“Sin Boldly: Christian Ethics for a Broken World”

Roger E. Olson, Foy Valentine Professor of Christian Theology and Ethics, George W. Truett Theological Seminary, Baylor University

The Maston Lecture, November 6, 2013, George W. Truett Theological Seminary

Few movies have affected me as strongly as the 2011 film “Machine Gun Preacher” starring Gerard Butler as Sam Childers, drug addict turned Christian missionary who takes up an AK-47 for Jesus in the Sudan. Based on Childers’s true life story, the movie raises gut-wrenching questions about Christian ethics and especially whether use of deadly force is ever justified for the Christian. As those who have seen the movie know, Childers joined a mission trip to the Sudan and there encountered children being slaughtered and forced to kill others by the so-called Lord’s Resistance Army. Faced with the opportunity to resist this horror with deadly force, he reluctantly accepted it and became the Lord’s Resistance Army’s worst nightmare. Because of his violent resistance to LRA numerous children’s lives were saved and many more were rescued from child soldierhood.

The movie raises the question—Put in Sam Childers’s place, what would I do? But, of course, that’s unlikely. So it raises another, more realistic question—What should I, as a Christian theologian and ethicist, tell others about Christian use of force in a world of monsters whose victims include small children?

It’s easy to come away from watching that movie or reading about the abolitionist John Brown or Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s involvement in the plot to kill Hitler and say “Oh, yes, well, put in those positions I would probably do the same.” It’s harder to give ethical advice that justifies Christian use of force—even in defense of starving children or against military dictatorships that “disappear” thousands of dissidents such as was the case in Argentina and Chile in the 1980s.

To be sure “Sin boldly” is an unusual theme for a talk about Christian ethics in a seminary chapel. And yet, as I will argue, it’s worth thinking and talking about in such a broken world as ours. Contrary to certain modern and contemporary Christian ethicists who say an absolute “no” to all Christian use of force I must reluctantly say, with Luther, “Sin boldly…and repent more boldly still.”

Yes, “Sin boldly” is Martin Luther’s best known quote—at least among university students. In a letter to his former Greek professor and right-hand man in Reformation Philip Melanchthon dated August 1, 1521, the Reformer wrote to his friend:

If you are a preacher of mercy, do not preach an imaginary but the true mercy. … Be a sinner and sin boldly, but believe and rejoice in Christ even more boldly for He is victorious over sin, death and the world. As long as we are here in this world we have to sin. This life is not a dwelling place of righteousness, but, as Peter says, “we look for a new heaven and a new earth in which righteousness dwells.” It is enough that by the riches of God’s glory we have come to know the Lamb that takes away the sins of the world. No sin will separate us from the Lamb…. Do you think that the purchase price that was paid for the redemption of your sins is too small? Pray boldly—you are too mighty a sinner not to!

But “sin boldly” goes against the grain of our Christian, and I might add American, perfectionism. Isn’t it always possible to do the right thing? The perfect thing? Isn’t that what Christian ethics is all about? To tell us what is the perfectly right thing to do in every foreseeable situation? Isn’t being American being perfectly right?

My thesis here today is that this perfectionism is wrong; it forgets the truth of the old maxim that “the perfect is often the enemy of the good.” On the other hand, perfection is an impossible ideal worth striving for—with God’s help. But when perfection proves impossible, as is so often the case in this broken world, God’s mercy is available. The Kingdom of God is not yet and, in the meantime, this time between the times, it is our duty as citizens of that Kingdom yet to come to approximate it in real and living ways and sometimes that means using the powerful means that we have. When we must use force, coercion, however, we must avoid baptizing it as righteous and regard it rather as a sign of our brokenness, the world’s brokenness, and the not yetness of the Kingdom.

This talk arises from my experience of teaching a course on Christian social ethics almost thirty times in this place—once each semester and occasionally twice in a semester. I have chosen for my students to read and discuss four great recent and contemporary Christian social ethicists—Walter Rauschenbusch, Reinhold Niebuhr, Gustavo Gutierrez and John Howard Yoder. Reading Yoder led me to a study of Stanley Hauerwas whose Christian ethic is strongly informed by the Mennonite thinker. So here I will combine Yoder and Hauerwas, overlooking their differences, and refer to their Christian perspective on social ethics as “Yoder-Hauerwas” or, simply, “Christian perfectionism.”

