The male students in my class agreed, “The Bible says that men are more important than women.” In Chinese culture, one never wants to provoke a teacher, but that is exactly what they did that day.

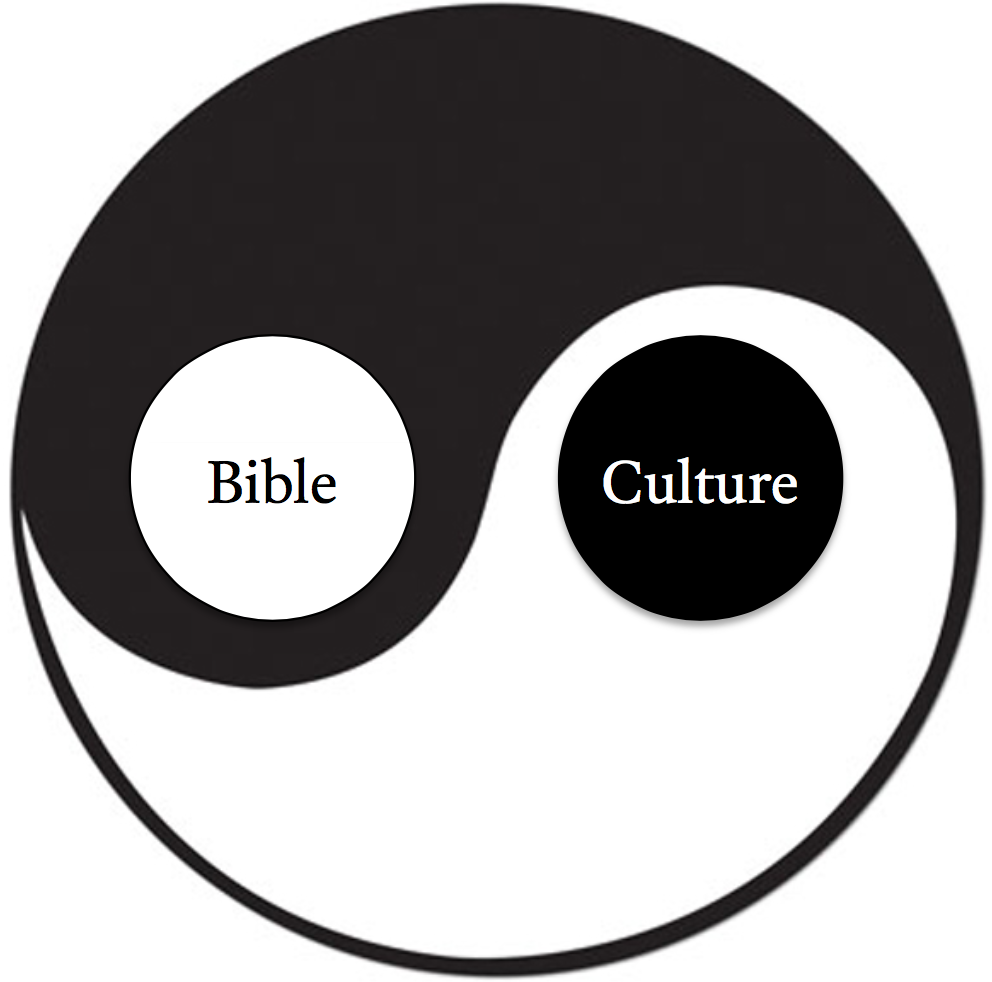

Of all people, my Chinese students should grasp the interdependence of maleness (yang) and femaleness (yin). The yin-yang symbol signifies the balance of contrasts, male-female, dark-light, and perhaps we might add Bible-culture.

When discussing contextualization, evangelicals make a similar mistake as my students. How? By too sharply separating Bible and culture. We ask, “What has priority? The Bible or culture?” In Saving God’s Face, I explain . . .

When discussing contextualization, evangelicals make a similar mistake as my students. How? By too sharply separating Bible and culture. We ask, “What has priority? The Bible or culture?” In Saving God’s Face, I explain . . .

The argument hinges on an order fallacy. To ask whether the Bible or culture has “priority” is unclear. The idea of “priority” can refer either to temporal sequence (i.e. what comes first) or to authoritative rank (i.e. what has authority). According to the fallacy, it is supposed that whatever comes first temporally has greater authority. To the contrary, sequence is not always supreme. For example, in the apologetics . . . one can easily see how reason initially has epistemological authority (over revelation) in its defense of sola scriptura. (SGF, 60)

In other words, the Bible may have ultimate authority (not culture); yet, God reveals himself through human cultures (which already existed). God used cultures to contextualize his self-revelation. The fact that culture is sequentially prior to revelation does not undermine biblical authority.

