By Isaac Anderson

We are always reasoning from the seen to the unseen. – Emerson

The dissolution of a marriage is holographic, legible from many angles.

This I remind myself two winters ago in January 2012, while eating dinner at a college in western North Carolina with a philosophy professor whose wife of eleven years has recently left him. It’s only our second real conversation, but we’ve hit it off. We sit in a booth in the dining hall, empty except for a couple white-uniformed kitchen staff. Pop music, something forgettable, plays overhead.

He explains: While she was in Bosnia last fall researching for her PhD, she seemed detached, hard to read. A trick of geography, he thought, maybe stress. Until October, when she called to say she’s having an affair with a married man, a man he’s never met. Now she lives in Sarajevo and he lives here.

I, meanwhile, have never met her. I arrived on campus a few weeks ago to teach a nonfiction class for the spring semester, after which I’ll return home to Kansas City. I’m here to listen, I remind myself, not to apportion blame. Blame is none of my business.

Her parents, with whom he speaks often, just came through town on their way to a time-share on the coast. They’re heartbroken, he says, but not resigned. They express hope in their daughter’s eventual return, hope that she’ll wake up one morning to a kind of epiphany, decide her marriage is worth salvaging.

He wants to believe their prediction—he’d move to Bosnia if he thought it would matter. But their optimism has not rubbed off.

What makes them say that? I wonder aloud.

The sun has dropped below the tree line, turning the north-facing windows into dim mirrors. His face is young and angular, pale, recently shaved. He lectured this afternoon on Descartes, wearing a black felt fedora, a white button-down tucked into slacks. The ontological argument; proof of the existence of God. Straight brown hair pushes below the hat brim, looking unwashed. American born, he got his doctorate in Belgium.

In a place like this—the provincial, conservative South—he seems more continental than he actually is.

The conviction of things unseen, the assurance of things hoped for. That’s how the Bible talks about faith, isn’t it? he asks softly.

I nod.

He pushes stale lettuce from one side of his plate to the other. They have faith, but I don’t have faith like them.

He can’t have faith, he says. Not right now, not in her. To have faith in the wrong thing is dangerous.

Last Sunday we attended church together, his Episcopal church, where I remembered that to believe in the divinity of Christ, as I usually do, is not a guarantee that one will be at ease among Christ’s people. Christianity has its subcultures; I’m used to a less formal, less liturgical style of worship. Though it was a beautiful service, I spent two hours juggling the hymnal, the prayer book, the auxiliary hymnal, the service order, trying to guess when to stand, sit, or kneel, when to speak or remain silent, when to sing.

My tie felt like a noose. The priest talked about Christ’s invitation to the disciples: Follow me. I thought of the simplicity of Christ’s words and the religious circus the church has built up around them, all denominations, high and low.

I understand what the philosopher means when he says he doesn’t have faith. I understand the word is multivalent, and that he can stop believing in his marriage—can try to stop—without disavowing belief in a mystical Presence at large in the world. He can close himself to one possibility and stay open to another; he can say No and Yes. He can believe—can try believing—two answers to the same question: Am I alone?

I understand, too, that such a belief is far from easy. Kierkegaard remarked in Fear and Trembling that when considering the life of faith what is most forgotten is the anguish. The Danish philosopher had experienced his own failed romance when breaking off his engagement to Regine Olsen at age twenty-eight, and it seems no coincidence that in his treatise on Abraham he describes the anguish of faith using the metaphor of a lost, impossible love.

To have faith, for Kierkegaard, is to court two beliefs simultaneously, to move in two directions at once, to be torn in half. Faith is a paradox. Concerning the relationship in question, one first possesses infinite resignation: he renounces the claim to the love that is the content of his life; he is reconciled to pain.

But then, unexpectedly, he makes one more movement, more wonderful than anything else, for he says, “I nevertheless believe that I shall get her, namely on the strength of the absurd…”

It’s only a metaphor, of course. One need not renounce romantic love to showcase what Kierkegaard calls faith. Nor must one believe absurdly and against hard evidence that he will reconcile with a woman he still desires.

No, to believe as my friend does, also against hard evidence, simply that there exists in this universe a Being who is aware of him and who still attends to him; a Being who, in my friend’s words, could create something good out of this, even as such language evokes a caped magician pulling a rabbit from a hat, and even as possibility does not equal probability, and though he has no imagination for what this something good might look like and neither do I, to believe in a Being who supposedly has the power and the will to help him negotiate his sadness, but who did not have the power or the will to prevent this sadness in the first place—to believe what we both so often believe—that is absurd enough.

To be continued tomorrow.

Isaac Anderson is an essayist living in Kansas City. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Image, Portland, The Writers Chronicle, Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. His piece “Lord God Bird” (Image, no. 72) was listed as a Notable Essay in Best American Essays, 2013.

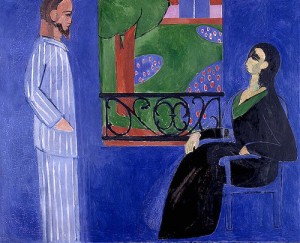

Art Pictured: Henri Matisse, The Conversation, 1908-12, Hermitage Museum