Every semester as I read these great Christian thinkers with my students I experience cognitive dissonance. As I read Rauschenbusch, whichever of his books I’ve chosen that semester, I find myself agreeing with him almost completely. But when I read Niebuhr, who harshly disagreed with Rauschenbusch about fundamental issues, I find myself vigorously agreeing with him, too! Then, when I read Gutierrez, even in those areas where he disagrees with Rauschenbusch and Niebuhr I succumb to near total agreement with him! Finally, like so many who read Yoder and Hauerwas, I find myself agreeing with them—even where they diverge radically from Rauschenbusch, Niebuhr and Gutierrez! Either this is a sign of mental weakness or I am simply observing that each has a partial grasp on truth, such that what nineteenth century theologian Horace Bushnell called “Christian comprehensiveness” lies somewhere behind and within all of them. Of course, I prefer to think the latter is the case.

One thing I have observed as a historical theologian is how often theologians, and I’m sure practitioners of other disciplines, make a great name for themselves by seeming to disagree strenuously with someone else who has a great name when, in fact, there’s truth in both perspectives and they in fact need each other for balance and comprehensiveness. A famous example of this from the last century was the debate between Karl Barth and his fellow Swiss “dialectical theologian” Emil Brunner over “natural theology.” It reminds one of the old beer commercial where two barroom friends debate about whether their favorite brew “tastes good” or is “less filling.”

For all their differences, I believe, Rauschenbusch, Niebuhr, Gutierrez, and Yoder-Hauerwas need each other; all have something good and right and true to contribute to a contemporary Christian social ethic and each corrects potential errors in the others.

One talk is too brief to cover all the subjects these Christian ethicists deal with, so here I am going to focus on the one relevant to the case study I began with—the Machine Gun Preacher. Is Christian involvement in social unrest, social struggle, the often messy, rough and tumble of politics, even violence ever ethically justifiable? Should Christians engage in attempts to bring about justice in this broken world, even if that requires participating in its brokenness? Or ought Christians to sit on the sidelines of social conflict and beam messages of love into the fray hoping God will use them to bring about some modicum of peace and justice?

Is this a relevant question today? Well, anyone who is familiar with the popularity of Hauerwas’s ethic of “the Christian colony” within the world knows it’s a relevant question. Many Christian people, especially young people, are attracted to Hauerwas’s approach which even Hauerwas admits is largely inspired by the earlier ethical writings of Yoder. Christian pacifism and perfectionism are extremely popular today, especially among reflective young Christians who care deeply about issues of violence, poverty, war, empire and the threat of Constantinian theocracy. So, yes, this is an extremely relevant issue for every concerned Christian to consider.

Before diving into it, however, I think it’s best to reveal my own approach to Christian ethics in general and social ethics in particular. Ethics, including Christian ethics, is no exact science; there are many perspectives on it—including differing definitions of what ethics is. I suspect the popular, what I call “folk,” approach to ethics, especially among conservative Christians, is learning and following rules. Adults especially like this approach when dealing with young people always on the verge of rebellion. “Follow the rules!” we like to say. Most of us know, however, that rules often conflict and there are situations where no rule applies, at least not clearly or directly, and rules need grounding, justification. Why that rule and not another one?

This disillusionment with rules often causes especially young people at a certain stage of moral development to rush to embrace “situation ethics,” the idea that every situation of moral choice is unique and that rules are generally unreliable and often just wrong. Situation ethics, popularized by radical theologian Joseph Fletcher in his 1966 book by that name, says there are no absolutes except love. It attempts to leave it to individuals to apply love directly, as led by intuition, without mediating principles, to every moral dilemma “in that moment.” Of course, this approach to ethics is overly simplistic and individualized and leads into relativism. And yet, it was a natural reaction to the absolutism of some rule-based ethics, especially conservative religious ones that often ignore the exigencies of unexpected existential situations and demands for moral decision and action where the known rules would lead one to act irresponsibly. Kierkegaard’s “teleological suspension of the ethical” then lurks in every situation. Ethical anarchy results.

