This is the sixth installment of a series of posts by Dr. Yong on the theme of the “Holy Spirit and Mission in Canonical Perspective.” See all the posts here.

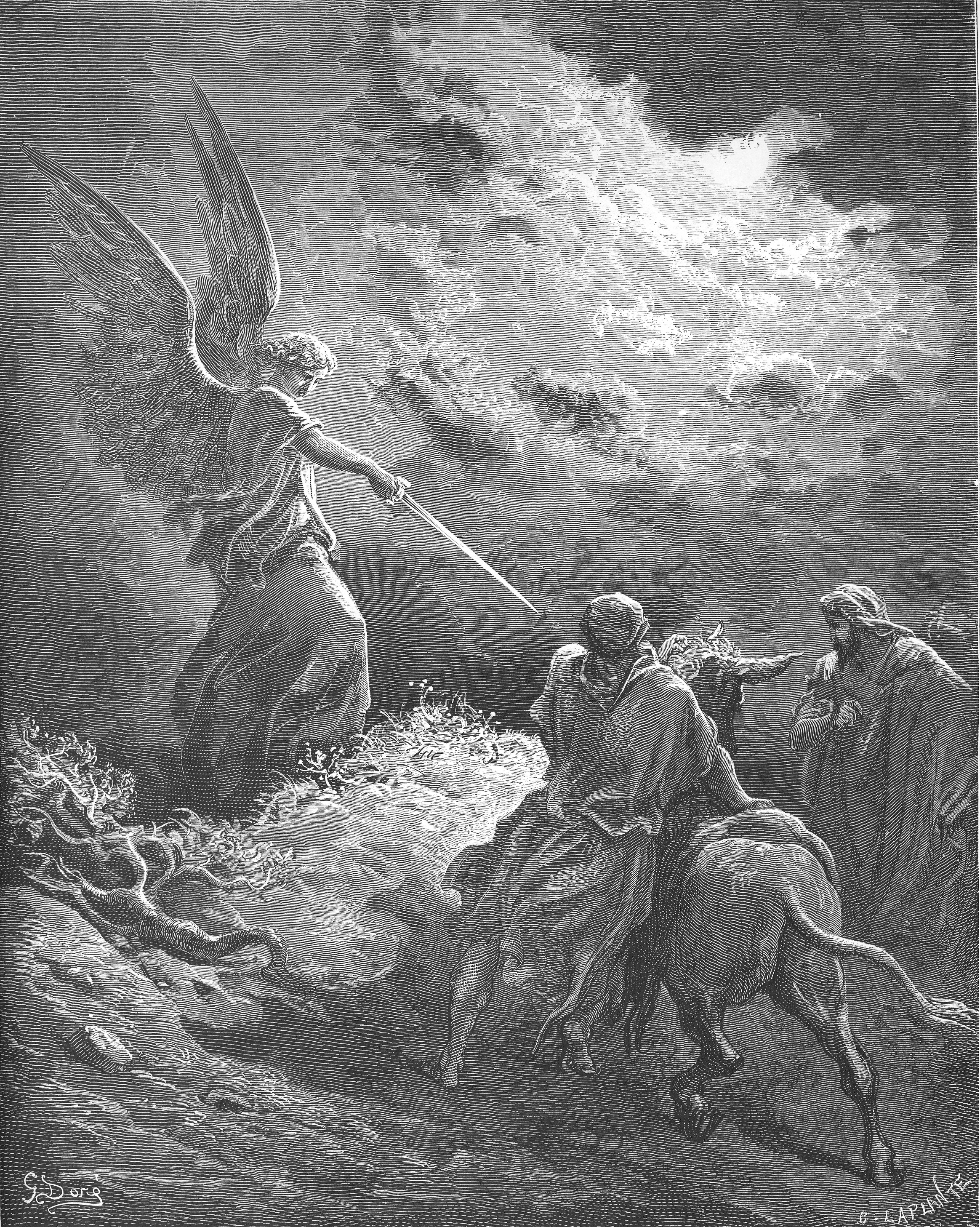

“Now Balaam saw that it pleased the Lord to bless Israel, so he did not go, as at other times, to look for omens, but set his face towards the wilderness. Balaam looked up and saw Israel camping tribe by tribe. Then the spirit of God [ruach Elohim] came upon him, and he uttered his oracle…” (Num. 24:1-3), and proceeded to bless Israel (24:3-10). What is unexpected about the divine spirit’s alighting on Balaam is that he is not an Israelite (22:4-5). Further, he is not only a pagan but a diviner (22:7), one who had been hired by Balak, a Moabite king, to curse Israel in anticipation of its invasion of his country. As recorded in Numbers 22-24, Balaam eventually pronounced four oracles that amounted to four blessings upon Israel, all despite Balak’s provision of multiple occasions for Balaam to thwart, through his sorcery, the Israelite menace.

