You believe in spanking? Julie Beck:

You believe in spanking? Julie Beck:

Around the world, an average of 60 percent of children receive some kind of physical punishment, according to UNICEF. And the most common form is spanking. In the United States, most people still see spanking as acceptable, though FiveThirtyEight reports that the percentage of people who approve of spanking has gone down, from 84 percent in 1986 to about 70 percent in 2012.“The question of whether parents should spank their children to correct misbehaviors sits at a nexus of arguments from ethical, religious, and human-rights perspectives,” write Elizabeth Gershoff of the University of Texas at Austin, and Andrew Grogan-Kaylor of the University of Michigan, in a new meta-analysisexamining the research on spanking and its effects on children.The researchers raised concerns that previous meta-analyses had defined physical punishment too broadly, including harsher and more abusive behaviors alongside spanking. So for this meta-analysis, they defined spanking as “hitting a child on their buttocks or extremities using an open hand.” They also worried that spanking was only linked to bad outcomes for kids in studies that weren’t methodologically outstanding. It’s hard to study real-world outcomes like this; there are only a few controlled experimental studies in which some mothers spanked their kids and some didn’t, in a laboratory setting. Those were included in this analysis, along with cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, for a total of 75 studies, 39 of which hadn’t been looked at by any previous meta-analyses. Altogether, these studies included data from 160,927 children.The researchers looked at the effect sizes from these studies, to see how strong their results were. There were 111 different effect sizes for 75 studies (some of the studies included more than one result). Of those, 108 found that spanking was linked to poor outcomes. Seventy-eight of the negative results were statistically significant. Only nine results indicated that there could be a benefit to spanking, and only one of those was statistically significant.“Thus, among the 79 statistically significant effect sizes, 99 percent indicated an association between spanking and a detrimental child outcome,” the study reads. Those outcomes were: “low moral internalization, aggression, antisocial behavior, externalizing behavior problems, internalizing behavior problems, mental-health problems, negative parent–child relationships, impaired cognitive ability, low self-esteem, and risk of physical abuse from parents.”

Thomas Daigle and Leicester City FC:

For hockey fans, it’s the equivalent of an AHL team making it to the Stanley Cup finals. Bookmakers said it was as likely as the discovery of the Loch Ness Monster. Even the staunchest supporters of Leicester City FC didn’t believe the team would make it this far.

With a win this Sunday, Leicester would clinch the English Premier League title.

“At the start of the season, I would have been happy with 17th place,” said longtime fan Charlie Cranston. “That would have been a good season for us.”

After spending much of the past decade in lower leagues, Leicester now sits atop English Premier League soccer with three matches left to play. The Foxes, as they’re known, stand a real chance of winning it all for the first time in the club’s 132-year history.

Not only does the team represent a city smaller than Halifax, Leicester’s payroll is only a fraction of those of internationally renowned clubs such as Chelsea and Arsenal. Manchester United is expected to become the first English team to earn £500 million — about $910 million Cdn — in one season, despite sitting four spots behind lowly Leicester.

“Money has shaped entirely the European game until now,” said John Williams, a senior lecturer in sociology at the University of Leicester who specializes in soccer.

“It’s unheard of, really, for a club of Leicester’s size to win the league title, so completely out of the blue,” Williams said.

The feat was so implausible that, at the start of the season, bookmakers gave Leicester 5,000-1 odds of winning it all.

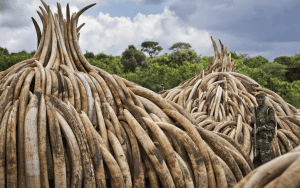

Tusks from more than 6,000 illegally killed elephants will be burned in Kenya on Saturday, the biggest ever destruction of an ivory stockpile and the most striking symbol yet of the plight of one of nature’s last great beasts.

The ceremonial burning in Nairobi national park at noon will be attended by Kenya’s president, Uhuru Kenyatta, heads of state including Ali Bongo Ondimba of Gabon and Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, high-ranking United Nations and US officials, and charities. A wide network of conservation groups around the world have sent messages applauding the work.

