In his book Miracles, C.S. Lewis dwells for a peculiarly long time on the Ascension of Christ. Namely, he muses on the how onlookers perceived and today’s Christians imagine the event.

Why the sustained attention to this aspect of this moment? For one, Lewis is bound to the Neo-Platonic Christian theology that divorces the spiritual from the material, and sets the former above the latter on the scale of truth and value; however, he faces an account wherein Christ’s Ascension is not a strictly ethereal matter, but a human body lifting from the rocky ground and floating up into the sky.

However, Lewis argues that though the image of Christ’s body levitating might prove a stumblingblock to some today, it gave rise to no theological confusion in its time. We moderns, he postulates, demand explicit philosophical consistency that the ancients perceived implicitly. Christ’s disciples, by contrast, might have understood a physical ascent to be, concurrently, a spiritual one. Indeed, those who would demand theological accuracy for its own sake in images of Christ’s Ascension deserve criticism: “Purity from such [theologically inaccurate] images … will do no good if they have been banished only by logical criticism.” It is better to have some “impurity” than to enforce “purity” for logic’s sake.

When I read this, my mind immediately turned to a very popular Mormon

When I read this, my mind immediately turned to a very popular Mormon

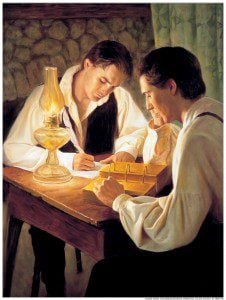

illustration [1] of Joseph Smith translating the Book of Mormon. In the image, Joseph Smith sits at a table, the Golden Plates gleaming before him, his finger tracing a line of script right-to-left across the metal leaf; Oliver Cowdery sits across from him, taking dictation. [2] At a glance, this illustration tells a readily comprehensible story.

The problem with this scene is that it never actually occurred. Joseph almost never had the plates before him as he translated. When they were by him, they were covered with a cloth. There was no line-by-line reading aloud, voice following finger, of the translated text. Sometimes there was even a curtain between Joseph and Oliver–and others, including Joseph’s wife Emma, acted as amanuensis. Indeed, Joseph carried out much of the Book of Mormon translation process–in an image infelicitously popularized by South Park–with his face buried in a hat containing a solid, brown-and-cream marbled seer stone he had found in a well.

Some, having grown up with the first illustration, are appalled to find that the latter is more historically accurate. To them, this discrepancy reeks of deception: the truth of the Book of Mormon translation process was hidden from them. Images of Joseph Smith should have shown the seer stone, the hat, the curtains, and all the other translation paraphernalia that traditional modes of interpretation have elided.

I will grant such critics this: occluding or discounting the past due to shame is unhelpful. [3] But I want to defend the first image for the same reason that C.S. Lewis defends potentially theologically misleading images of the Ascension: it is a more legible shorthand for the event. It requires some explanation—the Golden Plates are an ancient record that Joseph is translating by the gift and power of God—but it skirts the much more anthropological explanation of the traditions of folk magic in antebellum New York, of the relationship between said magic and its contemporary Christianity, of Joseph’s discovery of the seerstone, and so forth. Certainly, the LDS Church should likely produce images that are more historically accurate, but we should not altogether discard the ones that might be more succinct storytellers.

After all, religion is more than history. Kathleen Flake, chair of Mormon studies at the University of Virginia, says that reduction of faith to history is harmful to the former: “No religion I know of would want to turn its founding stories into history, at least as history is understood today in a scientific sense. Faith is not about fact; nor about fiction, for that matter. It’s certainly not a question of sophistication, at all, but of religious sense.”

In agreement with Flake, I believe that an obsession with historical verisimilitude [5] has often hobbled Mormon illustration and, in consequence, contracted the Mormon imagination. I would even argue that the obsession with historical literality, ostensibly dispensing with all unhelpful (conscious) interpretive lenses, has contributed significantly to some of today’s faith crises. Had Mormon art not been billed as communicating visions of past as it really was, fewer people would have been disappointed when they discovered that their mental movies were somewhat off.

What I would prefer would be a superfluity of modes of representation of events important to the faithful. As Samuel Brown points out, “An 8-year-old doesn’t need the same story that an adult convert in Congo needs, who doesn’t need the same story that a recovering addict needs, who doesn’t need the same story that a middle-aged professor needs.” Cultivating some plots of land for vegetable gardens makes available broader nutritional offerings than would endless but efficient fields of soy.

The Church has been improving in this respect. For example, with the release of three new endowment videos, saints are given five separate visions of Adam, Eve, Lucifer, and the Garden. [6] The International Art Competition, the winners of which are published annually in the Ensign, attracts a wide variety of expressions of faith, and the exhibits at the Museum of Church History and Art likewise model diversity.

Tomorrow I’ll talk about a specific example of innovative Mormon illustration I find intriguing.

[1] According to Wikipedia’s pithy definition, the “aim of an illustration is to elucidate or decorate a story, poem or piece of textual information by providing a visual representation of something described in the text.”

[2] Though rarer, some variants of this image show Joseph wearing the spectacle-like Urim and Thummim.

[3] Our tradition, like all traditions, arose in a particular culture of a particular time and place that will, in all likelihood, seem absurd to those from other cultural contexts. Better it is to accept our human weirdness openly. As Terryl Givens points out, if you tell a fifty-year-old about seer stones, they’re acculturated enough to a seerstone-less culture that they might be aghast at the magic of it; if you do the same to a seven-year-old, they’ll likely find it fascinating. Further, such information can productively counteract today’s hegemonic, unexamined standards of respectable behaviors and epistemologies.

[4] Note that even though the common translation story involves the Urim and Thummim, only very rarely does that artifact appear in illustrations! The Doctrine and Covenants Reader I had as a child is the only example I can think of offhand.

[5] Yet “historical verisimilitude,” I believe, describes much of Mormon art: rooted in representation that form the closest approximations we can manage of ancient Judea, old Mesoamerica, or 1820s New York. Of course, I except the bits of history that can prove troublesome–seerstones and marital quarrels over polygamy, for instance–but the mode is still that of period dress and “authentic”-looking sets. Of course, some of this obsessiveness is born of apologetics: our detractors, seeing Mormonism as a historical artifact, deploy the tools of history to “disprove” it. We return the favor. This, mixed with our theological imperative to family history, leads to the unquestioned dominance of Mormon history among homegrown Mormon academic disciplines.

[6] Notably, however, all the videos place them in a real-world paradise and then in a wilderness; one friend of mine has told me he’d love to see an endowment film in which, upon exiting the Garden, Adam is shown returning home to an urban apartment to find Lucifer enticing him in a television ad.