What It’s About: This passage operates on several levels. It’s an institution of a kind of tithing system, in which the first fruits are given to God. But it’s also a recitation of salvation history, giving an account of God’s mercy and provision to the people. In that way, it is somewhat exclusive, as we will discuss below. But, in verse 11, it opens out again, taking into account the “aliens who reside among you” and not simply the people of Israel. So this passage is doing a lot of work in the area of communal identity (who are we, how did we get here?) and communal obligation (what do we owe to the God who brought us here?), but it’s also bearing in mind that concern for the Other that is so characteristic of parts of the Hebrew Bible.

What It’s Really About: It’s always important, when reading Deuteronomy, to remember its context. As its name suggests (deutero=second; nomos=law), Deuteronomy is a reassertion and a reinterpretation of the tradition found elsewhere in the Torah. There are differing theories about it, but Deuteronomy can probably be identified with the period of Josiah, a reform-minded king of Judah in the 600s BCE. Deuteronomy might have been written or edited during his time, but no matter when it was written it seems to have been a kind of constitutional document for that period, describing the way the Israelites were reinterpreting their religion for a new time and place. It’s a kind of revival, wrapped up in a book of law. So this passage can be read that way: as a reassertion of old ideas, but in a new time and place, and a re-telling of an old story, but with an eye to changed circumstances. You can see that in verses 2 and 3–veiled references to Jerusalem and the priesthood there, which was a central part of Josiah’s reform. The centralization of power and worship in Jerusalem was an innovation of that time.

What It’s Not About: As with any narrative of conquest, this one leaves out some important characters: the ones conquered. That line about “the land that the Lord your God is giving you as an inheritance to possess” hides some important realities. The land was populated beforehand, of course, with people who did not consent to losing their land. Scholars disagree on how the Israelites got into Canaan; it might have been more like Joshua’s account, with military conquest and bloodshed, or it might have been more like Judges’ account, with more gradual intermingling and change. But the story that this passage is telling is more like Joshua’s, and it’s important to read those kinds of things carefully. Something similar happened in North America, of course. The liberating narrative of Exodus always has to be read in light of the destructive (and even genocidal) discourse of conquest. You can’t affirm one without taking account of the other.

Maybe You Should Think About: What does the concept of the first fruits mean? Most of us no longer live in agricultural contexts. What is a “fruit,” then, and what counts as “first?”

What It’s About: This is part of Paul’s careful but opaque argument in his letter to the Romans, which is the closest he ever comes to explaining himself. All of Paul’s letters are…well…letters, and not theological treatises. We cannot, then, expect them to work like theological treatises, answering every question. But in Romans, Paul comes closer than he does elsewhere to laying out his thought in a systematic kind of way. What we see in this section of Romans, then, is Paul trying very hard to communicate his notion of what Jesus has meant. For Paul, it’s connected to that part of verse 11 of the Deuteronomy text above; it’s an expansion of God’s concern outside of the people of Israel. Paul thinks that Jesus’ life and death means an opening up of the possibilities of salvation. But the nature of that salvation might be a little unfamiliar to us.

What It’s Really About: Verses 9 and 10 can mislead us a little bit. We have to recognize that Paul is using a pretty different language of salvation than we are. Paul uses language like “confess” and “believe,” which map pretty readily onto 21st century Christian notions of salvation. But Paul doesn’t really operate with an individual notion of salvation. You can see this in the way he works: he plants a church in this city and then in that one, working his way westward. Later on in his letter to the Romans, he asks for their help in getting to his ultimate goal: Spain. Paul wants to get to Spain because he thinks it’s the end of the world, and once he has preached to the end of the world, his job will have been done. Paul has no notion of retail conversion–one person at a time. Instead, he thinks of the world in terms of provinces, ethnic groups, and large swaths of geography. He just needs to preach to each part of the world, each kind of people, to fulfill his job. Salvation is strikingly communal for Paul; the individual’s response is almost incidental to this. He needs outposts of belief, and that’s what he’s after. That’s why he can say that there is no distinction between Jews and Gentiles; in this new thing God was doing through Jesus, the mission had expanded to include the whole world. That called for wholesale evangelism, so that God’s wholesale salvation could take place.

What It’s Not About: Paul was Jewish, and he remained so, even as he came to understand that Jesus was the messiah he had been waiting for. Any reading of Paul that is anti-Jewish, then, is illegitimate, and this passage underscores that. Verse 12 returns to that impulse of Deuteronomy, to say that the Lord is Lord of all.

