Ali A. Rizvi was raised in a Muslim family but became an atheist later in life. That’s not to say he harbors resentment about his upbringing — he still honors and practices many of the religious traditions he grew up with — but he also understands that there are extremists out there who have used the same holy books to commit unspeakable crimes. How can you be critical of the worst aspects of your faith without alienating all the peaceful Muslims out there?

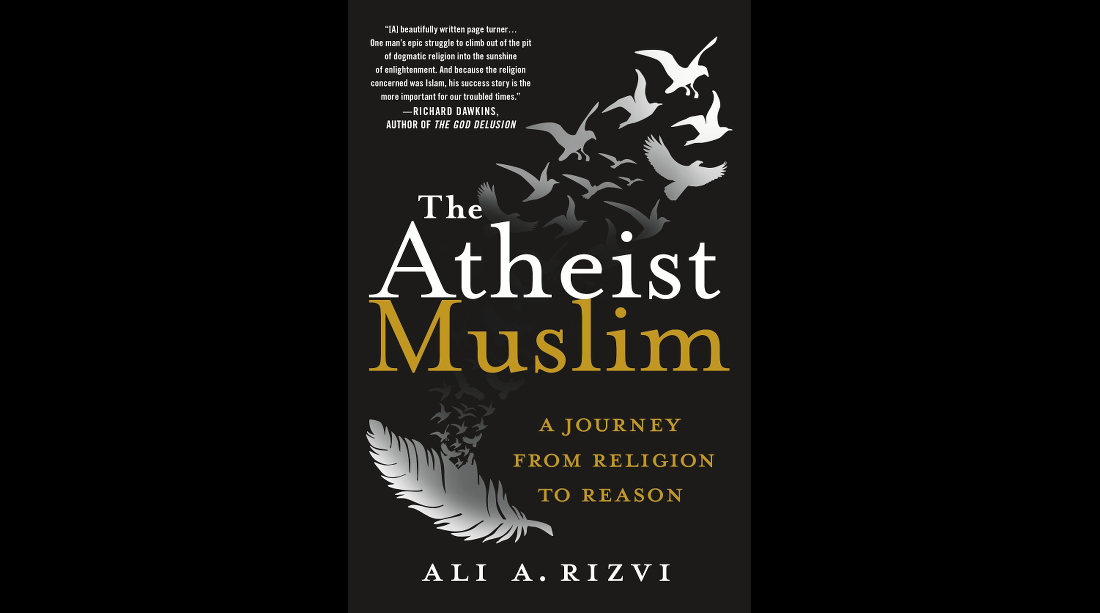

That’s the line he walks in his new book The Atheist Muslim: A Journey from Religion to Reason (St. Martin’s Press, 2016):

In the excerpt below, Rizvi tries to get inside the mind of a radical Muslim who supported the killing of children by Islamic terrorists, only to realize they have something in common.

I never truly grasped what it would be like to really believe in life after death — and I mean really believe in it — until shortly after the Taliban’s attack on the Army Public School in Peshawar, Pakistan, in December 2014. These murderers stormed into the school and shot dead 141 people, including 132 children, chanting, “Allahu Akbar!” as they shot each child.

After the attack, I had a conversation with a Taliban supporter online who was protesting my posts condemning the massacre; he defended it. He seemed sincere. Instead of brushing him off, I decided to engage him and ask him questions just to understand how his mind worked. I started by asking the obvious — why was he defending the killing of innocent people? His answer:

Human life only has value among you worldly materialist thinkers. For us, this human life is only a tiny meaningless fragment of our existence. Our real destination is the Hereafter. We don’t just believe it exists, we know it does. Death is not the end of life. It is the beginning of existence, in a world much more beautiful than this. As you know, the [Urdu] word for death is “intiqaal.” It means “transfer,” not “end.”

