Any book of the treatment of atheists throughout American history is bound to be extremely pessimistic. We were considered heretics then and we’re considered heretics now, though that’s slowly changing. But it’s worth revisiting that history just to understand how tough it was for the “New Atheists” of their time.

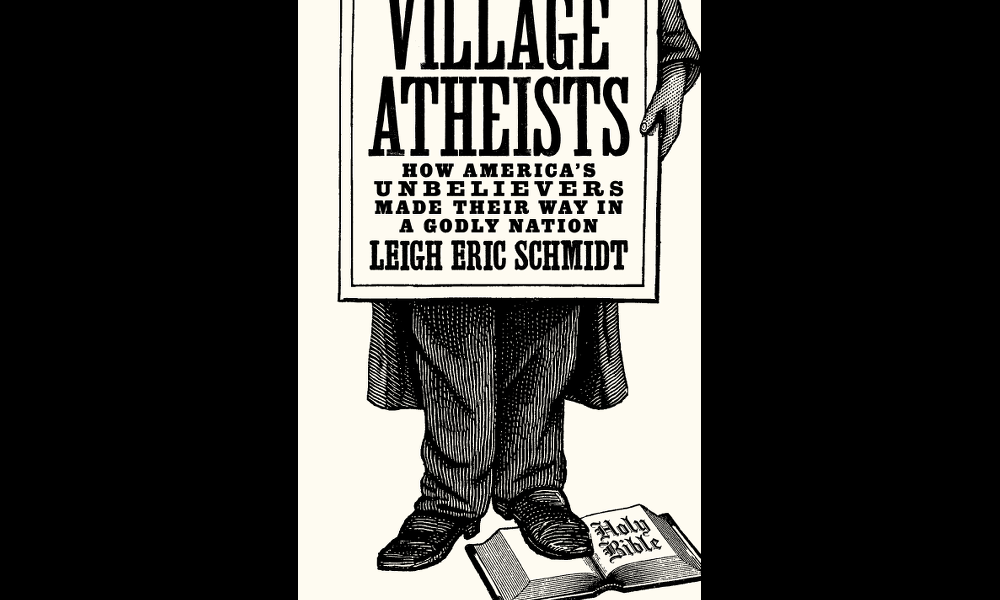

Washington University in St. Louis professor Leigh Eric Schmidt has looked at that history through the eyes of four outspoken critics of religion from more than a century ago, and he writes about them in a new book called Village Atheists: How America’s Unbelievers Made Their Way in a Godly Nation (Princeton University Press, 2016).

In the excerpt below, Schmidt talks about how, even long ago, atheists couldn’t agree on what to call themselves:

A word about naming. Nineteenth-century unbelievers tried out various designations for themselves — with inherited terms like “freethinker” and “atheist” finding company with newer labels like “liberal” and “agnostic.” At an Infidel Convention in Philadelphia in 1857, those in attendance stumbled over the growing confusion in nomenclature. “The time is now come for the Unbelievers, Infidels, or Liberals (or what name soever we may call ourselves by) to stand forth”; so began one resolution that came to the floor. This uncertainty over naming created a long discussion. “Infidel” was a slur (akin to “atheist”) that some thought should be resisted with more positive constructions of free inquiry, though most wanted to wear the badge proudly. “Liberal” was seen as the more irenic and encompassing term, but some thought it made resolute unbelievers look too amenable to religious associations and alliances (with, say, spiritualists or Unitarians). Two years later in 1859, when that small infidel association met again in Philadelphia, a resolution was floated suggesting that a new term of British coinage, “secularist,” be adopted as a more inclusive label than “atheist” or “infidel.” The assembled roundly dismissed that idea as “rank cowardice,” a lexicographer’s softening concession to Christianity, but their opposition did not prevent some infidels from trying out the new designation. The naming problem remained endlessly cloudy. One freethinker, puzzling in 1884 over the most appropriate label, wanted to “add a name of my own” to the mix of options; he recommended “true Americans” (it did not catch on). A journalist, looking back in 1933 on the irreligious agitators of the previous century, made light of all this slipperiness: “They could never even agree on what to call themselves. Freethinker, Rationalist, Agnostic, Atheist, Liberal, Secularist, Monist, Materialist — take your choice!” And that was to say nothing of Philanthropist, Positivist, Humanist, or Humanitarian.

However baffling in their profusion, the various tags were recognizably bound together through a set of shared attributes. Those commonalities included: (1) a rejection of Christian orthodoxy and biblical authority that passed from deism into atheism; (2) a very strict construction of church-state separation; (3) a commitment to advancing scientific inquiry as the pathway to verifiable knowledge and technological prowess; (4) an anticlerical scorn for both Catholic and Protestant power; (5) a universalistic imagining of equal rights, civil liberties, and humanitarian goodwill; and (6) a focus on this world alone as the domain of human happiness and fulfillment. Most freethinkers saw the sundry labels at their disposal as mutually reinforcing, as shorthand condensations of these overlapping aims, principles, and objections. A correspondent to the Boston Investigator in 1882, for example, wrote to ask the editor: “I would like to know if Secularism and Atheism mean the same thing?” To which the editor replied: “They mean the same so far as concerns any useful and practical purpose.” The various appellations were, in short, interdependent and routinely transposable. Everyday interchangeability trumped fine distinctions, no matter how often one contributor or another tried to sharpen the political or metaphysical significance of a given marker.

The use of the label “village atheist” in the pages and title of this book warrants particular comment and contextualization. The earliest reference to “the village atheist” occurred in an 1808 review of the work of the British clergyman and poet George Crabbe. His collection of Poems (1807) included “The Parish Register,” a richly descriptive account of the local characters surrounding an Anglican vicar in rural England. The Monthly Review called particular attention to Crabbe’s “masterful delineation of the village atheist,” though the poet had actually used the phrase “rustic Infidel” to depict this neighborhood lout:

Each Village Inn has heard the Ruffian boast,

That he believ’d ‘in neither God nor Ghost;

‘That when the Sod upon the Sinner press’d,

‘He, like the Saint, had everlasting Rest.The picture Crabbe painted of the “rustic Infidel” — a hearty companion of roadhouse quaffers, a libertine who considers “the Marriage-Bond the Bane of Love,” a supremely “Bad Man” who conflates “the Wants of Rogues” with “the Rights of Man” — possessed, to say the least, none of the nonconformist romance that Van Wyck Brooks’s depiction projected a century or so later. What “The Parish Register,” first published in the United States in 1808, did suggest was that the village atheist’s ancestry wound its way back into long-standing forms of impiety and profane living. Crabbe combined the scoffing irreverence of the tavern — the vulgarities of a Benjamin Sawser or an Elijah Leach — with the pigeonholes made for the deistic infidelity of Tom Paine and his acolytes. That combined image of sloshed blasphemer and Bible-ridiculing deist followed freethinkers out of the late Enlightenment deep into the nineteenth century. When Yale professor Henry A. Beers published his Outline Sketch of American Literature in 1887, he depicted “the village atheist” as a figure much like the one in Crabbe’s register — irreverent, half-educated, and pugnacious, with a well-thumbed copy of Paine’s Age of Reason in hand to inspire his harangues of the faithful.

Village Atheists is now available in bookstores and on Amazon. Be sure to also check out our recent podcast with Dr. Schmidt.

…

Excerpted from Village Atheists: How America`s Unbelievers Made Their Way in a Godly Nation. © 2016 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."