The New York Times has christened 2012 as “The Year of the MOOC.” No, “MOOC” has nothing to do with the presidential election or with Hurricane Sandy. “MOOC” means “Massive Open Online Course.” It is the name for a new mode of online education.

MOOCs are exploding in popularity. According to Laura Pappano, writing for the Times:

The paint is barely dry [in the new edX offices], yet edX, the nonprofit start-up from Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has 370,000 students this fall in its first official courses. That’s nothing. Coursera, founded just last January, has reached more than 1.7 million — growing “faster than Facebook,” boasts Andrew Ng, on leave from Stanford to run his for-profit MOOC provider.

“This has caught all of us by surprise,” says David Stavens, who formed a company called Udacity with Sebastian Thrun and Michael Sokolsky after more than 150,000 signed up for Dr. Thrun’s “Introduction to Artificial Intelligence” last fall, starting the revolution that has higher education gasping. A year ago, he marvels, “we were three guys in Sebastian’s living room and now we have 40 employees full time.”

In the past, online education involved enrolling in classes, paying tuition, interacting with faculty online, and getting course credit from a credentialed institution. As Pappano explains, “The MOOC, on the other hand, is usually free, credit-less and, well, massive.”

Yet, the success of the massive online course depends, ironically, on its ability to facilitate intimacy, even face-to-face relationships:

Ray Schroeder, director of the Center for Online Learning, Research and Service at the University of Illinois, Springfield, says three things matter most in online learning: quality of material covered, engagement of the teacher and interaction among students. The first doesn’t seem to be an issue — most professors come from elite campuses, and so far most MOOCs are in technical subjects like computer science and math, with straightforward content. But providing instructor connection and feedback, including student interactions, is trickier.

“What’s frustrating in a MOOC is the instructor is not as available because there are tens of thousands of others in the class,” Dr. Schroeder says. How do you make the massive feel intimate?”

MOOCs do so by facilitating communities among students, both online and embodied:

Because anyone with an Internet connection can enroll, faculty can’t possibly respond to students individually. So the course design — how material is presented and the interactivity — counts for a lot. As do fellow students. Classmates may lean on one another in study groups organized in their towns, in online forums or, the prickly part, for grading work. [emphasis added]

The experience of MOOC students underscores the value of interaction among students. Consider the case of Kimberly Spillman, a software engineer, who enrolled in seven MOOCS but only complete three:

“The ones I have study groups with people, those are the ones I finish,” Ms. Spillman says. She first joined a group for Dr. Thrun’s artificial intelligence course, and then ran one for a Udacity course on building a search engine, organizing Thursday-evening discussions of the week’s material followed by a social hour at a nearby pub. [emphasis added]

Or consider the case of Jacqueline Spiegel, who has a master’s in computer science from Columbia:

While taking “Artificial Intelligence,” she discovered she liked puzzling through assignments in online study groups. . . . Ms. Spiegel befriended women in India and Pakistan through Facebook study groups and started an online group, CompScisters, for women taking science and technology MOOCs.

Testimonial evidence suggests that the massive course works best when there are context for non-massive, intimate community, either online or in person. That’s why Coursera, for example, offers “tools for students to plan ‘meet-ups’ with Courserians in about 1,400 cities worldwide.” There you have it, the massive: 1,400 cities across the globe; and the intimate: face-to-face meet-ups, where students gather for study or socializing.

I find all of this fascinating, though not particularly surprising. Just because we now have the potential to offer online education across the glob, this doesn’t erase the human desire for embodied relationship. Moreover, though certain kinds of learning can be effectively experienced online, other kinds of learning are best facilitated in small groups where people can interact personally. Conversation in community is an essential piece of true learning, not to mention true living.

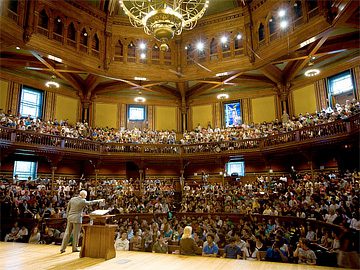

In a sense, the massive/intimate model isn’t particularly new, though the scale of the massive has certainly grown. When I was in college, I took a course called Humanities 103 (or Hum 103), “The Great Age of Athens.” Professor John Finley’s lectures filled Sanders Theater with about 800 students each time the course was offered. But, in addition to the lectures, there were also “sections” in which about 15 students gathered to discuss the course material.

The moral of the story: as we hear more and more about the “massive” online courses, let’s not forget the need for “non-massive” communities. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the success even of the MOOCs depends on the creation of contexts for genuine, intimate relationship.