I believe all ethics is rooted and grounded in stories, grand narratives about reality and especially about “the good life.” Here I agree with Hauerwas who, in The Peaceable Kingdom, rightly argues that there are no neutral, value-free, not already committed ethical norms. All ethical norms are tied to narratives, stories about the meaning of life—why we are here. So let me propose this definition of ethics:

Ethics is deciding and acting in accordance with the good life, properly understood. It is developing a character, a set of virtues, consistent with the good life and making decisions to “do the right thing” based on the good life and the character, virtues, consistent with it.

So what is the Christian vision of the good life? I propose two biblical texts—one from the Hebrew Bible and one from the New Testament—that especially clearly reveal God’s idea of the good life: Isaiah 65:17-25 and Matthew 5-7. Time prevents me from reading all of that, so, relying on my hearers’ familiarity with Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, I will read only Isaiah 65:17-25:

See, I will create

new heavens and a new earth.

The former things will not be remembered,

nor will they come to mind.

18 But be glad and rejoice forever

in what I will create,

for I will create Jerusalem to be a delight

and its people a joy.

19 I will rejoice over Jerusalem

and take delight in my people;

the sound of weeping and of crying

will be heard in it no more.

20 “Never again will there be in it

an infant who lives but a few days,

or an old man who does not live out his years;

the one who dies at a hundred

will be thought a mere child;

the one who fails to reach a hundred

will be considered accursed.

21 They will build houses and dwell in them;

they will plant vineyards and eat their fruit.

22 No longer will they build houses and others live in them,

or plant and others eat.

For as the days of a tree,

so will be the days of my people;

my chosen ones will long enjoy

the work of their hands.

23 They will not labor in vain,

nor will they bear children doomed to misfortune;

for they will be a people blessed by the Lord,

they and their descendants with them.

24 Before they call I will answer;

while they are still speaking I will hear.

25 The wolf and the lamb will feed together,

and the lion will eat straw like the ox,

and dust will be the serpent’s food.

They will neither harm nor destroy

on all my holy mountain,”

says the Lord. (NIV)

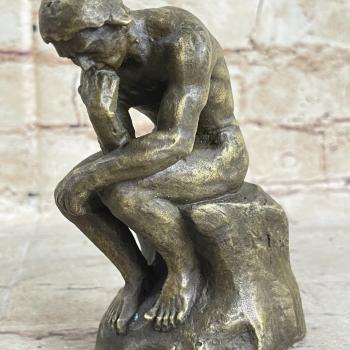

I propose that this biblical “picture” of the good life is depicted as well as can be in a picture in Edward Hicks’s 1833 painting “The Peaceable Kingdom.” The one word for it is “Shalom”—meaning well-being.

In Isaiah the focus is on peace, prosperity and long life for all. In Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount the focus is on self-sacrificing love for others, everyone looking out for others’ well-being, giving and forgiving.

This “Shalom” is the Christian vision of the good life; it is the life to come, here on earth, as N. T. Wright rightly emphasizes in his 2008 book Surprised by Hope. This is the story of the meaning of life the Bible gives us; it is our telos and God’s. Christian ethics lives from this; we seek to be persons whose character is shaped by this vision and, at our best, we try to make this world as much like that as possible. Or we should.

But the messiness of Christian social ethics, the reason for all its troubles, appears the moment we add something to Hicks’ beautiful picture—the Lord’s Resistance Army enslaving and slaughtering the children. Suddenly we are reminded that this world is not the Kingdom of God, is not a place of Shalom. Then Christian ethics becomes suddenly complicated, caught between its highest good, its vision of the good life, and what Freud called “the reality principle.” What ought Christians with power, and we all have some power, do in a world inhabited by moral monsters?

Bear with me now as I go through the basic ideas of Rauschenbusch, Niebuhr, Gutierrez and Yoder-Hauerwas. I choose these because they are representative of modern and contemporary Christian social ethics and each has a distinctive perspective on the crucial question at hand—what should Christians with power, driven by their vision of Shalom, do in a broken world such as this one?