This Balaam episode in Israel’s history is extremely complicated, but our questions concern the missiological implications of this work of the divine spirit. One set of implications perpetuated by the biblical traditions is that it is only through Elohim’s intervention that the curses intended upon Israel were turned into blessing. Balaam’s legacy was associated more so with one clause (31:16; cf. Rev. 2:14) indicating he advised Moabite and Midianite women to seduce Israelite men – which resulted in a massive plague that claimed 24,000 Israelite lives (Num. 25) – than with the three chapters recounting his blessing rather than cursing Israel. In fact, of the oracles of blessing spoken by Balaam, it is repeatedly said in the rest of the Hebrew Scriptures that, “the Lord your God refused to heed Balaam; the Lord your God turned the curse into a blessing for you” (Deut. 23:4-5; cf. Josh. 24:10, Neh. 13:2). What might be understood here is not only that the latter oracles were explicitly mentioned as brought about by the spirit of Yahweh, but also that all of the blessings were given by Yahweh through Balaam (23:5, 16). So God brought about blessing from all that Balaam meant for evil, and for the latter, the Israelites eventually “put to the sword Balaam son of Beor, who practised divination” (Josh. 13:22; cf. Num. 31:8). Applied more broadly missiologically, then, the redemption of the nations can only happen, if one wills, through Yahweh’s direct and protective intervention. Human activity, no matter how well intentioned, cannot achieve such; instead, even the goodwill of pagans ultimately leads only to sin and destruction. Even if there is a general sense in which such a stance is true, this perspective ignores how the text of Numbers 22-24 actually describes Balaam’s actions and attitudes.

Attentiveness to the Balak and Balaam narrative suggests instead that the divine spirit is surely capable of working together with those outside the community of faith, even with pagan sorcerers. Balaam’s response to Balak and his elders from the beginning was to defer to Yahweh (Num. 22:8, 12, 13), who he referred to as “the Lord my God” (22:18). Although Yahweh initially prohibited Balaam from responding to Balak’s offer (22:12), he was later advised: “go with them; but do only what I tell you to do” (22:20; 22:35). From all appearances, Balaam heeded Yahweh’s admonition, telling Balak no less than four times, “The word God puts in my mouth, that is what I must say” (22:38b; cf. 23:3, 26, 24:13). So whatever Balak devised or desired, Balaam responded contrarily (cf. Mic. 6:5). From this perspective, the spirit of Yahweh comes upon a vessel who had not only shown the desire to cooperate with but was fully intending to please the God of Israel. This point should not be lost even if pagan vessels of Yahweh are no less immune to also working against divine purposes in the big scheme of things.

Although the author of the 2 Peter speaks of Balaam’s “madness” and identifies him as one “who loved the wages of doing wrong” (2 Pet. 2:15-16; cf. Jude 11), there are further pneumatological – and by extension, missiological – connections that are worth exploring from this text. Not only does the second Petrine letter earlier insist that, “no prophecy ever came by human will, but men and women moved by the Holy Spirit spoke from God” (2 Pet. 1:21), but it also records that God’s prophetic messages are designed to accomplish divine purposes in anticipation of and “until the day dawns and the morning star rises in your hearts” (1:19). By extension, then, despite “the prophet’s madness” (2:16b), the presence of the divine breath guaranteed the achievement of God’s resolutions. More precisely, under the inspiration of the ruach Elohim, Balaam foretold, “a star shall come out of Jacob” (Num. 24:17), thus initiating the “morning star” notion found variously in the biblical tradition, including that in the Petrine castigating Balaam. In short, whatever might have been Balaam’s motivations and however his heritage might be interpreted, there is no minimizing his prophesying under the oversight of the spirit of Yahweh.Extended missiologically, then, such an emphasis is consistent with the search for signs of the divine spirit’s presence and activity even in pagan cultural realities that might perhaps find final fulfillment in the person and work of Christ, the spirit-anointed one.

It is important to emphasize how impossible it is “to know precisely the nature of the experience expressed by the words ‘the spirit of God came upon him’” (Timothy R. Ashley, The Book of Numbers [Eerdmans, 1993], 487, italics Ashley’s). Yet this much is clear: that the divine spirit appears in this text at a liminal space and time in Israel’s historical self-understanding, at the precipice of their entry into the promised land of Canaan, but yet without any guarantees that they would so complete their sojourn. And it is precisely amidst this precarious betwixt-and-betweeness that they find themselves assailed not only from without (in the immediate scenario by the Moabites under Balak’s leadership) but also from within (through the seductions of the Midianite women). If Israel is here thereby vulnerable on every side and even unsure of her survival, much less her mission, then what we are given here is, in effect, a spirit-prompted view of Israel from the perspective of the nations that Israel is attempting to overcome on the one hand but also yet having to bear witness to on the other hand. Balak’s fears provoked strategic counter-resistance, but Balaam’s prophecies, inspired by the divine breath, enables Israel to understand herself and her mission through a pagan mirror.

Missiologically, then, the Balaam narrative invites consideration of how the mission of God might be illuminated from the perspective of the nations. Those who would bear witness to the God of Israel might even find their testimonies refracted through the witness of others. This may not happen as often as we might like, but if the divine breath can speak through not only a pagan but also his animal (Num. 22:22-30), then we ought never to be presumptive that the nations to whom we are called might not also speak back to us the voice of God.

Amos Yong came to Fuller Seminary in July 2014 from Regent University School of Divinity, where he taught for nine years, serving most recently as J. Rodman Williams Professor of Theology and dean. Prior to that he was on the faculty at Bethel University in St. Paul, Bethany College of the Assemblies of God, and served as a pastor and worked in Social and Health Services in Vancouver, Washington. Yong’s scholarship has been foundational in Pentecostal theology, interacting with both traditional theological traditions and contemporary contextual theologies—dealing with such themes as the theologies of Christian-Buddhist dialogue, of disability, of hospitality, and of the mission of God. He has authored or edited over 30 volumes.

Follow Fuller Seminary on Twitter at @fullerseminary.