But understand this, that in the last days terrible times will come. For people will be lovers of self, lovers of money, proud, arrogant, abusive, disobedient to their parents, ungrateful, unholy, heartless, unappeasable, slanderous, without self-control, brutal, not loving good, treacherous, reckless, swollen with conceit, lovers of pleasure rather than lovers of God, having the appearance of godliness, but denying its power. Avoid such people. II Timothy 3:1-5

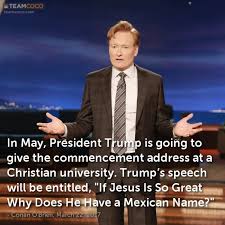

Hardly the description of a person one would expect to be giving the commencement address at the largest evangelical Christian university in the world.  And yet there was Donald Trump—who could arguably use the Apostle Paul’s words on his resume as a self-description—a bit over a week ago on Mother’ Day eve, speaking to the graduates at Liberty University, the Lynchburg, VA creation of Moral Majority founder Jerry Falwell, who established the school as Liberty Baptist College almost fifty years ago. The university now has over 15,000 residential undergraduate and more than 100,000 online students. The reaction of the more than 50,000 people in attendance at the commencement held in the university’s football stadium when the President walked on stage sounded like the Beatles had just arrived. They cheered when, in his summary of Trump’s accomplishments in his first four months as President, Chancellor Jerry Falwell, Jr. praised Trump for bombing “those in the Middle East who were persecuting Christians” (even though the expressed reason for the bombing was Syrian president Assad’s use of chemical weapons on his own citizens).

And yet there was Donald Trump—who could arguably use the Apostle Paul’s words on his resume as a self-description—a bit over a week ago on Mother’ Day eve, speaking to the graduates at Liberty University, the Lynchburg, VA creation of Moral Majority founder Jerry Falwell, who established the school as Liberty Baptist College almost fifty years ago. The university now has over 15,000 residential undergraduate and more than 100,000 online students. The reaction of the more than 50,000 people in attendance at the commencement held in the university’s football stadium when the President walked on stage sounded like the Beatles had just arrived. They cheered when, in his summary of Trump’s accomplishments in his first four months as President, Chancellor Jerry Falwell, Jr. praised Trump for bombing “those in the Middle East who were persecuting Christians” (even though the expressed reason for the bombing was Syrian president Assad’s use of chemical weapons on his own citizens).  If anyone in the crowd disagreed with Falwell when he said that “I do not believe that any President in our lifetimes has done so much that has benefitted the Christian community in such a short time span than Donald Trump,” they kept their mouths shut.

If anyone in the crowd disagreed with Falwell when he said that “I do not believe that any President in our lifetimes has done so much that has benefitted the Christian community in such a short time span than Donald Trump,” they kept their mouths shut.

In some ways, the President’s address was boilerplate Trump—he seldom went more than three sentences without mentioning himself, remained committed to a sixth-grade vocabulary (using his favorite adjectives “amazing” seven times and “great” twenty-seven times), spent the middle third of his talk praising Liberty’s beefed up football program, and more than once mispronounced the name of Fr. Theodore Hesburgh (calling him “Hesper”), who was the President of the University of Notre Dame for thirty-five years. His usual obsession with size was on display as he marveled at the size of the crowd, the number of graduating seniors seated on the field, that Liberty is bigger than Notre Dame, and the size of his upset victory last November. It was also a boilerplate commencement speech, complete with invitations for the graduates to applaud their thanks to their parents, appeals to patriotism, the perfunctory thanks to those in the military for their sacrifice and service,  phrases such as “the greatest adventure of your life” and “demand the best from yourself,” stories of people overcoming obstacles to achieve success, and no warnings about the fact that the lives the graduates were undoubtedly imagining for themselves going forward almost certainly will not turn out as they expect. In many ways, the President’s address was exactly like ninety-nine percent of all commencement addresses—completely forgettable.

phrases such as “the greatest adventure of your life” and “demand the best from yourself,” stories of people overcoming obstacles to achieve success, and no warnings about the fact that the lives the graduates were undoubtedly imagining for themselves going forward almost certainly will not turn out as they expect. In many ways, the President’s address was exactly like ninety-nine percent of all commencement addresses—completely forgettable.

But woven into Trump’s rambling remarks were regular references to something that has been a conservative Christian theme for some time—the perception that Christians are under attack. This was not Trump’s first visit to Liberty University. When speaking at the university’s convocation in January 2016, then candidate Trump was clearly still searching for his sea legs trying to speak the language of the conservative Christian. He referred to his favorite Bible verse in “Two Corinthians,” for instance; critics suggested that someone might have wanted to tell him that the proper reference is  “Second Corinthians” in preparation for speaking before a crowd of Bible-toting evangelicals. Trump’s commencement address showed that the President can learn a few new tricks—his speech was filled with the code words and phrases that evangelical Christians recognize as marking one of their own. Predicting that the graduates would be “warriors for truth . . . for our country, and for your family,” Trump frequently challenged the graduates to be “true champions,” suggesting that Liberty University’s creed is “to be, really, champions for Christ” (the banner behind the podium said “Liberty University: Training Champions for Christ since 1971”). Over and over the President challenged the graduates to embrace the role of “Outsider,” an odd role to assign to evangelical Christians, since the latest Pew Research data reveals that 25.4% of Americans are evangelical Protestant Christian, the single largest religious group in the nation. Trump promised the graduates that as long as he is president, “no one is ever going to stop you from practicing your faith or from preaching what’s in your heart.

