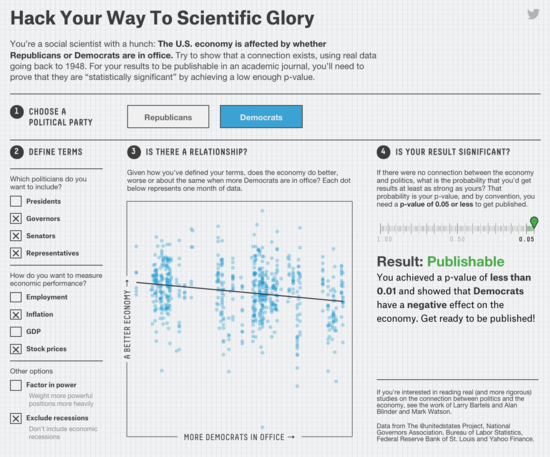

If you’re unfamiliar with how science publishing works, and how easily it could be manipulated (even by researchers who have only good intentions), you should check out this great piece by Christie Aschwanden at FiveThirtyEight.

Aschwanden explains how easy it can be in some situations to hack your way to “publishable” material from a set of data.

Scientists who fiddle around like this — just about all of them do, Simonsohn told me — aren’t usually committing fraud, nor are they intending to. They’re just falling prey to natural human biases that lead them to tip the scales and set up studies to produce false-positive results.

Since publishing novel results can garner a scientist rewards such as tenure and jobs, there’s ample incentive to p-hack. Indeed, when Simonsohn analyzed the distribution of p-values in published psychology papers, he found that they were suspiciously concentrated around 0.05. “Everybody has p-hacked at least a little bit,” Simonsohn told me.

It reminds me of this great XKCD strip I would show in my statistics classes:

There are ways for scientists (and journal editors) to protect themselves against their own biases in order to make sure they’re only publishing valid papers, but perhaps the more important thing is for the general public to realize that the headlines (which trumpet conclusions) don’t always match what’s really going on. If we can teach people to look behind the headlines and look at methodology and data, we’d all be better off.

Too bad that’s not happening anytime soon.

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."