Walter Rauschenbusch was a Baptist. That’s the first thing we need to know about him; he was one of us, he belonged to our tribe. He taught church history at the oldest Baptist seminary in North America and participated in the progressive movement that thrived in his home city of Rochester, New York a century ago. He was a leading spokesman for the Social Gospel—the Christian wing of the progressive movement that sought justice for workers, children, women, minorities and the poor. He was a friend of John D. Rockefeller, also a Baptist, but also the most notorious “robber baron” of his day. And yet Rauschenbusch wrote books harshly critical of the captains of industry and American capitalism in general. Among them were Christianity and the Social Crisis in 1907, Christianizing the Social Order in 1912, and A Theology for the Social Gospel in 1918.

For Rauschenbusch, the Kingdom of God, understood as benevolent fraternity, loving brotherhood among all people, was the heart of Jesus’s message and example. For him, a social order brought completely under the law of love as taught by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount was the concrete outworking within history of Shalom and was something Christians should strive for and expect to achieve to a very high degree. He denied perfection, but argued that it would be possible to approximate the Kingdom of God as he understood it if Christians with power would throw their moral weight and political influence behind the progressive movement and democratize every corner of society.

Rauschenbusch clearly and strongly believed in Christian involvement in reforming the social order—even to the point of taking up the reigns of power, if offered them by a free electorate. He had a clear eyed vision of the direction history, meaning the progressive evolution of the social order, should take—toward the full democratization of everything including the economy. He regarded Jesus as, among other things, a prophet of democracy, of equality, and of equal fraternity among all people. For Rauschenbusch, the good life, the life organized according to love, would be a voluntary brotherhood based on cooperation rather than competition and it would be achieved through moral persuasion and, when necessary, pressure, but not violence. According to him the fullness of the Kingdom of God, the social expression of Shalom, is “always but coming.” In other words, it is always coming insofar as we strive for it through social and political activism for reform, but we should not expect it to arrive in its perfection or completion until Jesus returns.

Rauschenbusch anticipated many objections and answered them. One that Yoder-Hauerwas followers, among others, would probably ask him is why, if Christian participation in politics using power is the right thing to do, the Christians’ mandate, it is nowhere commanded in the New Testament? Here is his response in The Social Principles of Jesus (1917):

From the beginning an emancipating force resided in Christianity which was bound to register its effects in political life. But in an age of despotism it might have to confine its political morality to the duty of patient submission, and content itself with offering little sanctuaries of freedom to the oppressed in the Christian fraternities. Today, in the age of democracy, it has become immoral to endure private ownership of government. It is no longer a sufficient righteousness to live a good life in private. Christianity needs an ethic of public life. (49)

In other words, given our changed social and political situation, in which Christians have freedom to push for reforms in government and the economy and in which Christians have social and political power, it is downright sinful to sit on the sidelines and allow evil to prevail. This is a broken world, but it can be fixed if enough Christians join the progressive movement for reform toward equality.

Hauerwas is right that Rauschenbusch’s Social Gospel was a social ethic for Christians who think they own the culture. Without doubt Rauschenbusch thought America to be a Christian country that is only halfway Christianized. He did, however, argue for Christian cooperation with non-Christians, especially Jews, who share our vision of Shalom. But he did not anticipate the cultural pluralism of contemporary America. And there was a note of triumphalism in his reforming program. Today Christians need to grapple with the reality that neither America nor any other country is Christian. The idea of a “Christian nation” is a myth; about that my friend Greg Boyd is entirely correct.

As we will see, there are other flaws in Rauschenbusch’s social ethic, ones ably pointed out, if somewhat inflated, by Niebuhr. Nevertheless, Rauschenbusch inspired Martin Luther King, Jr. and other later Christian and some non-Christian social reformers. I would go so far as to argue that the fall of Apartheid in South Africa was indirectly helped by Rauschenbusch and the Social Gospel insofar as they pioneered modern progressive Christian social and political activism.