“Second Corinthians” in preparation for speaking before a crowd of Bible-toting evangelicals. Trump’s commencement address showed that the President can learn a few new tricks—his speech was filled with the code words and phrases that evangelical Christians recognize as marking one of their own. Predicting that the graduates would be “warriors for truth . . . for our country, and for your family,” Trump frequently challenged the graduates to be “true champions,” suggesting that Liberty University’s creed is “to be, really, champions for Christ” (the banner behind the podium said “Liberty University: Training Champions for Christ since 1971”). Over and over the President challenged the graduates to embrace the role of “Outsider,” an odd role to assign to evangelical Christians, since the latest Pew Research data reveals that 25.4% of Americans are evangelical Protestant Christian, the single largest religious group in the nation. Trump promised the graduates that as long as he is president, “no one is ever going to stop you from practicing your faith or from preaching what’s in your heart. We will always stand up for the right of all Americans to pray to God and to follow his teachings”—as if the thousands of evangelical Christians in the audience were regularly being denied any of those things.

We will always stand up for the right of all Americans to pray to God and to follow his teachings”—as if the thousands of evangelical Christians in the audience were regularly being denied any of those things.

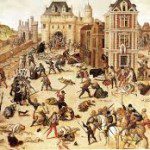

Evangelical Christians voted for Trump in November in massive numbers, as responsible for his electoral college victory as any other single demographic. There were undoubtedly many reasons why they voted for a man who has regularly and publicly said and done things that are a disgrace and affront to even the most basic Christian principles throughout his adult life; one of these reasons is that Trump’s packaging of reality in an aggressively “Us vs. Them,” “Winners and Losers” framework fits the evangelical’s natural disposition to imagine faith as something to be defended and protected against all manner of perceived threats. I am very familiar with this version of Christianity—it is the one in which I was raised. I learned at a very early age that Christians are involved in a cosmic war between the forces of good and those of darkness—we talked a lot about “spiritual warfare.”  Many of the hymns of my childhood shared a common theme—we Christian believers are at war and must be prepared to do battle at any moment. From “Lead On, O King Eternal” and “Onward Christian Soldiers” through “Soldiers of Christ, Arise,” to “Who is On the Lord’s Side?” I learned a spiritual vocabulary of aggression, violence and warfare. I was never clear about exactly who we were supposed to be fighting or how to recognize the enemy, but I knew I had been drafted into an army, whether I liked it or not. Almost five centuries ago, as he observed his fellow French Catholic and Protestant citizens regularly kill each other in the wake of the Protestant Reformation,

Many of the hymns of my childhood shared a common theme—we Christian believers are at war and must be prepared to do battle at any moment. From “Lead On, O King Eternal” and “Onward Christian Soldiers” through “Soldiers of Christ, Arise,” to “Who is On the Lord’s Side?” I learned a spiritual vocabulary of aggression, violence and warfare. I was never clear about exactly who we were supposed to be fighting or how to recognize the enemy, but I knew I had been drafted into an army, whether I liked it or not. Almost five centuries ago, as he observed his fellow French Catholic and Protestant citizens regularly kill each other in the wake of the Protestant Reformation,  Michel de Montaigne wrote that “there is no hostility so extreme as that of the Christian.” To which a contemporary evangelical Christian might respond by asking “And what’s your point? When one is at war, hostility is to be expected.”

Michel de Montaigne wrote that “there is no hostility so extreme as that of the Christian.” To which a contemporary evangelical Christian might respond by asking “And what’s your point? When one is at war, hostility is to be expected.”

To be fair, there are enough New Testament texts—particularly in Paul’s epistles—using such aggressive language to describe the life of following Jesus to perhaps justify framing the Christian life in a manner at the same time both combative and defensive. But in the words attributed to Jesus in the gospels, one finds something very different. The kingdom of heaven that Jesus describes is radically inclusive—all are welcome—and this kingdom is our business to establish now, not to hope for at some future post-apocalyptic date. Jesus regularly turns his closest followers away from defensiveness and aggression toward acceptance and welcome. In two of my classes this semester, I more than once had the opportunity to explore with my students how Jesus describes the kingdom of heaven in his parables and stories. The kingdom of heaven is like a mustard seed , like salt, like leaven—in other words, like things so tiny and apparently insignificant that one might entirely overlook them. Most importantly, these things do their slow and transformative work embedded in what they are working on, not by protecting themselves from it or aggressively attacking it. By becoming part of the mixture of flour, water, and other ingredients, yeast transforms them into something more than the sum of its parts. The kingdom of heaven, in other words, is not a zero sum game. It is a both/and kingdom.

, like salt, like leaven—in other words, like things so tiny and apparently insignificant that one might entirely overlook them. Most importantly, these things do their slow and transformative work embedded in what they are working on, not by protecting themselves from it or aggressively attacking it. By becoming part of the mixture of flour, water, and other ingredients, yeast transforms them into something more than the sum of its parts. The kingdom of heaven, in other words, is not a zero sum game. It is a both/and kingdom.

I have no idea whether Donald Trump takes any of the religious-sounding rhetoric in his Liberty University commencement address seriously—I must say that if “by your deeds you shall know them,” his deeds have not been very promising. For those who do take their Christian faith seriously and have convinced themselves that their faith led them both to vote for and continue to support Donald Trump, remember that no one can serve two masters. Will it be the kingdom of Trump or the kingdom of heaven?