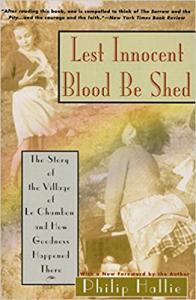

Philip Hallie’s marvelous book Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed tells the true story of Le Chambon, a French town where Pastor André Trocmé’s church, under the Nazi occupation, provided Jews with food, shelter, protection, and means of escape. Despite the disapproval of many, Trocmé and his church persevered in doing what they believed was right. As a result, “Le Chambon became the safest place for Jews in Europe.” [1] Over a period of about four years, the church rescued nearly twenty-five hundred Jews.

Philip Hallie’s marvelous book Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed tells the true story of Le Chambon, a French town where Pastor André Trocmé’s church, under the Nazi occupation, provided Jews with food, shelter, protection, and means of escape. Despite the disapproval of many, Trocmé and his church persevered in doing what they believed was right. As a result, “Le Chambon became the safest place for Jews in Europe.” [1] Over a period of about four years, the church rescued nearly twenty-five hundred Jews.

The Holocaust’s cruelty obsessed Hallie. He said he’d become “bitterly angry” and “over the years [of studying the Holocaust] I had dug myself into Hell.” Hallie speaks of a life-changing day when he discovered the stories of Christians in Le Chambon rescuing Jews, at peril of their own imprisonment and death. As he read, it surprised him to break into tears in what he called “an expression of moral praise.” Hallie later described the love of the church at Le Chambon:

It was this strenuous, this extraordinary obligation that… Trocmé expressed to the people in the big gray church. The love they preached was not simply adoration; nor was it simply a love of moral purity, of keeping one’s hands clean of evil. It was not a love of private ecstasy or a private retreat from evil. It was an active, dangerous love that brought help to those who needed it most. [2]

The day Hallie read of those flawed but loving Christians, he caught a view of God in the goodness they had done. He went home and spent a busy evening with family, then found himself in bed, weeping again over what happened in Le Chambon. Hallie wrote,

When I lay on my back in bed with my eyes closed, I saw more clearly than ever the images that had made me weep. I saw the two clumsy khaki-colored buses of the Vichy French police pull into the village square. I saw the police captain facing the pastor of the village and warning him that if he did not give up the names of the Jews they had been sheltering in the village, he and his fellow pastor, as well as the families who had been caring for the Jews, would be arrested. I saw the pastor refuse to give up these people who had been strangers in his village, even at the risk of his own destruction.

Then I saw the only Jew the police could find, sitting in an otherwise empty bus. I saw a thirteen-year-old boy, the son of the pastor, pass a piece of his precious chocolate through the window to the prisoner, while twenty gendarmes who were guarding the lone prisoner watched. And then I saw the villagers passing their little gifts through the window until there were gifts all around him—most of them food in those hungry days during the German occupation of France.

Lying there in bed, I began to weep again. I thought, Why run away from what is excellent simply because it goes through you like a spear? Lying there, I knew… a certain region of my mind contained an awareness of men and women in bloody white coats [committing unspeakable atrocities to] six- or seven- or eight-year-old Jewish children…. All of this I knew. But why not know joy?… Why must life be for me that vision of… children [hideously brutalized]? Something had happened, had happened for years in that mountain village. Why should I be afraid of it?

To the dismay of my wife, I left the bed unable to say a word, dressed, crossed the dark campus on a starless night, and read again those few pages on the village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. And to my surprise, again the spear, again the tears, again the frantic, painful pleasure that spills into the mind when a deep, deep need is being satisfied, or when a deep wound is starting to heal. [3]

Philosophy professor Eleonore Stump tells of coming to know Jesus through studying the problem of evil and suffering. Reflecting on her own experience (and Hallie’s), Stump writes,

So, in an odd sort of way, the mirror of evil can also lead us to God. A loathing focus on the evils of our world and ourselves prepares us to be the more startled by the taste of true goodness when we find it and the more determined to follow that taste until we see where it leads. And where it leads is to the truest goodness…to the sort of goodness of which the Chambonnais’s goodness is only a tepid aftertaste. The mirror of evil becomes translucent, and we can see through it to the goodness of God…. So you can come to Christ contemplating evil in a world of goodness, or contemplating goodness in a world of evil. [4]

One mother—her three children saved by the people of Le Chambon—said, “The Holocaust was storm, lightning, thunder, wind, rain, yes. And Le Chambon was the rainbow.” [5]

The history of the human race cannot be reduced to the Holocaust. There was and is considerable goodness in the world outside the Holocaust. Yet even inside it, in places like Le Chambon, a costly and beautiful goodness lives.

Excerpted from If God Is Good: Faith in the Midst of Suffering and Evil.

Read more about Le Chambon from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

[1] Philip Paul Hallie, Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed (New York: HarperCollins, 1994), 4.

[2] Hallie, Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed, 129.

[3] Hallie, Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed, 110–11.

[4] Eleonore Stump, “The Mirror of Evil,” in God and the Philosophers, ed. Thomas V. Morris (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 235

[5] Os Guinness, Unspeakable (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 2005), 227.