Maybe You Should Think About: Romans is about Paul trying to make sense of Jesus’ life and death, given his time and place. Given our time and place, what sense can we make of it? The season of Lent is really about that–about making meaning out of Jesus. Our meaning might not be the same as Paul’s meaning, but we bear the same responsibility to make meaning nonetheless. How does our time and place help us to interpret what Jesus has meant?

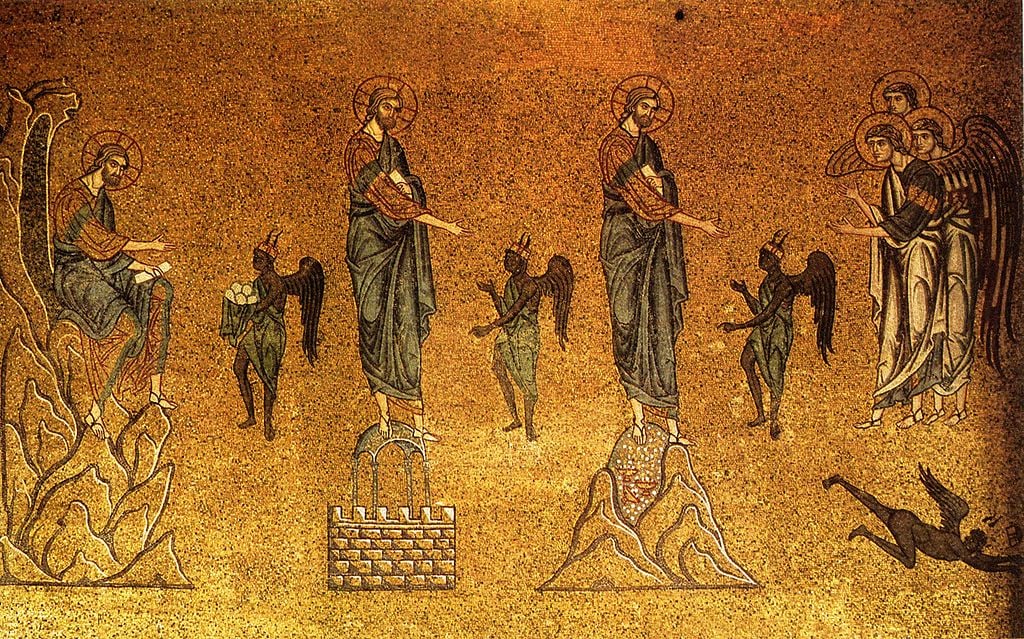

What It’s About: This is the story of Jesus’ temptation in the desert, where “the devil” (who isn’t named) tempts him. This story is common to the synoptic tradition with a few changes across the gospels (note how Mark says the Spirit “drove” Jesus out, while Matthew and Luke say the Spirit “led” Jesus). In every case it follows directly after the baptism, which makes for an interesting theological question: why are baptism and temptation so tightly linked?

What It’s Really About: The New Testament–and Jesus, for that matter–came along at a time when things were in flux with regard to semi-divine beings like angels and demons. The New Testament period coincides with a period of Judaism that saw the development of traditions about Satan. In the Hebrew Bible, Satan rarely shows up, but when he does he is kind of a part of God’s staff (see Job, for example). But by the time of the New Testament, Satan had come to stand in for the personification of evil, with his own nearly-God-like powers. It’s interesting to see how the gospels use (or do not use) Satan in different contexts, then. Why is this “the devil” and not a proper name? Is there any significance to it? And it’s particularly perplexing when Mark (from whom Luke was presumably working) uses the word “Satan.”

What It’s Not About: Names aside, this exchange is about competing power structures. We are to understand that Jesus is choosing between two kinds of power: a positive power that comes from God and a negative kind of power that has to do with selfishness, ambition, and pride. That “the devil” has the negative kind to offer is obvious, but it’s also interesting to notice that the power the devil holds is really mostly relational. With the exception of the “all the kingdoms of the world” one, which the devil apparently has authority over already, the things the devil is tempting Jesus with are things Jesus already possesses. The temptation is the improper use of those things. Even the political power implied in the kingdoms of the world temptation is relational; it has to do with how Jesus wields himself in the world. The temptations, then, are all about how Jesus’ self relates to other selves–to us, even.

Maybe You Should Think About: Lent has morphed into a period of mild self-denial for many Christians in the west. We give up lattes or chocolate or take on exercise. Some of this ascetic impulse can be traced to this story of temptation, in which Jesus’ deprivation seems to weaken his body but strengthen his resolve to resist temptation. But read differently–as a way of describing the possible ways of wielding power–the story of Jesus’ temptation can guide us differently in Lent, to think not about our personal deprivation but the way we orient ourselves toward the world.