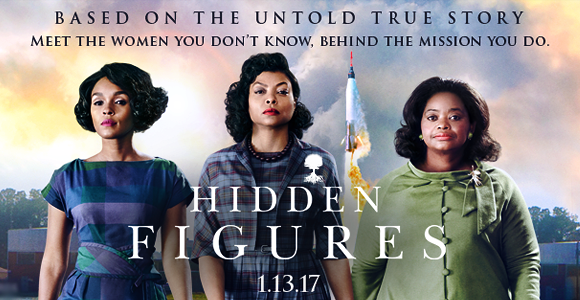

I was delighted to attend an advance screening tonight of the movie Hidden Figures, and I am enthusiastically recommending it. It combines so much into one movie: it is based on real historical events; it has romance; it is a feel-good, family-friendly movie with a powerful positive message and excellent role models; it addresses issues of racism, sexism, and social change; and it revolves around (or orbits, if you prefer) a key moment in the history of NASA and America’s effort to put astronauts in space. I won’t worry about spoilers, since it is based on historical events – although neglected ones, as the movie’s title (which is the same as the bestselling book the movie is based on) highlights. This is a story that deserves to be told (and one part of which, interestingly enough, just recently got attention on the time travel TV show Timeless, which I’ve been watching).

The story is set in a time when “computers” were people – before machines were used to carry out calculations, people did them, and their job bore the title “computers.”

And it is set in an era when at a place like NASA, there were separate rooms for “Colored Computers” and those who were white.

Into that context, the movie begins with the story of Katharine Johnson as a child prodigy, who receives a scholarship to “the best school for negroes” in her home state of West Virginia. It soon skips ahead to her adult life, working for NASA, and while the story remains focused on her, it also pans out to include two of her friends whose achievements were equally noteworthy: Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson. We first encounter them at the side of the road on their way to work, where their car has broken down. A police officer pulls up, and expresses surprise that NASA hires people of color. In the end, he gives them an escort, and Mary describes the situation – three black women chasing a police car on the highway – as a “God-ordained miracle.”

At NASA, the fact that the Russians are outpacing them is a cause for more than mere concern – there is fear of the potential for the same rockets that carry cosmonauts into space to rain thermonuclear bombs on America. Everyone is working hard on the problem, and NASA has also ordered its first IBM 7090 DPS. (We later learn that they had not made sure that the doors to the room set aside for it were large enough for it to fit through).

Throughout the movie, we see the discrimination that existed not only against African Americans, but against women (as the character Vivian Mitchell puts it, NASA is “fast with rocket ships, slow with advancement.”) Watching from today’s perspective, one cannot help but cringe when we see a stellar mathematician handed a trash can because she is assumed to be the janitor, and to be angry that she had to run to another building to use the nearest bathroom for colored women. But we cheer when those who currently have roles of authority do the right thing, such as when Al Harrison, a fictionalized manager at NASA, takes a sledgehammer to the sign delineating the bathroom as for colored women, and takes other steps, such as recognizing that from a purely practical perspective, if Katherine Johnson attended meetings for which there was no precedent for any woman to attend, never mind an African-American woman, the chances for their space program to succeed would be so much greater. And we are impressed when individuals like John Glenn simply treat the “colored computers” like anyone else, going over to greet them when he first arrives at Langley, and simply asking for the smart girl to check the numbers when there is some uncertainty about the calculations right before his big Mercury launch.

The threat of machine computers to jobs was felt immediately, and Dorothy Vaughan took the lead by learning Fortran so that she and her team could have a place in the new environment the IBM would create. One powerful moment is when she and her children are expelled from their public library because she was in the main section, because the colored section didn’t have what she needed. As they ride in the back of the bus on the way home, we learn that she took the book she needed before being expelled, and she justified it by saying that she pays the taxes for the library just like everyone else. Later in the movie, she gets the IBM computer working.

The threat of machine computers to jobs was felt immediately, and Dorothy Vaughan took the lead by learning Fortran so that she and her team could have a place in the new environment the IBM would create. One powerful moment is when she and her children are expelled from their public library because she was in the main section, because the colored section didn’t have what she needed. As they ride in the back of the bus on the way home, we learn that she took the book she needed before being expelled, and she justified it by saying that she pays the taxes for the library just like everyone else. Later in the movie, she gets the IBM computer working.

By the end of the film, we learn that Mary Jackson did indeed become the first female African-American engineer, and Dorothy Vaughan became the first African-American supervisor at NASA. Jackson, in seeking to achieve her dream, goes to court in an attempt to be allowed to take classes at the only school where she can, which does not enroll black students. She emphasizes to the judge the importance of firsts, having done her research about the judge’s own pioneering achievements in relation to his family. And then she asks him which of the court cases that day are going to be remembered a century later – and also emphasizes the opportunity for this to be remembered as a first of more than one kind for their state. It is one of the most poignant and powerful moments in the movie, because it shows how determination and courage coupled with research and well-planned speech can bring about significant change.

For those interested in the kinds of subjects that I am, we see two things that are significant over the course of the film. As far as the relationship of religion and science is concerned, there is no antagonism. When John Glenn’s capsule in orbit might have a problem with its heat shield, people pray – but no one thinks that means that the calculations become any less important or necessary. And we also see the impact of Martin Luther King Jr., and the minister in the congregation that these three NASA employees attend, in encouraging still further social change, while also giving thanks to God for developments such as the very fact that they have the jobs that they do. The challenge for religion is often how to foster both thanksgiving for what we have but also determined effort to make things better still. It is the same challenge that society as a whole faces, and it is not always easy to do both, but when it happens, the impact can be amazing. And so it is a good movie for church groups to go to see – whether the conversations that occur as a result are more “how can we continue to make a difference in our time?” or “how could white Christians have not been advocating for equality and working to end segregation? And in what ways are we doing the same thing in relation to problems in the present day?”

I should add that I took my wife and son with me to see the movie, and they loved it as well. It really is a great film for anyone who has any interest in history, biography, and/or social issues and the part that individuals with courage play in bringing about not merely changes in laws and rules but in hearts and minds. I very highly recommend it.