The media may have already lost interest, now breathlessly reporting the latest information about “Jihadi John’s” real identity, but many communities across the United States and around the world are still mourning the loss of three innocent souls, shot in their home in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. The murders of Deah Barakat, Yusor Abu-Salha, and Razan Abu-Salha a few weeks ago have touched us on a visceral and intimate level. I have seen Americans of all races, civil rights and interfaith activists, parents, and college students grieve and mourn together across the United States and abroad.

The media may have already lost interest, now breathlessly reporting the latest information about “Jihadi John’s” real identity, but many communities across the United States and around the world are still mourning the loss of three innocent souls, shot in their home in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. The murders of Deah Barakat, Yusor Abu-Salha, and Razan Abu-Salha a few weeks ago have touched us on a visceral and intimate level. I have seen Americans of all races, civil rights and interfaith activists, parents, and college students grieve and mourn together across the United States and abroad.

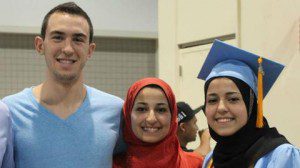

The Chapel Hill shooting struck an especially deep nerve among American Muslims. Many of us feel personally connected to each of the victims, to their families, and to their community, even though most of us had never met them. In the many conversations I’ve had over the last few weeks, one refrain was repeated by mourners across all generational, racial, and economic backgrounds: “I felt like I knew them. This loss is personal.”

Like millions of American Muslims, Deah, Yusor, and Razan expressed their deep religious faith by serving others. They maintained close interracial friendships within their tight-knit Muslim community as well as with their non-Muslims classmates and neighbors. They used social media to organize community service projects, but also to share the light-hearted, profound, and loving moments of their short lives. In other words: they were absolutely typical. Typical young American Muslims, typical college students, typical Millennials. Their community service, social activities and connection with their faith community was so typical, that they literally could have been members of any American Muslim family from Chicago to Chattanooga, from Los Angeles to Long Island.

In a country where an elected official can publicly declare “Islam is a cancer in our nation that needs to be cut out,” without any substantial pushback, the typical American Muslim is the one not portrayed by the media, but exemplified by the Chapel Hill victims: Deah, Yusor, and Razan lived lives that seamlessly integrated their religious faith, cultural heritage and American nationality. They shared the same dreams and aspirations that so many Millennial Muslims do. They laughed, fell in love, Facebooked, danced, applied for competitive academic placements, played sports, and showed their love for God by serving others – like practically every Muslim college student I know.

Yet in last week’s Countering Violent Extremism summit in the nation’s capitol, the U.S. government’s focus was on preventing violent extremism stemming from Muslim communities. Pundits spend air time analyzing why some Western Muslim youth might be susceptible to online recruitment, which is indeed an important step in understanding how to fight radical extremism, but does not tell the full story of the lives of American Muslims.

When I think of online recruits like “Jihadi John,” or the three young Brooklyn men arrested yesterday for plotting to join ISIS, I wrack my brain trying to think of any youth I know from my mosque or local universities whose stories echo those of these disenfranchised, angry young Muslims. I can however think of a hundred young Muslims in mosques, youth groups, and universities across the country, whose stories of service and love for humanity echo those of Deah, Yusor and Razan. By all accounts, these three young people were extraordinary human beings. But as young American Muslims, they were not the exception to the rule.

Still, the statistical outliers in American Muslim communities have become the focus, despite the fact that right-wing extremism has grown exponentially in the US over the last several years.

Days ago a Rhode Island Islamic school was vandalized, with the words, “Now this is a hate crime,” scrawled in an angry orange paint on the doors. A major mosque in Houston was deliberately set on fire by a man who had made anti-Muslim comments in the past. A Muslim family was physically attacked in broad daylight at a Dearborn, Michigan grocery store. In Washington state, a Hindu temple and a nearby middle school were defaced with swastikas and graffiti saying, “Muslims get out.” In Massachusetts, police are investigating a series of threatening letters left at a transit station, proclaiming, “We must kill all Muslims in America.” All of these incidents occurred in the days after the Chapel Hill murders.

Muslim Millennials are not cowed by the rising tide of Islamophobia, whether promoted by politicians pandering to a certain electorate, or replayed by a 24-hour media culture with an insatiable appetite for viewers. But unfortunately, with the Chapel Hill shooting, Islamophobia is coming into our homes and our safe spaces – and the spate of anti-Muslim attacks across the country over the last week has us on edge. Still, we carry the memories of Deah, Yusor, and Razan in our hearts as we uphold their legacy of service. Thousands of mourners came to Chapel Hill to pay their respects at the funeral. Hundreds of vigils have been held across the country and around the world, commemorating the lives of three young people who were murdered, execution-style, in their own home. Imams across the country eulogized them in sermons during Friday prayers. Hundreds of thousands of dollars are being donated on behalf of the three victims toward dental care for Syrian refugees and to feed the homeless in the US.

Lone wolves, feeling disenfranchised and alienated because of imagined slights that challenge their delusions of supremacy are the true faces of domestic terrorism. The majority of American Muslims – the Deahs, Yusors, and Razans – are not. As the CVE Summit wrapped up last week, the lesson may be that to focus on one group – whose hate has been falsely aggrandized by public figures in politics and the media – and not on the statistically-proven other is to try fixing a genuine threat with a flawed perception of reality. And it leaves us no safer.