On Friday, Kenyatta said Kenya would seek a “total ban on the trade in elephant ivory” at an international wildlife trade meeting in South Africa this September. “The future of the African elephant and rhino is far from secure so long as demand for their products continues to exist,” he said.

On Saturday about 105 tonnes of elephant ivory and 1.5 tonnes of rhino horn will burn in 11 large pyres, about seven times the amount previously burned in a single event. The bonfire, so big it will take about four hours to burn completely, highlights the continuing crisis in elephant populations. About 30,000 to 50,000 elephants a year were killed from 2008 to 2013 alone, according to the Born Free Foundation, and the rate of killing is outstripping the rate of births in Africa.

Prior to the burning, as much scientific and educational information as possible has been extracted, and Kenya will be left with about 20 tonnes of ivory that are still going through the legal process.

Ronnie Wood, the Rolling Stone and patron of the Tusk charity, was among celebrities speaking out ahead of the burn: “It makes me so sad to think that in another 15 years or so elephants, rhinos and even lions could have disappeared from the wild, denying our children the experience of knowing and loving them. We just cannot allow that to happen.”

Let’s pretend you are…, by Courtney E. Martin:

Let’s pretend, for a moment, that you are a 22-year-old college student in Kampala, Uganda. You’re sitting in class and discreetly scrolling through Facebook on your phone. You see that there has been another mass shooting in the US, this time in a place called San Bernardino. You’ve never heard of it. You’ve never been to the US. But you’ve certainly heard a lot about the gun violence there. It seems like a new mass shooting happens every week.

You wonder if you could go there and get stricter gun legislation passed. You’d be a hero to the American people, a problem-solver, a lifesaver. How hard could it be? Maybe there’s a fellowship for high-minded people like you to go to the US after college and train as social entrepreneurs. You could start the nonprofit organisation that ends mass shootings, maybe even win a humanitarian award by the time you are 30.

Sound hopelessly naive? Maybe even a little deluded? It is. And yet, it’s not much different from how too many Americans think about social change in the global south.

If you asked a 22-year-old American about gun control in this country, she would probably tell you that it’s a lot more complicated than taking some workshops on social entrepreneurship and starting a nonprofit. She might tell her counterpart from Kampala about the intractable nature of the legislative branch, the long history of gun culture in this country and its passionate defenders, the complexity of mental illness and its treatment. She would perhaps mention the added complication of agitating for change as an outsider.

But if you ask that same 22-year-old American about some of the most pressing problems in a place like Uganda — rural hunger or girls’ secondary education or homophobia — she might see them as solvable. Maybe even easily solvable.

I’ve begun to think about this trend as the reductive seduction of other people’s problems. It’s not malicious. In many ways, it’s psychologically defensible; we don’t know what we don’t know.

If you’re young, privileged, and interested in creating a life of meaning, of course you’d be attracted to solving problems that seem urgent and readily solvable. Of course you’d want to apply for prestigious fellowships that mark you as an ambitious altruist among your peers. Of course you’d want to fly on planes to exotic locations with, importantly, exotic problems.

Great story of the week, by Colby Itkowitz:

The fundraising page she’d created online more than a month ago sat stubbornly at $60. Meanwhile, the family scrimped and saved. They traded their nicer phones for cheaper prepaid ones. Donnie Davis stopped getting her hair and nails done. Everything that didn’t go to the bills was set aside for adoption fees.

Then they went through their belongings, getting rid of anything they didn’t need. They’d sell it all in a yard sale. “Even if I sell this for just a quarter, we’re a quarter closer,” Davis, 40, said she’d reasoned over an item.

Her son, Tristan Jacobson, a shy 9-year-old who loves math and basketball, wanted to help, too. So Davis suggested he set up a lemonade stand during the sale.

Tristan has been under Davis’s legal guardianship since he was 5, she said, but they’ve never had the discretionary income to pay the costs of legally adopting him.

“To me and my husband he’s already our son, we’ve raised him,” Davis said. “It gives him the assurance that he has his family that he will always be with us.”

Word got around their community in Springfield, Mo., about Tristan’s upcoming lemonade business to fund his adoption, and a local newspaper did a story about it. So did a few of the local television stations and radio stations.

