This morning, a deranged attacker opened fire in a Connecticut school, killing tens of children and adults. Little else is known right now about this particular shooting, although it’s another episode of a drama Americans know well. The Aurora shooting happened just this year, along with three other shootings in schools. VA Tech suffered a major shooting in 2007. Looming large in the nation’s consciousness, too, is always Columbine.

The Columbine massacre defined evangelical culture at the turn of the millennium. I remember being told to be grateful that I was homeschooled so that I wasn’t part of violence-saturated demon-worshiping high school culture. The evangelical Christian media went mad over Rachel Scott, the girl who allegedly answered with a definitive “yes” when the killers asked her if she believed in God. We were told that the two boys who attacked the school had descended into a Satanic fury, listening to Marilyn Manson, reveling in violent video games and deliberately targeting Christians out of hatred for the Truth. To make things more complicated, the identity of the Columbine martyr was just as often cited as Cassie Bernall. The Rachel Scott/Cassie Bernall story was false, but the myth is immortalized in books like Rachel’s Tears, She Said Yes, and a whole host of Christian songs. These two are the best known:

Michael W. Smith: This is Your Time

FlyLeaf: Cassie

I listened to the Smith song, although “Cassie” was have been the kind of song my church believed inspired acts of violence (demons travel in rock beats) so I didn’t learn of its existence until later.

Today’s shooting has lit up social media with incensed remarks about gun control (one way or another). But the conversation my church had about Columbine wasn’t about gun control. It was about facing martyrdom. It was about the question Michael W. Smith asks in his song: Would you deny Christ or stand by him with a gun pointed at your face? The action that evangelicalism demanded of us was only partly to address the roots of violence (Rachel’s Challenge, commendably, targets bullying in schools). Mostly, evangelical pastors and media creators urged us to examine ourselves yet again to judge the strength of our commitment. If we could not make ourselves utterly sure that we would answer the way Rachel Scott and Cassie Bernall reputedly did, we were definitely going to be Left Behind.

Pontius Pilate, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, gladiators, tigers and handguns were all necessary actors in the kind of drama evangelicalism created around Columbine. The kind of Christianity we believed in was cyclical, an endless repetition of the Crucifixion, starting with the martyrs and ending with us. We might have said we wanted to make a more peaceful world, but we didn’t believe it was possible. We certainly believed that it was out of the hands of the government; the only way to know peace was to know the Prince of Peace, we said. Missions were the solution; revivals were the enforcement. Our pastors told us that Columbine was just the beginning; 9/11 was just the beginning; this morning is probably also “just the beginning” of the Tribulation that will test every Christian to see who’s really faithful. Violence was the state of the fallen world, not a problem that policy, poverty, or culture could touch.

I learned to shoot when I was the same age as the kids at that Newtown, CT school. I was raised on NRA propaganda that my church reinforced: the government was coming to persecute us, and the saved would have to fight for the Truth if they didn’t make the Rapture. We had guns all over the house: a Kentucky rifle on the wall, Colt black powder pistols (including my own small version), a newer automatic that my father owned. Several knives, ranging in size from the length of a toothpick to one that could murder a moose. When I was 9, I could empty a round on my blackpowder pistol within 2 inches (but, since I was 9, I don’t remember how far away I was from the target). Ironically, my father didn’t hunt. He had tried once and gone soft over a wounded rabbit. But he stockpiled guns as a collector – and he joked about defending us against the liberal government. He wasn’t joking when he talked about shooting burglars.

Trouble was, I wasn’t nearly as afraid of random strangers as I was of the gun’s owner. My father had enough pent-up rage to pedal a rocket to the moon. On the nights when he screamed at my mother, my eyes wandered to the gun cabinet. I listened for the click that told me to run for the police. Fourteen years later, after college, I caught myself listening for the same sound after a long night of screaming, and that’s when I had the sense and the means to leave.

My father owned guns legally. He had not been diagnosed with any mental illness, but then again, he never went to the doctor unless he was on death’s door; let alone a psychologist. And yet, the simple possession of guns gave him superhuman power in our home. Every time I stood up to him, I imagined him shooting me. I destroyed letters and journals that contained any negativity towards him, because I imagined him shooting me. I was plagued by nightmares about getting chased and gunned down by my own father until I was 25. But years of terror don’t count as evidence for anything, right? After all, he hasn’t killed anybody yet. After all, I’m not dead. Who would have told you all that if I were? More likely it would have been an “unimaginable tragedy” that nobody could have possibly predicted.

Our insistence on being surprised by gun violence, on acting like each mass murderer invented his crime out of thin air, cripples our ability to ask the harder questions about who wants guns, who has them, and who might really turn violent and reach for one.

The NRA’s talking points never seem to address why people want guns. My father wanted guns for pride and power. He would say it was for “self-defense.” But what he calls self-defense, I call living under threat. Because at any moment he might “defend himself” against me. He taught me that guns are no danger in the hands of people who use them responsibly – and he walked that talk by always pointing the gun at the ground while loading or cleaning it, by storing it out of sight and out of reach by pets or children. But the man who taught me those things and practiced those behaviors shouldn’t have owned a gun. Because he hit my mother. If you can’t control your fists, your tongue, or your temper, how can I trust you to control your gun?

My father’s gun ownership was informed by a belief that to be masculine and to be “American” meant being armed. That’s a cultural belief, carefully inculcated by NRA fanatics who want to sell guns and pat themselves on the back. How quick would they be to relieve him of his possessions if they knew that he terrorized his family? That his wife taught their 12 year old how to drive to get away from him in a hurry?

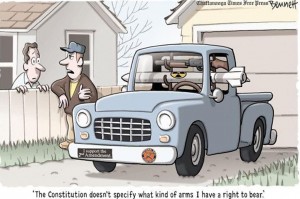

An NRA supporter on a friend’s facebook wall today argued that the deep spiritual issue affecting America is how to find and respond to people who might snap, who might go unhinged and perpetrate a mass shooting. After all, she said, criminals will always get guns if they want them badly enough. I’d rather bring up another spiritual issue:

What unfulfilled spiritual need makes a person want a gun? How can spirituality unmake the desire for dominance, the paranoia that sees enemies everywhere and defense as priority? Why do Christians trust their God so little that they stockpile instruments of killing?

Besides, if the government really does come to raid your churches and steal your freedoms, do you really think your automatic pistol is going to stop them? If criminals can “always” get guns, then so can your Christian militia. Your bigger problem is your own ideology: the more “independent” you are, the worse you are at following the orders of your ragtag revolutionary militia. Organization and strategy win wars, not isolated fanatics with closets full of beans and handguns. Prayer would be more effective (and far less likely to endanger your own children).

I’m a Unitarian Universalist now. I don’t believe in hand-wringing about the inevitability of crime. Murder can be prevented. Rape can be prevented. Mass shootings can be prevented. But it starts with giving a damn about the kind of culture you create and what your society excuses. And yes, some of the questions you have to ask sound a lot like “socialism,” because they involve admitting you are a social creature who lives in a society and whether you like it or not, you’re shaping it with your own ideas. Some of the questions you have to ask involve how to get mental health care to those who need it, how to regulate access to the most dangerous commodities, and how to pay attention to warning signs before they turn into “unimaginable” and “unforeseen” tragedies like today’s.