What advice would Rauschenbusch give to the Machine Gun Preacher? Well, he did not believe in violence—even as a necessary evil. Yes, he permitted confrontation and conflict, but not physical violence. That, he believed, was contrary to the spirit of Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount. He would applaud the Preacher for daring to get involved in direct ways and for seeking to emancipate the child soldiers of the Sudan, but he would urge him to stop short of using deadly force.

But, Niebuhr might ask, how exactly do you stop the Lord’s Resistance Army without violence?

Our next Christian social ethicist is Reinhold Niebuhr, probably the most influential American theologian of the twentieth century. Niebuhr earned his stripes, so to speak, while pastoring in Detroit during times of social and economic unrest in the automobile industry. He brought union leaders to speak in his church and preached and wrote articles against Henry Ford and other industrialists for not providing, among other things workers needed, workers compensation for those injured on the assemblies lines. Eventually he taught Christian ethics at Union Theological Seminary in New York and wrote numerous books mostly about social ethics. His picture graced the cover of Time magazine’s twenty-fifth anniversary issue in 1948. Several presidents from Carter to Obama have credited Niebuhr as their “favorite” theologian or philosopher.

But, ironically, in spite of his progressive social and political ideas, Niebuhr made his name by criticizing the Social Gospel! After World War 1 and the ensuing turmoil in Europe and America, especially during the Great Depression, and with the rise of Fascism in Europe, Niebuhr became disillusioned with the Social Gospel’s optimism about the Kingdom of God and our human ability to achieve it through love, persuasion and patient pressure. He saw, for example, that no amount of moral persuasion was making a dent in the great American industrialists’ oppression of their workers. And he ridiculed the very idea that we should ask African-Americans and other oppressed minorities simply to forgive their oppressors.

In other words, Niebuhr looked at Hicks’s picture of The Peaceable Kingdom and saw an eschatological, utopian, impossible ideal. The real picture, the picture we must have of this world as it is and always will be until the end, is one of massive injustice, oppression and violence of the powerful against the powerless. The Peaceable Kingdom picture of Shalom should drive us forward, to purify all our accomplishments and achievements, but we should not think it a realistic scenario for this-worldly history. Insofar as we do, he feared, we will inevitably take some human society, ours, for example, and lay The Peaceable Kingdom picture over it and claim we have “almost arrived.”

Niebuhr was allergic to optimism. His social ethic was labeled “Christian Realism.” Some preferred to call it unchristian pessimism! But Niebuhr feared our natural, fallen human tendency to pat ourselves on the back and baptize our social programs and arrangements as “Christian” and fall into complacency. We aim for love, he said, and miss justice. That’s because justice is messy and often seems contrary to the true spirit of love which is perfect selflessness. Justice includes the self in its calculations of conflicting claims about rights. Justice recognizes the world for what it is—a battlefield in which all, both righteous and evil, are infected with egoism and have a tendency to claim too much moral rightness for themselves. In fact, according to Niebuhr, all our motives are tainted and all our causes and programs are broken and all our achievements of justice are at best partial.

Because the world is so broken, Niebuhr believed, if we Christians are to be involved and effective in bringing about even approximations of justice, partial achievements of Shalom, we must be willing to compromise with the ungodly. Of course, he didn’t mean “compromise” as in “capitulate” to sin; he meant looking around for philosophies, movements, ideas that may not be rooted in revelation or rise to biblical standards of love and join with them, use them, cooperate with them insofar as they are imperfect tools for “making the best of” this sinful, broken, fallen world. Niebuhr realized and admitted that such compromises would necessarily involve Christians in sin, but, he believed, the only alternative is withdrawal from the fight for justice and that, he believed, would be irresponsible.

For Niebuhr, in contrast to Rauschenbusch, “justice” falls far short of love. The love Jesus taught and called for is perfect selflessness, disinterested, sacrificial benevolence that gives whatever one has to the nearest needy neighbor without weighing what he deserves or she will do with it. Love simply gives. Justice, on the other hand, calculates. It weighs competing interests and needs and rights and uses reason to establish balances of power. It seeks freedom and equality for all without utopian illusions; it settles for modicums of freedom and equality and requires messy, risky, struggles for them.

According to Niebuhr, love injects mercy into justice and calls it to ever higher achievements of equality among people. But justice makes love concrete in the real, broken world where absolute love between competing powers is impossible.

Niebuhr’s was a social ethic for people with a tragic sense of history, for those who feel compelled to become involved in the rough and tumble world of politics and social unrest toward justice, for those who are willing to risk disobedience to perfection for the sake of establishing a more just and equitable world.

Let’s look at Martin Luther King’s civil rights movement during the 1960s and see in it elements of both Rauschenbusch and Niebuhr. King frequently talked about the goal of the movement as “brotherhood” and a “commonwealth of equals,” even as “the beloved community.” That’s Rauschenbusch language. And he eschewed violence as a means of achieving justice for the oppressed; he urged use of loving persuasion toward enemies and oppressors. On the other hand, he engaged in organized struggles, confrontations and conflict and risked violence as a consequence of his non-violent sit-ins and marches. People died in the struggle; King felt the burden of those deaths and sensed the ambiguities of his own power. He was ambivalent about the social unrest he and the movement unleashed, but believed it was worth it to achieve justice. I see in King a combination of Rauschenbusch and Niebuhr. His high idealism and non-violent activism was partly inspired by Rauschenbusch and the Social Gospel; his realism and willingness to use power for confrontation risking conflict for the sake of justice was partly inspired by Niebuhr.

What advice would Niebuhr give to the Machine Gun Preacher? I think he would congratulate him for daring to get involved in a bloody, messy struggle to save children’s lives but warn him against over use of violence, against vengeance, and against ever believing his cause is wholly righteous and without sin. He would urge him to use only what deadly force was absolutely necessary to save the lives of innocent children and to never think of himself as innocent. He would advise him to seek God’s forgiveness for being involved in violence even though it was thrust upon him and he had little choice given the circumstances. He would remind him that this is a broken world and there is no perfection and violence is always a sign of that brokenness, even when it is necessary. He would tell him to “sin boldly and repent more boldly still.”

Now I turn to Gustavo Gutierrez and liberation theology. Popular North American and especially conservative Christian images of liberation theology are distorted. Gutierrez, the “father of liberation theology,” is not a pacifist but draws back from endorsing violence even in the most just causes. He prefers non-violent approaches to social justice which he defines as equality of opportunity for all people regardless of social class or race or gender. Violence he believes is only justified when it is a response to the unjust “institutionalized violence” of the oppressors—the “first violence” that calls forth the “second violence” of the oppressed to liberate themselves from dehumanizing uses of power, domination and control. Many people in North America celebrate Independence Day, the Fourth of July, even in church but condemn other oppressed people’s revolutions—even when they are against military dictatorships that use death squads to murder non-violent dissenters such as Jesuit priests and nuns.

Gutierrez, like Rauschenbusch and Niebuhr, is driven by the vision of Shalom—peace, justice and prosperity for all. In A Theology of Liberation he urges utopianism—a vision of just such a Kingdom of God on earth—as a means of social progress towards equality. However, what he adds to Rauschenbusch and Niebuhr, although it may be implicit in them, is the principle of “preferential option for the poor.” Christian love, he argues, requires solidarity with the poor and by “poor” he does not just mean materially poor; he means powerless. For Gutierrez, justice is what happens when the poor are lifted up and empowered to live self-determining, human lives—lives where they have opportunity to achieve at least a modicum of their human potential.

Again, I see a hybrid of Rauschenbusch and Niebuhr in Gutierrez. I’m not arguing that he consciously, intentionally combined them although there is evidence that he read both. He was more influenced by the “political theology” of European theologians Joannes Metz and Jürgen Moltmann. However, there are echoes of both Rauschenbusch and Niebuhr in Gutierrez’s liberation theology.

