Attending the Q Conference in Boston this past week, I was reminded that almost any evangelical who wants to leverage their vocation to change the world takes William Wilberforce’s Clapham group as a sort of knights-of-the-round-table paradigm. But few seem to know much about this remarkable group. So as a public service, here’s my . . .

10 Things You Don’t Know about the Clapham Sect

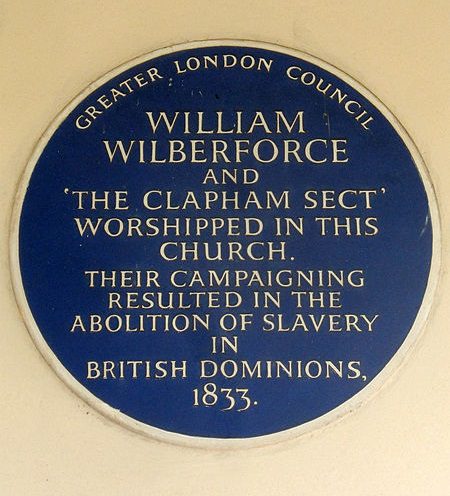

First the basics: The Clapham Sect was a group of aristocratic evangelical Anglicans, prominent in England from about 1790 to 1830, who campaigned for the abolition of slavery (among many other causes) and promoted missionary work at home and abroad. The group centered on the church of John Venn, rector of Clapham in south London.

Today these activists are frequently held up as an example of Christian social-justice reform to be emulated. It’s always good to know a few things about someone you’re going to emulate, so here are 10 things you probably don’t know about the Clapham Sect:

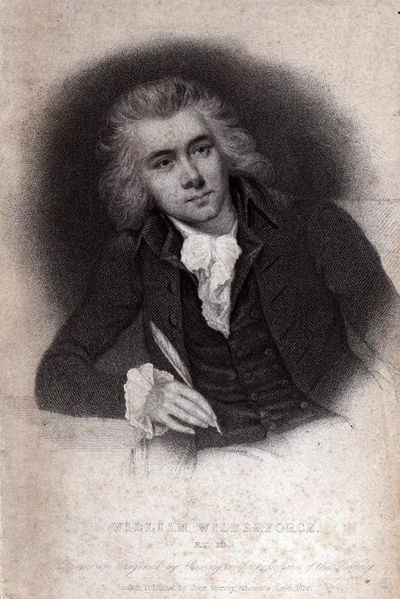

- Aside from the great parliamentarian William Wilberforce and several other MPs, the group also included a

Wilberforce, from Wikimedia. brewer, a banker, several clergymen, the father of the great English historian Thomas Babington Macaulay (Zachary Macaulay), and the great-grandfather of Virginia Woolf (James Stephen). Two of its prominent members were women: the evangelist Katherine Hankey and the writer and philanthropist Hannah More. . (Read more about More in this wonderful new biography of her by Karen Swallow Prior.)

- The term “Clapham Sect” was a later invention by James Stephen in an article of 1844 which celebrated and romanticized the work of these reformers. In their own time the group used no particular name, but they were lampooned by outsiders as “the saints.”

- Though they were of aristocratic background and many of held positions of power and influence, the Clapham group’s involvement in the abolition cause brought significant social stigma on their heads. The English ruling classes viewed abolitionists as radical and dangerous, similar to French revolutionaries of the day.

- Despite this radical reputation, these aristocratic activists proved to have remarkable staying power politically. Wilberforce was one of the five members of the Clapham Sect who held seats in the House of Commons who never lost a parliamentary election.

- Scratch the radical surface and you actually got conservative social thinkers who believed in the preservation of ranks and orders within society and preached philanthropic benevolence from above. Indeed, the Clapham group became the “tip of the spear” of British imperialism in Africa. They founded the first major British colony in Africa, Freetown in Sierra Leone, whose purpose in Thomas Clarkson‘s words was “the abolition of the slave trade, the civilisation of Africa, and the introduction of the gospel there.”

- For the Clapham Sect, the Christianizing of India became a cause second only to abolition. In 1793 the Claphamites tried but failed to alter the charter of the East India Company to allow for missionaries (the company feared that missionaries would try to reform host countries and cause civil unrest that would cut into profits). They were able, though, to get evangelicals, such as Henry Martyn, appointed as East India Company chaplains–who in fact did missionary work as well. In a momentous action in 1813, when the company’s charter came due for renewal, Wilberforce and his friends joined forces with East India Company chairman and director Charles Grant to overturn the vested interests of the company and gained a “Missionary Clause” in the new charter.

- The revision of the East India Company’s charter built on other Claphamite efforts to set the table for British missionaries to go anywhere Britain had an international presence–which in the 19th century meant a lot of the world. We’ve mentioned the founding of Freetown. Even more significant in this vein was the Clapham group’s 1799 founding of the Church Missionary Society for Africa and the East. This was to become one of the most prolific sending agencies of the nineteenth century, the “Great Century” of missions.

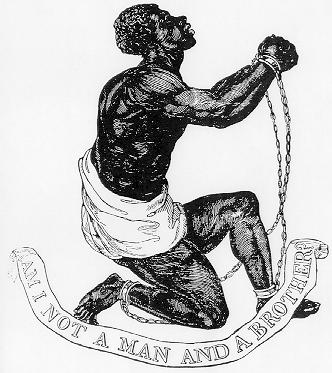

- At the top of the Clapham circle’s agenda—even above missions—was, of course, abolition. Antislavery bills of one

Medallion of the British Anti-Slavery Society, designed by Wedgewood. From Wikimedia. sort or another brought by the Claphamites and their friends were defeated in Parliament for 11 consecutive years before the act abolishing the slave trade was passed in 1807.

- But slavery wasn’t the only social issue that troubled nineteenth-century British Christians, included but not limited to the Clapham Sect. Between 1780 and 1844 Christian activists like the Claphamites founded at least 223 national religious, moral, educational, and philanthropic institutions and societies to alleviate child abuse, poverty, illiteracy, and other social ills. The Clapham group themselves also ran political campaigns to achieve prison reform, prevent cruel sports, and suspend the game laws and the lottery.

- The Claphamites and their genteel reforming brethren had a particular penchant for founding religious and benevolent societies on behalf of impoverished or exploited women. The names of these societies provide a quirky window into the world and concerns of early Victorian evangelicals:

—Forlorn Females Fund of Mercy;

—Maritime Female Penitent Refuge for Poor, Degraded Females;

—Society for Returning Young Women to Their Friends in the Country;

—Friendly Female Society for the Relief of Poor, Infirm, Aged Widows, and Single Women of Good Character Who Have Seen Better Days.

Some items here are borrowed from Richard Pierard, “William Wilberforce and the Abolition of the Slave Trade: Did You Know?” and Bruce Hindmarsh, “A Long Reach: The Clapham Sect’s impact in India—and the world,” from Christian History magazine’s issue #53: William Wilberforce: Fighting the Slave Trade. Other sources: Wikipedia, Encyclopedia Britannica.