In my previous posts on Mark Mattes’s new book Martin Luther’s Theology of Beauty, we first discussed how Luther counters the usual understanding of beauty as “perfection” with the theology of the Cross. Next we discussed how Luther, in rejecting Platonism, makes possible a high view of matter, the senses, and emotions. Now we will discuss Luther’s perspective on music and art, including the positive value he finds in aesthetic pleasure.

Platonism manifests itself in two seemingly very different extremes: rejecting art altogether or exalting art as a manifestation of transcendent reality. Some Platonists reject matter, the senses, and emotions–the material that art works with–as being of inferior value to ideals, the spiritual realm, and reason. Other Platonists believe that a work of art is a bridge to the ideal, transcendental, spiritual realm that breaks into our benighted realm and leads us upwards. Neither view accepts the work of art in its own terms as an aesthetic object that conveys aesthetic pleasure.

In Christianity, we see the Platonic influence in both the iconoclasts, who destroy images, and the iconophiles, who venerate them. Luther offers a different perspective altogether.

The Reformed tradition has rejected the use of visual art in church and in worship services. (Mattes calls those who hold this view “aniconocists” rather than “iconoclasts,” since few Christians today are interested in destroying images, as “iconoclasts” denotes. They just don’t use them.) The major reason is their fear of committing idolatry. As Michael Lockwood has shown, the Reformed define idolatry in terms of physicality. An idol is any physical representation or manifestation of a deity. Thus, Reformed theologians consider the Lutheran teaching that Christ is present in the bread and wine of Holy Communion to be idolatry.

Lutherans, on the other hand, define idolatry as any kind of humanly-constructed deity, as opposed to the God who reveals Himself in Scripture. Thus, the deities of other religions are idols, even when–as in Islam–they do not take physical form. The human heart makes less formal kinds of idols, as when we put our faith in ourselves or our nation or our self-devised belief systems, thus turning them into our gods. This is one reason why Lutherans are so preoccupied with having their doctrine right.

But the iconophiles, for whom particular works of art are works of devotion, do not love the images for their own sake. As C. S. Lewis has observed in An Experiment in Criticism, the Christian who prays with the help of an icon is “using” the work of art apart from its aesthetic dimension. It doesn’t matter whether the work is ill-formed or a masterpiece. The aesthetic dimension, the nature of the work “as art,” has nothing to do with the work as a devotional object thought to be a “window” into mystical reality.

Luther’s appreciation of music is well-known, from his own outstanding musical compositions to his legacy of congregational singing. Luther placed music as second only to theology in its spiritual benefits. Mattes shows that Luther followed a new late-medieval understanding of music that emphasized not so much its cosmological symbolism as its affective dimension. That is, Luther shared the new interest in the pleasure that music can bring. Music drives away Satan, Luther believed, because it calms the mind and soothes the emotions.

What St. Augustine felt guilty about–feeling pleasure from church music–Luther sees as the very element that makes it spiritually helpful!

Luther was thus treating music as art and valuing the aesthetic pleasure that it can bring. Luther valued the aesthetic form of music, which he believed embodied both order and freedom. This finds its expression stylistically in the polyphony of Renaissance music, in which the various instruments and voices are all doing different things while harmonizing into a whole. Mattes goes on to show how, for Luther, this kind of music corresponds to his theology of “the polyphonic Christian life.”

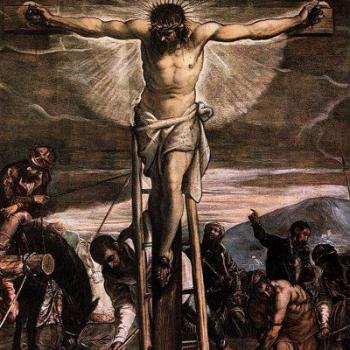

As for visual images, Luther came out of hiding at Wartburg Castle precisely to put down the iconoclastic riots at Wittenberg. He would remove from churches art that pointed away from Christ–to Mary apart from her role as Christ’s mother, to the saints, to devotional reliquaries–but he retained art that pointed to Christ–crucifixes, paintings and statues of Jesus, depictions of the sacraments, Christian symbols. But even pictures of the saints were not to be destroyed, he taught, because they could be helpful in teaching.

In defending his acceptance of visual images against the iconoclasts, Luther pointed out that when we read or hear the Bible we picture images in our minds. If mental images are lawful, he asked, why not visual images made by artists? In thus associating art with the imagination, Luther was making an important connection. Mattes said that for Luther, there is no distinction between word and image. Language itself depends on images. So does reason!

Luther’s sacramental theology–in which the Word is “connected” to physical water, bread, and wine–demonstrates this conviction, as well as his sense that God is hidden in and through all of his physical creation, though not always in a sacramental–that is, Gospel-bearing–way. Also demonstrating this conviction is Luther’s doctrine of the Word, according to which God’s language impacts the human heart by its images of both Law and Gospel.

“For Luther,” says Mattes, “imaging is at the core of what the human heart does, whether concocting idols or honoring God, but it is also how the proclaimed word portrays or pictures Christ primarily as a gift (and secondarily as an example) to believers who thereby receive God’s favor” (p. 133).

In doing so, Luther created a space for art as art and for Christians to take aesthetic pleasure in art. Christians interested in the arts would do well to consult with Luther, and they will find Mattes’s book to be both illuminating and inspiring.

Like the very best books, Martin Luther ‘s Theology of Beauty also is helpful beyond its immediate topic. Mattes also clarifies where Luther stands philosophically and offers an intriguing critique of today’s “radical orthodoxy.” So that calls for yet another post on this book!

Painting, “Christ and the Adulteress,” by Lucas Cranach the Elder [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons