“Note, today, an instructive, curious spectacle and conflict….Science, testing absolutely all thoughts, all works, has already burst well upon the world—a sun, mounting, most illuminating, most glorious—surely never again to set. But against it, deeply entrenched, holding possession, yet remains…the fossil theology of the mythic-materialistic, superstitious, untaught and credulous, fable-loving, primitive ages of humanity.”

–Walt Whitman

Much ink has been spilt over the divide between religion and science. Whitman, expressing a common view reinvigorated by the New Atheism, frames knowledge as singular, linear, moving from dark to light, from error to illumination. Certainly Science as a cultural institution and a method of critical inquiry may be the most successful of human history in its predictive power, its technological innovation, and its destructive potential.

However, religious knowing like indigenous knowing are not always predicated on empirical knowledge, or sensory data. There are different ways to know something. A scientist can catalogue every aspect of the morphology, life cycle and reproductive strategy of a tree, but still know nothing about it. I found this to be the case in Forestry school, when we would go on long fact filled walks in the gorgeous forests of New England; words like beauty, spirit and wonder simply didn’t come up.

Knowledge is plural, and Science must admit this, not only to right the wrongs of colonialism but to move past the religion vs. science stalemate that is a remnant of the 20th century. A debate atheists “knew” would be over soon, as religion seceded to science.

It is my hope that Contemplative Spirituality, which is becoming more and more popular in a post-religious age, can help bridge the gap between religion and science, not just in holding respectful conversations, but moving toward a synthesis that will help us heal a troubled world.

There are of course many instances of dispute we might use to discuss this idea, but take one in particular: The resurrection of Jesus. Certainly from a scientific perspective the resurrection is improbable. There is no evidence besides the contradictory claims of the New Testament that the man Jesus rose from the dead. In light of this embarrassing state of affairs, one branch of contemporary Christians has entrenched the assertion using the language of Science, while bucking its institutional authority. This plays out by accepting the categories of Science like objective truth, but proposing new ways of understanding history, chemistry, evolutionary biology or geology through the lens of the Bible, for example Creationist theories of a young earth. Fundamentalism developed in relationship to the certainty of modern science. And because of its claims to authoritative truth, coupled with meaning-making it is growing not shrinking.

On the liberal side of the spectrum, it has become fashionable to simply assert a metaphorical or spiritual rationale to the resurrection. The message and Good News of Jesus simply could not be killed by his mortal death, and as his message spread, so too did the idea that he was raised from the dead. The liberal side of the Church is frankly in free fall. Once the relevance of the Bible and Christ have been confined to a metaphorical realm dependent on the truths of Science, its claims lose all power, and one might as well read philosophy, a good novel, or watch the Lord of the Rings trilogy for comfort, entertainment and moral guidance.

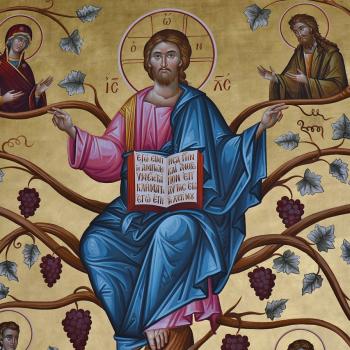

This state of affairs within Christianity mirrors the dualistic framework of contemporary scientistic views of the world: object/subject, traditional/modern and culture/nature. In this ideological straight jacket, we have lost our sense of the mythical as experienced through the mystical. In a time when myths are “busted” truth and knowing are sought only through the senses or verifiable experimentation. However, it is precisely through myth that one is led to the reality of some of our most important truths, whether about trees or resurrected beings.

If Christianity is advanced as a set of verifiable or factual propositions for which Christians must build a case using empirical data, it will die. Science, as a cultural institution has simply won too many of these battles, and presumably will continue to do so.

For this reason I would say that Christianity is not a special kind of history. Christianity is not a special kind of Science. Theology is not a special empirical certainty set up to defiantly contest the claims of history or Science. Christians do not claim to know something science is simply biased against knowing. Christians claim to know something Science cannot know because it is a different kind of knowledge. As the saying goes, religion is mystery not history.

For example, New Atheists like to point out how scientifically inaccurate the Bible is. Written under a completely different cosmos than we live in now, how could the Bible possibly still be relevant? Or, how can Jews and Christians follow a God that seems to petty and vengeful? As many of the monks I have met over the past year have told me, the Bible is not meant to be a scientific, historical or even (primarily) a moral text. It is in essence a story. An account of God’s attempt to love humanity, and humanity’s failure to love God. It is an embodiment of the full range of human emotions, foibles and truths of the human experience. In other words, the Bible is not literally true; it is literarily true.

The power of myth and symbol in the Bible must be rediscovered if Christianity is to survive. However, myth and symbol themselves must also be rediscovered. I am not suggesting for example that Christians simply accept the authority of science as arbiter of truth and embrace the metaphorical power of the Jesus story. Symbol is not the other half of a dualism, it is a door we enter. Truth and knowledge must return to a more pluralistic, lived sense. For example, I do not make claims about whether or not the resurrection is True. However, I do make claims about its reality. By this I do not mean that I came to believe in the truthfulness of the resurrection after accepting it as a proposition of fact. Rather I came to the reality of the resurrection through participation in Christian liturgy and ritual. As one Anglican Priest put it at Christ Church Cathedral in Vancouver, resurrection is a way of being not a way of believing. As a new Catholic ambivalent to many of the truth claims of fundamentalist Christianity, I began to live in a way that was open to the possibility (of resurrection, but also many other things), which then, through symbolic acts, through myth, became real.

Just as trees speak deeply to me even without knowing their taxonomic names, so too do the truths of religion speak to our souls. If Christianity is to survive, it must rediscover the power myth and symbol that transcends the dualisms of modernity.