking at me. Upon opening my eyes, I saw that the glow of the cross had dimmed to a hazy, other-worldly bluish tinge, sort of like the glow of deep sea monsters I’d seen pictures of in books. Very creepy. I took the cross and stuffed it under my pillow; the next morning, I stuck it in the back corner of my closet, never to be seen again.

The cross is a powerful symbol signifying that redemption comes through suffering. In my Baptist tradition, though, Good Friday was a minor speed bump on the way to Easter. It wasn’t until my twenties, when I first encountered Catholic Christians, that I learned the difference between a cross and a crucifix. Every cross I had ever seen was empty—that’s the point of the whole story, right?

But the Passion and Crucifixion, which we paid as little attention as possible to, is the sine qua non for the Resurrection. The genius of Christianity is that it does not seek a supernatural cure for suffering, but offers a supernatural use for it. God changes us by becoming one of us, and being human involves pain and suffering.

But Christianity is not just about the crucifixion either, despite evidence to the contrary in some sacred spaces I’ve visited. Facing anyone entering St. Catherine of Siena Hall, the philosophy and theology building on my campus, hangs a five-foot crucifix. It hardly causes me to think sacred thoughts, as it bears a striking resemblance to the garish crucifix that hangs crookedly over the narrow and steep stairs leading to the office of “The Penguin,” the hilariously intimidating and frightening nun who runs St. Helen of the Blessed Shroud orphanage in The Blues Brothers (my all-time favorite comedy movie).

A Catholic couple once described their church back home to me, full of gory crucifixes and related works of art, but noticeably lacking in anything referring to the resurrection. In a committee meeting, one of them reminded everyone that one of the Eucharistic responses is “Christ has died, Christ is risen, Christ will come again,” then suggested that while it was very clear from stepping into the church that the parishioners believed that Christ has died, they might want to consider adding something suggesting that they also believe that Christ is risen.

Hanging from the baldachin over the altar in St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota is a crucifix that satisfies both my Protestant sensibilities and my other-than-Protestant appreciation for liturgical arts and crafts. First, it rotates 360 degrees on its vertical axis, so that Jesus on the cross can face those in the choir stalls for daily prayers and liturgies, then turn around and face the sanctuary for Sunday services and larger celebrations. I watched a monk after last Sunday morning’s prayer take a forked pole about four or five feet long, grab the bottom of the crucifix with the pole and turn it 180 degrees to face the sanctuary. If I were a monk, that’s the job I would want—very cool.

This cross is large (as is everything in the Abbey), but Jesus is small and abstract, probably no more than two feet tall, seemingly ready to step or ascend from the cross at any moment. And, as it turns out, that’s exactly what he does. Several years ago, a monk revealed to me at dinner that Jesus on the Abbey cross is magnetic. He sticks to the cross securely, but is taken down during Lent.

Magnetic Jesus—what a concept. I wonder what magnetic Jesus does when he’s not sticking to the cross? Hold up menus on the refectory refrigerator? Keep monastic art projects securely in place on a community bulletin board? How powerful is his magnetism? Do the monks have to keep their credit cards and thumb drives at a safe distance? Just wondering.

Because she was an experienced church-going parent, my mother’s pocketbook contained various items carefully selected for the pacification and entertainment of fidgety and bored children in church. Guaranteed to work, at least for me, were two tiny plastic Scottie dogs, one white and one black, each standing on a rectangular magnet. I was endlessly fascinated by their love/hate relationship, how when I brought them together in one way they instantly repelled each other, while in the opposite way they attached as if they’d been made for each other.

Our relationship with the divine is like that. We are spiritually equipped with hearts that are God-magnets, hearts that God cannot approach when they are turned self-ward. But when we turn our hearts outward, we attract the divine from every place imaginable. I seldom agree with Augustine, but at the beginning of his Confessions he expresses this dynamic well: “My heart is restless until it finds its rest in you.”