I asked him what right he had to decide that. Why was he making that decision for others? Shouldn’t they have the right to make that decision for themselves? And why children? They haven’t even had a chance to process what they’ve been taught, or make their own decisions. He justified it by saying these were children of army officers, who he believed were treasonous for fighting against the Taliban, Allah’s soldiers:

Paradise is for those of pure hearts. All children have pure hearts. They have not sinned yet… They have not yet been corrupted [by their apostate parents]. We did not end their lives. We gave them new ones, in Paradise, where they will be loved more than you can imagine…

They will be rewarded for their martyrdom. After all, we also martyr ourselves with them. The last words they heard were the slogan of Takbeer [Allahu Akbar]. Allah Almighty says Himself in Surah Al-Imran [3:169–170] that they are not dead.

The man was quoting verses from the Quran that state, “And never think of those who have been killed in the cause of Allah as dead. Rather, they are alive with their Lord, receiving provision, rejoicing in what Allah has bestowed upon them of His bounty, and they receive good tidings about those [to be martyred] after them who have not yet joined them — that there will be no fear concerning them, nor will they grieve.” There is another verse in the Quran, 2:154, that drives home the same point: “And do not say about those who are killed in the way of Allah, ‘They are dead.’ Rather, they are alive, but you perceive [it] not.”

This is where it hit me. I could not argue with this man unless I challenged the Quran. And if I challenged the Quran, I knew exactly how he would respond. It was a true deadlock, maybe even worse, considering one side genuinely believed it had divine endorsement on its side. There was absolutely no way to get through. He was quoting verses from a book that over a billion people in the world claim to be infallible, and this man took it very, very seriously.

I went back to talking about the fact that these were children. They didn’t choose to die in the way of Allah, and the jihadists had simply robbed them of the opportunity to make that decision. He didn’t think this seemed to matter, and indeed, the verses cited don’t seem to make the distinction either — they only speak of those “killed in the way of Allah,” irrespective of consent.

You will never understand this. If your faith is pure, you will not mourn them, but celebrate their birth into Paradise. But most of the people who call themselves Muslims do not believe this. They believe death is an end. This is because their faith is not pure.

The most chilling aspect of all of this was that everything he was talking about was what I had been taught growing up as a child: this life is temporary, just a test, heaven is infinitely preferable to life here and lasts forever, and death is not the end, but a transition to the afterlife. A lot of this doesn’t just apply to Muslims. When faced with the death of a fellow human being, it is almost cliché to hear consolers say, “She’s smiling and looking down at us from above,” or, “He’s in a better place now.” The difference between us saying this and the Taliban supporter saying it is that he really, really believes it. If death really gets us to a better place, why do we treat it as such a permanent thing? Why does our mourning have an intensity that is so far beyond a temporary separation after which we would be reunited? Why do we speak of our dead in the past tense? Why is death treated as a finality instead of a transition to something much better?

One could protest the man’s stance on killing children, of course, but is his view of death not identical to what we’re drumming into the heads of our children at Sunday school and the Friday mosque sermon? I remember asking my Islamic Studies teacher as a child, “What if children die? Do we also go to hell?” I was assured that we don’t, because we are yet too young to assume responsibility for our actions. But we did grow up celebrating our martyrs. The story of the martyrdom of Muhammad’s grandson Husayn is central to Shia Islam, similar to how the martyrdom of Christ is central to Christianity. My friends and I would talk about it. “When you die, how do you want to die?” The answer was clear.

“I want to be shaheed.” A word that means martyr, or one who dies in the way of Allah. And we weren’t even fundamentalists. We were regular, everyday kids from moderate to liberal Muslim families whose parents would ground us and commit us to psychiatric therapy if we so much as thought of joining a jihadist group. But this concept of being shaheed was never treated with anything less than great reverence.

This glorification of life after death isn’t just done by the Taliban, but by any Muslim who uses the words shaheed or martyrdom in a positive sense. When Muslims glorify the shaheed or the martyrs, they celebrate death over life, and they should be aware of how toxic this idea is when people really believe it, like my Taliban-supporting correspondent. The notion that this life on Earth is secondary to the afterlife — a fundamental tenet of many religious faiths — is deadly when it is genuinely and sincerely believed from the heart. I also believe this to be true of many other elements of religious belief.

The Atheist Muslim is now available in bookstores and on Amazon.

…

From THE ATHEIST MUSLIM by Ali A. Rizvi. Copyright © 2016 by the author and reprinted with permission of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."

It’s Moving Day for the Friendly ..."