Still more things I’ve picked up from Kenneth L. Woodward’s Getting Religion: Faith, Culture, and Politics from the Age of Eisenhower to the Era of Obama. (See my earlier posts on Woodward’s book here and here and here.)

After the disillusionment with “the secular city,” liberal theology turned to a new frontier. It was the Sixties. Lucy was in the Sky with Diamonds. The Maharishi was on television. And in the academic world new frontiers of psychology were apparently opening up.

Liberal theology went “experiential.” This, according to Woodward, “was the antithesis” of the social gospel “and reflected disillusionment with protest politics and social reform. What mattered was transformation of self rather than of society; myth and metaphysics rather than morality; expanded (or altered or higher) consciousness rather than appeals to conscience” (p. 256).

It seemed now as if “humanistic psychology” with its encounter groups, touchy-feely exercises, and self-affirmations was tailor made to take the place of traditional religion. Here was a salvation that could bring personal wholeness, that could solve people’s emotional problems better than pastoral counseling, that could alter reality better than prayer, that could liberate the self better than the gospel. And it’s all scientific, and so intellectually respectable and modern.

But Woodward documents how the humanistic psychology movement, with their theological hangers-on, soon degenerated into moral depravity, New Age silliness, and out-and-out charlatanism.

We read about how liberal theologians fell for Werner Ehrhard and “est,” that mass meeting in an auditorium where he yells at you and doesn’t let you go to the bathroom until you “get it.” There is Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, who started with legitimate study of the acceptance of death but who ended up trying to contact dead people with mediums and seances. There are the Esalen retreats and turn into sex and drug orgies.

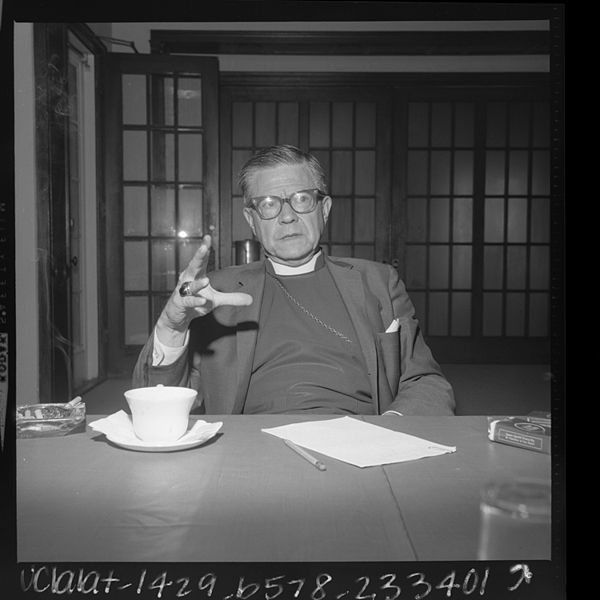

Woodward gives us a profile of the exemplar of this phase of liberal theology gone mad: Bishop James Pike, who was retained as a bishop in the Episcopal church even as he rejected pretty much every tenet of Christianity. That was his secular city phase. But then he went all in with the glorification of the self. His untrammeled sexual appetite destroyed two marriages and led to the suicide of a mistress. When his son killed himself, Bishop Pike tried to contact him via spiritism and the occult. Bishop Pike couldn’t believe in the Holy Ghost, but he came to believe in every other kind of ghost. He went to the Holy Land in an effort to form a psychic bond with Jesus, but he got lost in the desert and was found dead of exposure.

And thus goes another theological trend, which was merely another form of unbelief, though sanctioned by a church. Once again, heresy, seemingly so formidable, becomes a joke.

Photograph of Bishop James A. Pike, Creative Commons via Wikipedia