We live in a time in which most of us are so savvy that we’re in danger of being cynical; so wise to the way the world “actually” works and exploring the hidden side of everything that we are apt to do nothing.

Foreign aid? Creates dependency, is imperialism disguised as benevolence, more harm than good.

Altruism? Just another way of asserting one’s superiority, ensuring the survival of one’s seed; an ego stroke.

“Gift” catalogs where little kids can “buy goats” for families in need? Consumerism disguised as charity.

And so on.

Food drives are no exception. Several years ago Slate.com ran a characteristically cantankerous article on “why food drives are a terrible idea” because food banks “need your money, not your random old food.”

Well, that’s true. Food banks purchase goods in bulk, so the $2 you spend on a can of minestrone at the grocery store could probably buy three or four cans of the very same thing if you just donate the money directly to a local or regional food bank.

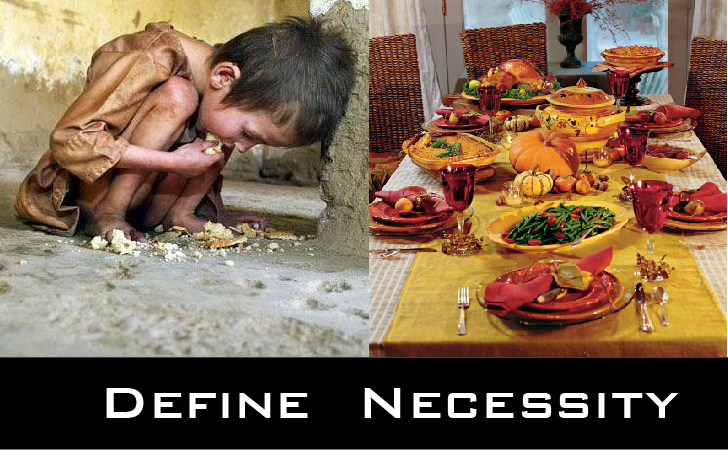

And yet I think there is something in the small, symbolic act of actually putting your hands on food, feeling its weight and shape, and offering it as a gift to some unseen person, who will, no doubt, receive it with gratitude, humility, and possibly, sadly, a bit of shame.

vastateparksstaff

via Flickr Creative Commons.

Last week my pastor preached with a can of Progresso soup in his hands. He’d run into a new member of the church at a coffee shop, who’d eagerly pulled the can out and handed it to the Reverend, who was a bit perplexed. The man explained:

“Each time I go to the store I get all the stuff we need, and then I add a can for the food drive.”

Every time. Add a can. A visible, tangible reminder of the need of others. A can that the city-dwelling man would have to haul around on his back across blocks and on the bus and up the stairs to his apartment, down the stairs and across the blocks and on the bus to the collection point. A tiny, edible burden.

Our pastor, who had probably read the Slate article or something like it, was inclined to be dismissive, he confessed. And then he thought about it…what it meant to remember, each time you go to the grocery store; each time you eat, that there are those who do not have enough, and to set aside a little to share.

My childrens’ school held a food drive this past fall. In age-appropriate terms, the kids learned about how some children — who eat breakfast and lunch at school most days — get hungry during school breaks. The kids brought in items much like the ones they eat for lunch and snack, and sorted and packed them into friendly bundles, perhaps (I’m not sure) with drawings decorating the bags — each with an entree, some fruit, a side or two, and a drink.

I like this. It is tangible. It is incarnational. Is it efficient? Does it solve every problem? Maybe not. But I am enough of a cranky optimist and a reluctant Romantic to think that there is that of love shared in the hauling of the cans; in the assembling of the breakfasts and lunches to be eaten in the dark, cold days of winter when kids who get free meals at school go hungry at home.

It is easier than ever to throw our money at social problems. I can donate to a cause by adding a dollar or two to my grocery bill or by texting a certain code to a certain number. I can use PayPal. These are clean, easy, efficient, and possibly effective…though they run the risk of being thoughtless.

I am all for putting resources where they can do the most good. But I am still cheered by the sight of food collected, sorted, and packed with love to be shared and received with gratitude.

At the end of my book on food, I quote N.T. Wright:

Don’t despise the small but significant symbolic act. We live still in this modernist dream which says, “Unless you can chance the whole thing, it’s not even worth trying.” That’s not what Jesus did. Jesus did small but significant symbolic acts, each one of which was freighted with kingdom meaning. God probably doesn’t want you to reorganize [everything] overnight. Learn to be symbol-makers and storytellers for the kingdom. Learn to model genuine humanness in your worship and your stewardship and your relationships — the Church’s task, vis-a-vis the world, is to model true humanness as a sign, as an invitation.”