Although I regularly find myself immersed in things medieval with a bunch of freshmen every spring, I am not a medievalist. I must confess that I often find medieval literature, philosophy, theology, and just about everything else medieval largely boring, inscrutable, or both. Still, it’s hard to go wrong in the classroom studying Dante’s Inferno with eighteen-year-olds. Sin, violence, torture—what could be better? Is suicide worse than lying? Is adultery less problematic than treason? How do gluttony and simony compare? Does sloth trump cowardice? Great discussion material.

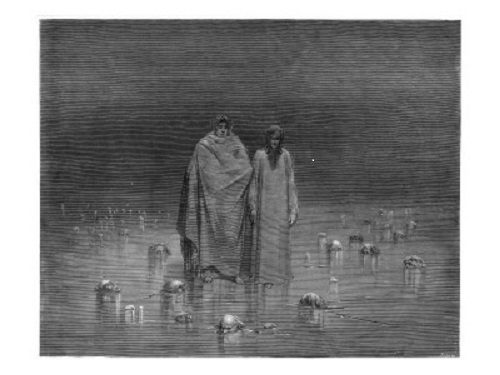

Every time I descend into Hell with the Pilgrim and Virgil, my attention is drawn to something different. Last semester, I took special notice of the first bunch of folks Dante encounters. Squeezed into Canto III, between a trio of threatening beasts and the virtuous pagans, we find “those sad souls who lived a life but lived it with no blame and with no praise,” lives so non-descript that neither Paradise nor Hell wants them. These are “wretches who had never truly lived” whose sins or faults don’t even rise to the level of getting a name. Call them the “Whatevers” who never committed themselves to anything. Their actions were neither good enough to earn praise nor bad enough to require mercy or justice. These are “wretches who never truly lived; the world will not record their having been there.” The Whatevers remind me of the Laodicean church in the Book of Revelation, about which God says “I know your deeds, that you are neither cold nor hot. So, because you are lukewarm—neither hot nor cold—I will spit you out of my mouth.”

It was the fear of spending eternity in the land of the Whatevers that motivated Henry David Thoreau to shake things up in his life. He begins Walden with “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” Several summers ago Jeanne and I stayed at a lovely bed and breakfast—furnished with a wonderful hostess, hundreds of feeding birds and at least a half-dozen Chihuahuas—literally across the road from Walden Pond.

On the other side of the pond, about a half-mile from where we were staying, Jeanne and I got to see the foundation and stone chimney of the tiny hovel Thoreau built for himself when he went to the woods. But Thoreau had the luxury to go to the woods in the first place, hardly a wilderness, since Walden Pond is only three or four miles from Concord, where Henry David could get a free meal at Ralph Waldo Emerson’s house any time he chose. These are luxuries that most of us do not have. Is it possible to learn to live deliberately without removing oneself from real life?

In his very interesting novel Putting Away Childish Things, theologian Marcus Borg frequently drops favorite book titles, excerpts and poems into the lives of his various characters. One of the poems is Mary Gordon’s “When Death Comes,” portions of which resonate with me more strongly than Thoreau’s more famous lines on the same theme.

When death comes

Like the hungry bear in autumn;

When death comes and takes all the bright coins from his purse

To buy me, and snaps the purse shut . . .

I want to step through the door full of curiosity, wondering:

What is it going to be like, that cottage of darkness . . .

When it’s over, I want to say; all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.

When it’s over, I don’t want to wonder

If I have made of my life something particular, and real.

I don’t want to find myself sighing and frightened,

Or full of argument.

I don’t want to end up simply having visited this world.

I often wonder how I’m doing with this business of “making my life extraordinary,” as Mr. Keating challenges his young students to do in my all-time favorite movie, Dead Poet’s Society. On the first page of Walden, Thoreau writes that he wants to “suck the marrow out of life,” something that never sounded particularly attractive to me. “Suck the marrow out of life” sounds a lot like “Be all that you can be,” or “Go for the gusto”—a call to fill my life with as many various and diverse experiences as possible, never stopping for a breath until I don’t have any breaths left.

I guess I’m not a “marrow-sucking” kind of person. An extraordinary life need not be bursting at the seams with things purchased, places visited, or frequent flyer miles—although there is nothing wrong with any of these. My mantras for an extraordinary life have become “Be where you are” and “Do what you are doing.” Pay attention. Be aware. In the busyness of the day don’t forget that each moment in class might be the moment that transforms someone’s life. Take notice that every “like” clicked on my blog means that someone, somewhere, read what I wrote and liked something in it. Be thankful every day for the gift of spending so many years of my life married to an extraordinary human being. Don’t ignore the multiple signs that my sons have become wonderful men.

The older I get the more I find myself drawn, when thinking about my mortality, to Psalm 90. I first consciously encountered this Psalm nine years ago during noon prayer with a bunch of Benedictine monks; it was one of the psalms when I shared morning prayer with those same monks last Saturday. After spending the first several verses reminding us that humans are “like the grass; in the morning it is green and flourishes; in the evening it is dried up hat hand withered,” the Psalmist drops the hammer. “The span of our life is seventy years, perhaps in strength even eighty; yet the sum of them is but labor and sorrow, for they pass away quickly and we are gone.” And have a nice day.

But the suggested response in verse twelve makes all the difference. “So teach us to number our days, that we may apply our hearts to wisdom.” I’ve come to realize that numbering my days is not about trying to guess how many I have left. Rather, it is about treating each day as the unique gift that it is—that opens the door toward wisdom. Be where you are. Do what you are doing.

When it’s over, I will have been more than a visitor to this world if I have taken attentive ownership of the small piece of it given me during my lifetime. I only ask what the Psalmist asks at the end of Psalm 90: “May the graciousness of the Lord our God be upon us; prosper the work of our hands; prosper our handiwork.” And please deliver me from the land of the “Whatevers.”