[Hundreds of Flint children don’t fear washing their hands, thanks to one 7-year-old boy]

Over the weekend, people showed up at their home in droves. One couple drove 2 1/2 hours, Davis said. Another man was driving from California to Chicago and heard the story on the radio and detoured to get a bottle of Tristan’s lemonade. They were selling each lemonade for $1. Many people paid $20.

A year ago at this time, Illinois resident TR was flabby and fatigued. The black bear has since lost one-fifth of his body weight and has a new spring in his step. Benny, his bobcat neighbor, lost a good quarter of his weight.

Their secret? Not diet pills or bariatric surgery, but rather those boring things your doctor probably orders: Fewer sweets, more veggies and more movement. Evidently what works for people also works for zoo animals.

TR and Benny are among the denizens of Illinois’s Wildlife Prairie Park who received some bad news last year, according to the Peoria Journal Star: They were too fat. TR weighed 756 pounds; Benny weighed 41. Badgers, cougars, raccoons and other non-roaming animals at the park had also ballooned beyond reasonable proportions.

Unsurprisingly, this happens to captive animals with some frequency. Their conditions — human-provided menus and unnatural environments — are probably to blame.

In 2014, researchers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham reported that 40 percent of African elephants in U.S. zoos were obese and at risk of developing heart disease, arthritis and infertility. Last year, the Copenhagen Zoo said its residents — “basically all of the animals except the birds,” as a spokeswoman put it — had packed on too many pounds. Lucy, a 42-year-old orangutan at the National Zoo in Washington, was deemed 25 to 30 pounds overweight last year, in part because she preferred slacking off to swinging on overhead cables.

Backlash — economic style — at the University of Missouri, by Jillian Kay Melchior:

His prediction proved spot-on. The 7,400 pages of e-mails, obtained exclusively by these two publications, reveal how Mizzou overwhelmingly lost the support of longtime sports fans, donors, and alumni. Parents and grandparents wrote in from around the country declaring that their family members wouldn’t be attending Mizzou after the highly publicized controversy. Some current students talked about leaving.

This passionate backlash doesn’t appear to have been a bluff. Already, freshman enrollment is down 25 percent, leaving a $32 million funding gap and forcing the closure of four dorms. The month after the protests, donations to the athletic department were a mere $191,000 — down 72 percent over the same period a year earlier. Overall fundraising also took a big hit. [HT: CHG]

“It is a principle of music to repeat the theme. Repeat and repeat again as the pace mounts.” William Carlos Williams had it right, in words later set by one of music’s most repetition-obsessed composers, Steve Reich in his The Desert Music.

But it’s not just the minimalists, the likes of Reich or Philip Glass. Repetition is a musical fundamental that connects every culture on Earth. And it’s not just the songs, symphonies or operas we love that are so often built on patterns that repeat – drumbeats, rhythms, melodies, harmonic cycles – it’s also that we love to listen to the same music, the same recording, again and again. And instead of being bored by the fact that we know that particular moment of achingly expressive vibrato is coming up on Billie Holliday’s recording of Summertime; or that the fugue in the Kyrie from Bach’s B-minor Mass is going to resolve in its final bar so radiantly into the major key from the minor; or that, despite our fondest hopes, Violetta is always going to die to those morbidly delicious strains of Verdi’sLa Traviata, our enjoyment increases the more we hear them. Far from diluting our pleasure, repeating them only seems to amplify our involvement in these musical experiences.

It’s an odd phenomenon that has little crossover in other art forms. As Elizabeth Hellmuth Margulis’s work has revealed in On Repeat: How Music Plays the Mind, her book on precisely this phenomenon, it’s certainly not the same with words. If you say a phrase – a collection of words – over and over again it starts to become simply a collection of sounds rather than “meaning” anything. (Gertrude Steinand other avant garde writers made a new kind of literature from this fertile borderland where words are carriers of sound instead of signifiers of meaning.) It’s called “semantic satiation” – that moment when a phrase is overloaded through so much repetition that it slips out of the meaning-processing part of our brains.