One of the things I am constantly thinking over, during the summer when I actually have time to think, is the tension between openness and control that constantly tugs at my course planning.

Do I make policies, procedures, assignments, and evaluations with an eye toward those students who will make the most of their opportunities to learn? Or do I focus on requirements and regulations–curtailing cheaters, prodding the lazy, forcing the unwilling, and nagging the distracted?

This is not a dilemma that exists only for educators. Most organizations and businesses, especially those that operate beyond the local level, must operate with the assumption that people will screw up. They must account for laziness, incompetence, apathy, mischievousness, greed, and criminality.

I’m always pulled toward more open pedagogies: elective assignments, “flipped” classrooms, optional readings, self-directed learning. But whenever I think of how to implement them, I imagine how the screw-ups will screw it up.

So my syllabus gets longer every year, mostly to cover negative situations that happened in previous years. Someone does something stupid (sometimes, I’m the someone), and I write a new paragraph of warning, a new policy, a re-clarified policy, another half-sentence description, an explanatory chart.

Similarly, businesses and organizations that begin their operations with openness and generosity often find themselves having to write restrictive or preventative policies, after an experience of malicious advantage-taking, vandalism, or theft.

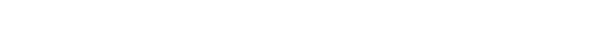

So, after Google allowed crowd-sourced edits to its mapping website, they quickly discovered that someone had taken advantage of their openness by dropping a pin with a racist vulgarity at the White House’s coordinates. (This is why we can’t have nice things.)

Wikipedia has made several changes to its editorial structures, sometimes to account for its exploding popularity, but sometimes in response to malicious, self-serving, and profiteering actions.

Online enterprises aren’t the only ones troubled by the phenomenon: many of my fellow faculty members have had the experience of leaving free books out for students to take, only to discover that a single student takes all the books and sells them on Amazon Marketplace.

Similarly, a Goodwill store near where I used to live discontinued a discount that no doubt helped many people, after a few were using it to make money. They used to have Wedding Dress Wednesdays, where donated wedding dresses were on deep discount (most were under $10). They discovered that a few local homemakers were buying the most promising dresses, cleaning and mending them, and selling them for a substantial profit on eBay and Craigslist.

The Goodwill case was especially interesting. Personally, I appreciated the industry and enterprise of the homemakers, but I also understood why the store managers were distressed. The women were buying dresses for $5 that someone else might honestly need, and need at exactly $5; they were also sourcing their materials through donations that were not intended to subsidize their business. On the other hand, the women believed they were taking dresses that could not be used as is and making them beautiful (or at least usable).

When the discount was suspended, though, I think everyone lost. Now, instead of picked-over wedding dresses at $5, there are no wedding dresses at $5. Perhaps an honest conversation with the budding businesswomen might have resulted in a happy compromise–all wedding dresses going unsold for three months could have been sold to them at the discounted price?

In any case, it’s not that the more restrictive policies are wrong, but they do tend to have the effect of emphasizing and even advertising the pettiest aspects of humanity.

I hate writing the academic integrity paragraph on my syllabus. I have to name all the ways a student can cheat, because someone has done it in the past, and I have to make sure that whoever does it in the future can legitimately be held responsible for his misdeeds.

I’ve done my best to rewrite it to emphasize what ought to be done, rather than what ought not to be done, but I can’t do away with the finger-wagging part entirely.

And that seems a shame.

On the other hand, pretending that there is no such thing as the human tendency to sin and selfishness is no less a shame.