Afraid of contextualization?

Evangelical “purists” get nervous when they hear talk like this. They are afraid of “eisegesis,” reading culture into the Bible. People get so afraid of cultural syncretism (wherein culture usurps the Bible) that they overlook a more subtle problem––theological syncretism. By this, I refer to the tendency to read the Bible through the lens of our denomination, organization, ministry strategy, etc., and therefore miss so much more of what God reveals in Scripture.

I’ve heard people ask, “Why can’t we just read the Bible and apply it directly to our lives? Why do we have to contextualize? We have the Holy Spirit.” I wish it were that simple.

The way we see the world and thus read Scripture is influenced to some degree by countless cultures and subcultures. We can also add an additional layer—history. We don’t interpret the Bible in a vacuum. Two thousand years of church history shape our assumptions about the Bible and even the questions we ask of certain passages.

We can’t simply claim that the Spirit guards us against cultural influences by illuminating the meaning of a passage to us. First of all, we have to remember that the Holy Spirit guided the biblical writers, who wrote using words, metaphors, and symbols rooted in specific cultures (cf. 2 Pet 1:20, 21).

Second, whose illumination do we trust? One person might say the Spirit gave him illumination that only affirms believer baptism; another might argue that the Spirit revealed that infants could be baptized. The Spirit only teaches finite, culturally bound people with limited perspectives. We mustn’t try to apply the doctrine of illumination abstracted from the facts of history.

Interpreting Biblical Text in Cultural Context

In my new book, One Gospel for All Nations, I not only illustrate the relationship between Bible and culture; I also show why it matters practically for contextualization.

Contextualization fundamentally begins with biblical interpretation. Only then does it concern application and communication. Culture always acts as a filter to what we read. This happens even when we read other ancient works in order to grasp the cultures that influenced the biblical writers.

Contextualization fundamentally begins with biblical interpretation. Only then does it concern application and communication. Culture always acts as a filter to what we read. This happens even when we read other ancient works in order to grasp the cultures that influenced the biblical writers.

Sound biblical exegesis is fundamental to the contextualization process.

We want to understand the Bible’s meaning in its historical and canonical context. We desperately need the humility to acknowledge that we all come to the Bible with a limited viewpoint. We use a cultural lens that invariably causes us to notice some things but overlooks other important ideas. Contextualization occurs whenever we interpret the text from within a cultural context, which is always.

Therefore, we need to ask the practical question, “How do we intentionally account for this dynamic when interpreting the Bible?” This is a key question for everyone, including so-called “professional” Christians like theologians, pastors, and missionaries.

We shouldn’t “throw away” our cultural lens. I don’t suggest replacing a “western” lens for an “eastern” lens. Instead, we need to enlarge our cultural lens so that we might bring a broader human perspective to Scripture. Although I have fundamental differences with many of K. K. Yeo’s conclusions, he is right when he says,

“[A] cross-cultural reading is more objective than a monocultural reading of the biblical text.”

How the Bible ALWAYS Frames the Gospel

We need a practical model for doing contextualization that is both biblically faithful and culturally meaningful. I make such a proposal in One Gospel for all Nations. I begin with an observation that is only seen when we root contextualization in biblical theology (not systematic theology).

Biblical writers always use at least one of three interconnected themes when presenting the gospel. They are creation, covenant, and kingdom.

These themes derive from the grand narrative of Scripture. Without exception, these three themes decisively frame the biblical authors’ gospel presentation. (I demonstrate this key point more fully in One Gospel.) Within this firm framework, one has the flexibility to discuss various other important sub-themes.

A biblically sound model of contextualization is both firm and flexible.

The Bible provides a firm framework. If this framework does not shape our contemporary gospel presentations, we are not preaching the gospel as the biblical writers understood it, (even if we do teach many correct and important doctrinal truths). In addition, we have the flexibility to highlight other biblical themes in accordance with the needs of the surrounding cultural context.

I’d like to hear from you.

- How does your cultural and subcultural background shape the way you see and present the gospel?

- What doctrines and themes tend to get more attention than others?