The intent of James D.G. Dunn’s 3-volume set is to take us from Jesus to the threshold of the Great Church, from Jesus to about 180AD. In volume Dunn examined Jesus Remembered and in the 2d volume he examined the earliest church up to about 70AD (Beginning from Jerusalem). Volume 3, Neither Jew nor Greek (NJNG) examines the period from roughly 70 to 180AD.

The intent of James D.G. Dunn’s 3-volume set is to take us from Jesus to the threshold of the Great Church, from Jesus to about 180AD. In volume Dunn examined Jesus Remembered and in the 2d volume he examined the earliest church up to about 70AD (Beginning from Jerusalem). Volume 3, Neither Jew nor Greek (NJNG) examines the period from roughly 70 to 180AD.

What is noticeable is that he doesn’t let the later creeds or the ecclesiastical history to take control. Rather he wants to follow the path as it developed, not to begin with where it ended. He doesn’t want to ask How did we get the Great Church?, but instead, What happened to Jesus? What happened to Paul, and to Peter, and to John?

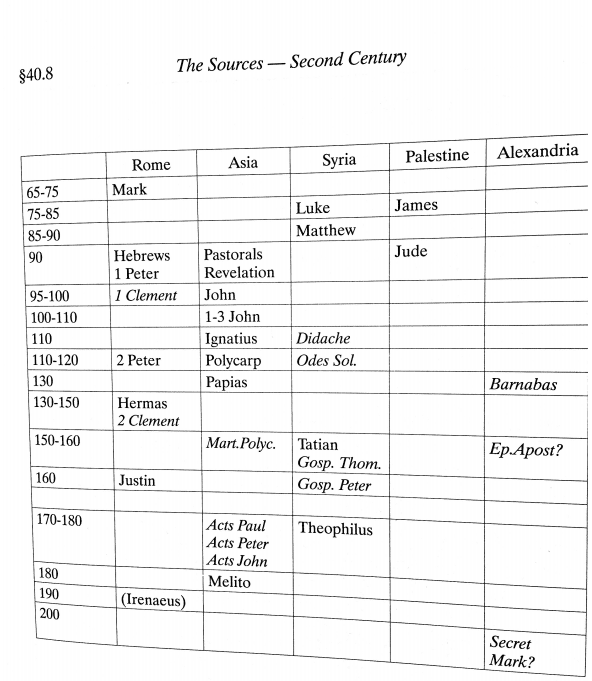

At the bottom of the post is an image of the basic sources and when and where (when he’s more confident) they were written. Including his conclusions on the Gospels themselves.

Today we begin looking at Dunn’s examination of What happened to the Jesus traditions?

Naturally, he begins with the Gospels of the NT — Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John. Before he gets to them, though, he examines “From gospel to Gospel.” Ah, someone who pays attention to the spelling — the term “gospel” means the message about Jesus while the term “Gospel” means one of the Four Gospels in the NT. Dunn begins by examining how we got from gospel to Gospel.

He begins by noting, first, that it was Paul who gave the term to the church mostly and, second, that Paul’s usage was rooted in Isaiah (not in some anti-imperial theme):

The noun ‘gospel, good news’ (euangelion) is one of several terms which Christianity owes to Paul; 60 of its 76 occurrences in the NT appear in the Pauline corpus. We have already noted that Paul’s introduction of this term into Christian vocabulary was unlikely to be the result of his primarily opposing his ‘good news’ to the euangelion (or more likely euangelia) of Caesar, even though Paul was probably aware that such an inference could be drawn. More likely he was influenced by the OT use of for to speak of the bringing of good news, especially of God’s saving deeds, and especially as used by Isaiah [Isa. 40.9; 41.27; 52.7; 60.6; 61.1; similarly Nah. 1.15].

[Joe Modica and I co-edited a book called Jesus is Lord, Caesar is Not, that took on this now very popular idea that “gospel” was framed explicitly and overtly as a subversion of empire and Caesar, and our authors concluded the evidence is being overcooked. We also suggested that this framing of “gospel” today is shaped by leftist politics and that Jesus and Paul are conveniently being colonized to further modern political agendas.]

That much is clear but when did the Jesus tradition become “gospel” and then “Gospel”? The answer is Mark — e.g., Mark 1:1 and 14:9. This term does not appear in Q. Paul, it is clear, often used “gospel” for the saving events of Jesus’ life (death and resurrection), but Dunn makes the case that the Jesus tradition was inherent to the Pauline “gospel.” (Not sure why Dunn doesn’t give far more emphasis to 1 Cor 15.)

He finds support in these considerations: Paul’s use of Isa 61 reflects Jesus’ similar use; telling people about the death and resurrection required at some level for the gospeler to say something about Jesus’ life and teachings; Paul’s allusions to Jesus’ teachings witness to an existing tradition about Jesus in use; tracts about Jesus were in existence; the earliest memories of Jesus — here he goes to Acts 10:34-43 — had a narrative structure to them.

Thus,

In short, if, as seems most probable, a body of Jesus tradition was part of the message which Paul delivered to his converts, part of the foundation on which he sought to build his churches, it most naturally follows that Paul and his converts would have seen such material as at least complementary to the gospel, if not itself integral to the gospel. We need not argue over terms used, but it is most likely that Paul thought of the information about Jesus and the passing on of the teaching of Jesus as integral to the process by which he became father of many new children ‘through the gospel’ (1 Cor. 4.15) (192).

The move from Jesus tradition to gospel then was very early and organic to the early church. From the outset the “gospel” was about the life and teachings and death and resurrection of Jesus, not just a soteriological message.

Mark: Mark uses “gospel” seven times (1:1, 14, 15; 8:35; 10:29; 13:10; 14:9), and it is noteworthy (to Dunn) that both Matthew and Luke drop many of these, and he suggests this is because they knew Mark’s interpretive moves at work here. But for Mark stories about Jesus were part of the gospel. Most notable, though, is that Mark calls his book “gospel” (1:1).

Here is the origin of Jesus tradition to “gospel” and gospel to “Gospel”.

As the Jesus tradition is no longer conceived (if it ever was) as supplementary to the gospel, but as gospel itself, so the writing which contains the Jesus tradition is not to be regarded as merely a container of the gospel, but is here itself becoming the Gospel (195).

And Mark’s Gospel makes it clear that the Gospel is a “passion narrative with an extended introduction” (famous line of Martin Kähler). I would add one further point: the gospel as Gospel entailed just as much telling that story of Jesus as the fulfillment of the story of Israel. Thus, that “fulfillment” motif was inherent from the beginning too.

Matthew and Luke: each takes over Mark’s narrative structure that focused on the Passion narrative. They each used Mark for their own retellings of the story about Jesus. They also used Q.

John. He doesn’t think John knew or used the Synoptic Gospels. For all the differences, the same Gospel format is in use with John. Thus, the Passion narrative suffuses the whole Gospel of John.

Dunn thinks “gospel” became a fixed genre — a Gospel — with Mark setting the agenda at least by the time of the Didache (8:2; 11:3; 15:3-4). There was one gospel and it was known in various forms, that is the Gospel according to Mark.

Sources: