If you’ve been reading along in this series of posts about the basics of a Jewish theology, thank you. I’m thinking there will likely be 3 or so more posts in this series after this one.

Let’s turn our attention to Jewish ways of thinking about human nature, morality, and salvation. Again, my thoughts are colored by Reform and Liberal Jewish approaches to these topics, and I’m aware of the diversity of opinion within Jewish thought.

Human Nature

The opening chapters of Genesis, and then the remainder of Torah, seems to indicate that to be human is to be a unique, personal expression of the divine/evolutionary impulse in the world. Metaphorically, we speak of our sharing in this impulse as our sharing in the divine image as persons – we possess an inherent dignity, an ontological value, and a sense of worth that is grounded in our very being and is not merited or earned.

As persons we are unified, self-aware flesh. Our existence melds material and immaterial realities, and that the exact relationship of the mind-soul to the body is a mystery. As persons, we are inherently social, relational, and capable of love – our flourishing is interdependent on others flourishing as well – we are only as whole as the least of our brothers and sisters.

Our wholeness is illusive. Instead of affirming our connection to nature and to others, we too often experience fragmentation, alienation, and separation – the results of egoism and selfish living – treating nature and others as a means to an end and not ends in themselves. We find ourselves living in disequilibrium, harming others, the environment, and ourselves.

Denying our connectedness with nature puts us at risk of peril. If our culture and spirituality is out of balance with nature, everything about our lives is affected; family, workplace, school, and community – all eventually become unbalanced – because neglect or abuse of nature is essentially neglect and abuse of self.

Denying our connectedness to others also risks peril. Humans are inherently social animals – that cannot exist without community; we engender culture with our very being. Interconnected/Interdependent on one another, kindness and social cooperation make sense from a practical, evolutionary point of view – we can only truly thrive when others thrive – this insight is foundational for an integrated spirituality of wholeness.

The way to healing is through restoring healthy relationships, cultivating awareness of our interconnectedness with the ecosystem and the rest of the human family. Humans are capable of transcending ego and living lives of kenotic love in service and harmony with nature and others. We are fully ourselves when we give ourselves away to things that deserve us and reflect/enhance our inherent dignity. Our survival and thriving depends on such right relationships.

Morality

Jews have crafted their moral views through an ongoing conversation with Torah and experience, reason and tradition – much the way some Christian traditions do (in particular, I’m thinking of Orthodoxy, Catholicism, and Anglicanism.)

Jews make their moral decisions and form their views in conversation with the past while living in the present. Neither aspect of the conversation trumps the other.

In a general sense, this manner of moral reasoning has been called the Natural Law tradition. Most Jews wouldn’t be overly familiar with the term, but in essence, it’s the manner of their moral reasoning.

Morality is an integral part of our natural identity. Right human behavior is predicated on human flourishing and empathetic reciprocity, conveyed in the core truth of love your neighbor as yourself – treating others, as we would like to be treated. It is an ancient, universal ethical imperative known through human reason. Judaism, and all religion, is at its best when it reinforces this truth.

The insights for living a good life arise from a reasoned, teleological reflection on our own nature and our relationships to others. This vision offers a formal framework within which to conduct our moral reasoning. Our motivation for virtue is a matter of our own integrity, following the logic of our very being.

Human moral understanding has evolved throughout our history. Ethical convictions concerning slavery, patriarchy, marriage, warfare, and many other subjects have changed. Certainly, contemporary Jews do not hold the same moral opinions as did our ancient ancestors – and that’s often a good thing.

To note the evolving nature of human moral understanding is not to assert subjectivism or relativism. Our understanding of moral truth changes, not necessarily the truth itself. Most accept an ethical understanding that slavery was always morally wrong – we humans merely came to see that truth over time.

Jewish ethics has always stressed the social dimensions of morality. We are only as well off as the least of our brothers and sisters. The essential human challenge is to affirm our dignity and interconnectedness with others and nature and overcome the isolating, selfish “egocentric” tendencies. The path of life is this – we can tame our ego and find our right place in the world by living lives of kenotic love, caring for each other and the ecosystem and attuning to the cycles, patterns, and rhythms of nature.

Salvation

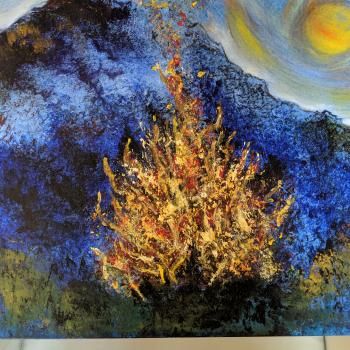

Tying the above themes together, we come to understand that the central Jewish metaphor for the human challenge is the the Exodus event – which is symbolic of each person’s liberation from the narrowness of egoism, set free to live a life of goodness in harmony with others in the wilderness.

Salvation is the totality of individual and collective actualization and fulfillment – the alignment with Power of Salvation – it is an ongoing process of love.

The majority Jewish interpretation of Genesis does not lead to conclusions of original sin. There is no “Fall” in Jewish theology that must be overcome or reversed. Humans, created in the divine image, are not separated from the divine – there is no chasm between God and humankind, no rift, no cosmic debt – no eternal gap. (The Genesis accounts are about many things – human maturation, moral awareness, even the change from hunter gather social structures to agricultural forms – but a divine curse or some form of eternal separation are not Jewish interpretations.) Human nature is certainly imperfect and limited. Sin is a reality. But the capacity for goodness and evil is inherent in human nature.

Much of Torah is about sacrificial love. Kenotic love is vital to our wholeness. When we give ourselves to realities that deserve us – we are returned to ourselves healed, whole, and transformed through divine energy – reconnected to nature and others. Flowing from the insight of empathetic reciprocity we further grasp other foundational moral imperatives – care for the needy and lowly, seeking a just society, welcoming the stranger, and drawing in the unjustly marginalized.

Kenotic love opens us toward wholeness now – we need not wait for some sense of cosmic wholeness or salvation that occurs at our death. Love provides meaning to our lives – nihilism is simply not a realistic option; to choose such a path is absurd. We cannot live with integrity as a nihilist; for every action we take implies that we find our life imbued with meaning.

Meaning is found on the journey – the meaning of life is not some grand mystery revealed on our deathbed with cloudbursts and trumpets – it’s found now – in the present moment – to live for the past or future is to live in futility. We can only live in the present moment – it is all we have – the past is gone and the future does not yet exist.

Our journey will seemingly end – no one knows what happens when we die. Judaism doesn’t engage in much speculation, either. Yet we do know that wisdom lies in embracing the core spiritual truth of our interconnectedness with others and with nature, and therefore our need for kenotic love, and our need to live according to the cycles of nature.

Jewish hope is rooted in this – love endures beyond death – how we live our lives now matters – both in the present moment and in the world to come. Something of us transcends death – may that something be a blessing toward a better world.