I’ve just been informed that the scholar Huston Smith died yesterday, the 30th of December, 2016.

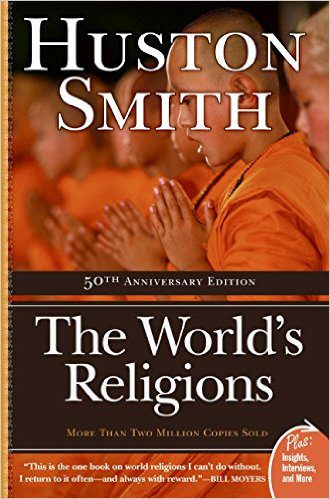

Me, I’m deeply saddened. A great loss to us all. And, for me, an unfortunate coda to the unpleasantness that has been 2016. Professor Smith was the great interpreter of the world’s religions to the general public, his book Religions of Man published in 1958 and later retitled the World’s Religions was two generation’s introduction to the range of religion on our planet. Including me.

As as often is the case with such important works, it turns out there were problems. In fact those very problems are a significant part of my ongoing spiritual journey. I shared a reflection on all this back in May. As it is so directly connected with Professor Huston, I’m sharing it again here, although reworked in the light of both his death and that continuing wrestling with the subject of Religious Perennialism & its close relative Traditionalism.

I first stumbled upon the term Perennialism in Aldous Huxley’s Perennial Philosophy, published three years before I was born. And, for me in my youth searching for an intellectually honest, which meant to me not obviously conflicting with the natural world, this book together with Richard Maurice Bucke’s Cosmic Consciousness, and William James’ Varieties of Religious Experience outlined the general direction for my quest for meaning and purpose in life.

In truth I have a complicated relationship with Perennialism. On the one hand I think it points in the right direction, at least broadly speaking, when it suggests there are common truths that each religion touch. This insight is a big reason I would eventually find myself a Unitarian Universalist. Unitarian Universalism is the great magpie spiritual tradition, open to the possibility of many truths, and of the possibility of a common truth. On the other hand as someone who has actually engaged in some depth several of the world’s major spiritualities, it seems pretty obvious to me that there is not in fact a single mountain we’re all following separate paths up to its summit. It is to me pretty straight forward. There are lots of different mountains.

And with that I’ve come to some other hard conclusions. Some are more useful than others. Which is probably why Zen Buddhism and its disciplines remains the core of my actual interior life. I love the magpie quality of Unitarian Universalism, but, I’ve found I also need a tap root in order to grow deep. For me that has been a reformed Zen Buddhism. I suggest with equal attention to the Zen Buddhism and the “reformed.”

For me the best example of the problems with Perennialism is Huston Smith’s World’s Religions. For many years those of us interested in the World’s Religions found it offered our first glimpses into the richness that are the world spiritualities. For good reason it has continued in print for years, and has all together sold over two million copies. It was a great help to me. I cannot say how grateful I am for Professor Smith’s book.

And. What he doesn’t reveal in the book is that he is a full on Traditionalist, a form of Perennialism that, frankly, I find very attractive, but which has some serious problems. And those problems come from trying to crowbar all the world’s religions together into one lovely jewel of many facets. As I said pretty much up front, this is not so. And so, his book, which is admirable in so many ways, and, again, for which I remain endlessly grateful, when it comes to Buddhism just has a terrible time. Professor Smith believed, I’m quite sure, right down to the soles of his feet that there is a true religion under all religions. I can even go with that, up to a point. But for him that universal thing is a mystical theism. And because of that the chapter on Buddhism is deeply marred by his, to my mind, desperate reach for theistic elements in Buddhism, which exist, but which cannot by any stretch be considered normative, and trying to make them the living current of the tradition.

(I’m also cautioned by how Traditionalism with its focus on holding fast to received traditions has been neatly incorporated into some proto-fascistic political philosophies. Some time later I want to reflect further on this deep problem, but not here…)

At this point in my life the issue is this. I do believe a form of religious perennialism, what I’m calling a naturalistic perennialism. I believe there are currents of religion that are rooted in our biology, and as something natural, also something that people can find within all religions, and actually at the heart of the birthing of all religions. And I hope it would therefore be obvious, this deep current should be available without any religion at all.

There are a number of these currents, some go toward ethics – what I see as an innate sense of the “fair,” a sense that things should be harmonious, what is good for the goose is good for the gander kind of photo-morality confusingly coupled with a deeply held desire to get one up, and with that an inclination to cheat. I believe pretty much all religious ethics arise out of these two things existing in tension.

Rather more important is what is it at the root of the mystical, and by mystical I mean quite narrowly an apprehension of a root to all our individual consciousnesses. For most of the world’s religions this root is seen as God, and as profoundly personal. Hence Professor Smith’s theistic perennialism and more specifically his traditionalism. But Buddhism shows this does not have to be experienced that way. And, for me, points again to our biology. We seem to have within the structures of our brains an ability to see at the same time that we are different and distinct and acting in our own interests, that there is a common place, we exist within an intimacy so profound it is fair to call it one.

I believe the Buddhist explanation, particularly the Zen Buddhist explanation, and more specifically the “modernist” Zen Buddhist explanation (here I’m thinking of an emerging literature led first by Alan Watt’s various writings, but today more aligned with Stephen Batchelor’s Buddhism Without Beliefs, Robert Aitken’s Mind of Clover, and John Tarrant’s the Light Inside the Dark, and perhaps summarized within my own If You’re Lucky, Your Heart Will Break. Throw in the various books by James Austin following his Zen and the Brain what you see is naturalistic, often poetic, of necessity poetic, cut through with a concern for ethics, but always, always grounded in that common human encounter with our fundamental reality – which is both one and many.

And at this moment, at the end of 2016, as we seem drawn into an era of darkness and division, I find myself thinking of Professor Smith and his aspiration to find that which connects. While I feel he made mistakes, that too, is important. For me. For all of us.

I think, I believe, down to the soles of my feet, there are things that connect us, that bind us together. And, in this time we need, desperately, to find those things. And so I’m grateful for Huston Smith’s work, which I feel helped me and many of us, as we’ve sought that deep if elusive thing, our true connections.

So, blessing on you Professor Smith.

And thank you.