Last Wednesday I was on Raise the Horns Radio with Jason Mankey, talking about The Path of Paganism, blogging, the publishing industry, and a bunch of other things. Jason asked me a question I’ve gotten a few times already: “how has being a published author changed you?”

I find that question both amusing and frustrating. On one hand, as a lifelong bibliophile, it’s amazing to hold a real book that I wrote. At the same time, I finished writing The Path of Paganism in December 2015 and I turned in my last edits in August 2016 – I’ve been done with it and on to other things for so long the publication was rather anticlimactic. If becoming a published author has changed me, it’s changed me in small, incremental ways.

But being a published author has changed the way others see me. Or at least, how some others see me. I’m sure long-time blog readers haven’t changed their opinion of me very much. I’ve been almost overwhelmed with invitations for podcasts and public appearances, most of which I’ve been honored to accept and some of which I’ve had to turn down because of scheduling conflicts and limitations on my vacation time. All of a sudden, because there’s a book with my name on it, people who never knew I existed think I’m an expert or something.

It’s hard not to take this personally. I’ve been blogging for almost nine years. I’ve been leading public rituals for fourteen years and teaching in public for ten. But all of a sudden, because I’m a published author, now people are paying attention to me? I didn’t just appear on the Pagan scene in April – I’ve been working on this for a long time.

But it’s not personal – it has nothing to do with me or with the quality of my writing, speaking, and teaching. It has to do with the value our wider society (of which we are all a part, like it or not) places on the written word and especially on published books.

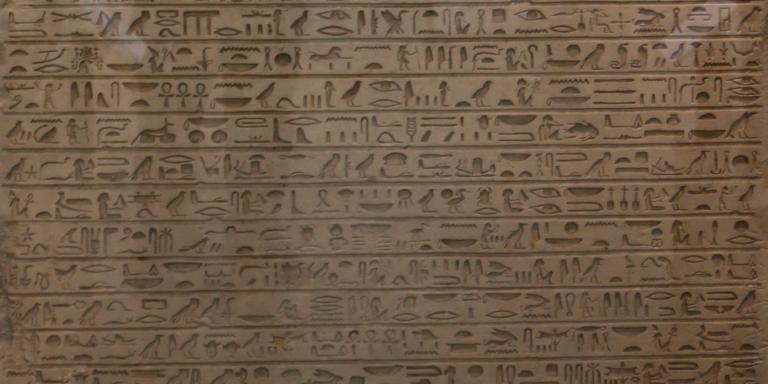

We see this in our common language. Make an arbitrary pronouncement and someone will challenge you with “where is it written?” Talk about a serious commitment and someone will say it’s “written in blood.” Talk about something that can never be changed and we say it’s “carved in stone.” We have a strong bias for the written word.

It’s tempting to blame this on the Protestant belief that all authority comes from the Bible. But bibliolatry is a symptom of a wider phenomenon, not the root cause.

We know from experience that writing things down is more reliable than trying to remember them, thus we have grocery lists and contracts. We’re given textbooks in school and most of what we learn is true, so we learn to trust what we read in books. We know that newspapers have reporters and editors committed to publishing the truth, or at least the truth as they understand it. Seeing something in print gives it credibility.

Only later do we learn that people can and will lie in writing as easily as they lie in speech. History is written by the winners and truly objective textbooks are rare. Some news sources are more interested in promoting their politics than in reporting the truth. And some books are so wrong, so false, so harmful they never should have been published.

And still we defer to the written word.

In the 1999 book The Alphabet Versus The Goddess, Leonard Shlain argued that writing in general and writing with alphabets in particular (as opposed to writing with hieroglyphs or pictograms) is a decidedly left-brain activity, whereas oral and visual communication is more balanced. This emphasis on left-brain activity changed the way humans thought about everything, which he says resulted in abandoning Goddess worship and egalitarian societies for God worship and patriarchy.

On the whole, I found Shlain’s thesis unconvincing. But his foundational argument is correct: “any society acquiring the written word experiences explosive changes.” More relevant to us, writing promotes “linear, sequential, reductionist, and abstract thinking.” Writing brought great benefits to cultures that embraced it, but those benefits came with a price: the loss of “a holistic, simultaneous, synthetic, and concrete view of the world.”

It is ironic that many of us in the Pagan community are using writing to promote a holistic, simultaneous, synthetic, and concrete worldview.

One of the themes of The Path of Paganism is examining our unstated assumptions – the primacy of the written word definitely belongs on that list. So does our preference for linear, sequential, reductionist, and abstract thinking.

That kind of thinking – while useful in its place – causes us to devalue our religious experiences. It causes us to deconstruct them into little pieces that can be safely catalogued according to accepted science and metaphysics. It causes us to try to fit them into abstract models that bear little resemblance to the world we actually live in. And it ends with us writing about them using language ordinary people can’t follow and convincing ourselves that means we’re intelligent, mature, and sophisticated.

Meanwhile, Wild Gods are calling us to meet them in the forest, in our back yards, and in our bedrooms.

On the radio show, Jason asked if “Pagan” is still a useful term. I say it is. The Big Tent of Paganism encourages us to work together where we have common interests, and it provides an entry point for new people who don’t yet know if they should be a Wiccan, a Druid, a Kemetic, a ceremonial magician, or something else.

But the religion I practice – that I call ancestral, devotional, ecstatic, oracular, magical, public polytheism – is also pagan, in the original sense of the word. It’s a religion of country dwellers who honor their Gods and ancestors and who do their best to live in harmony with the land and the spirits of the land. It’s a religion where being and doing are at least as important as thinking and believing. It’s a religion where ecstatic experience is valued on its own and not crammed into some psychological or materialist box.

And it’s a religion where the written word is a useful servant, not an arrogant master.

Experiences lead to beliefs, as we interpret what happened and put it into the context of our ideas about the way the world works. Beliefs lead to practices, as we attempt to carry out the instructions we’re given, and as we attempt to make our visions manifest in this world. We use writing to help us organize our thoughts and to communicate our ideas with others. This is a good thing. I’ve been reading and writing since before kindergarten and I’m thankful for the written word.

But if we are to build a religion that is holistic, simultaneous, synthetic, and concrete – if we are to become pagan as well as Pagan – then the primacy of the written word must give way to the primacy of religious experience.