In complete congeniality with Rauschenbusch Gutierrez regards the poor as special objects of Christian love. Also, with Rauschenbusch the Peruvian theologian is unapologetically utopian—calling Christians especially to hope and plan for the Kingdom of God on earth and to settle for nothing less than peace, prosperity and justice for all. But he goes beyond Rauschenbusch in seeing differentiating wealth as always a sign of the brokenness of this world. And he agrees with Niebuhr that Christian use of political power, even violence, is sometimes necessary to move a society closer to justice. Where he disagrees with Niebuhr, however, is in regarding the conflict and social unrest necessary to establish justice as sinful and requiring repentance. While he doesn’t regard it as something to celebrate, neither does he think the appropriate response to the overthrow of an oppressive regime is sackcloth and ashes.

Gutierrez’s is a social ethic for revolutionaries. Not necessarily for guerilla fighters (he urged his friend Camillo Torres not to join a group of guerillas) but for Christians and others who are impatient with the slow pace of justice and feel called to enter into the conflicts of history on the side of the oppressed.

Ironically, many people who hold up Dietrich Bonhoeffer as a saint and martyr criticize liberation theology. I think Gutierrez would remind them that the German pastor and theologian joined a revolutionary cell and volunteered to pull the trigger on Hitler. They turned him down and used him in other ways, but he knew he was complicit in their plot and that the blood of Hitler and anyone else who might be killed in the coup would be on his hands as much as on anyone’s.[1]

Now, because some question this, I want to diverge from the main line of my talk for a moment and insert a “side bar” about Bonhoeffer and violence.

According to his student and biographer Eberhard Bethge Bonhoeffer asked, paraphrasing here, what is the duty of a Christian who sees a madman driving a car into a crowd of people? To go behind the car picking up the wounded and giving them first aid? Or, if possible, to get the madman out from behind the wheel of the car?

Some fans of Bonhoeffer have recently questioned whether the German pastor, committed to pacifism as he was, really became involved in a plot to kill Hitler. Mennonite theologian Mark Thiessen Nation and two scholars recently published a book entitled Bonhoeffer the Assassin? with the thesis that the author of The Cost of Discipleship and Ethics did not participate in any conspiracy involving assassination. However, this is flatly contradicted, as they admit, by Bethge. Bethge leaves no doubt about Bonhoeffer’s knowledge of and support for the plot to kill Hitler. However, this was, he says, a “boundary situation,” not a matter of principle.

Bethge reports that as early as 1932 Bonhoeffer hinted at the future and what it might require of Christians. In a sermon preached that year the German pastor-theologian suggested that “times would come again when martyrdom would be called for.”[2] Speaking prophetically, Bonhoeffer said about the coming martyrdoms that “this blood…will not be so innocent and clear as that of the first who testified. On our blood a great guilt would lie: that of the useless servant who is cast into the outer darkness.”[3] This is a hard saying, but Bonhoeffer left us many hard sayings to reflect on. Bethge clearly interpreted it as meaning not that the new martyrs would go to hell but that they could not count on innocence in necessity. Bethge, a theologian in his own right, recorded about Bonhoeffer’s decision to join the conspiracy against Hitler, which he knew very well included a plot to kill the dictator, “Thus, the ‘boundary situation’ led Bonhoeffer to abandon all outward and inward security. By entering into that kind of conspiracy, he forsook command, applause, and commonly held opinion.”[4]

End of Bonhoeffer side bar and back to the main body of my talk.

So what would Gutierrez’s advice be to the Machine Gun Preacher? Well, that’s fairly obvious: Use only deadly force that is absolutely necessary to stop the Lord’s Resistance Army from carrying out its maniacal slaughtering of entire villages and kidnapping and murdering of innocent children. Don’t rejoice in the bloodshed, but don’t feel guilty about it, either. Do what you have to do out of love—for the innocents and for those who are threatening them.

Finally I come to the real purpose of this talk—the Yoder-Hauerwas challenge to all of the above—to Rauschenbusch, Niebuhr and Gutierrez.

Over the past two to three decades numerous well-intentioned, smart, caring and thoughtful young Christians have jumped on the Yoder-Hauerwas pacifist, perfectionist bandwagon and reminded all of us that obedience to Jesus is the first principle of social ethics and that the church is not a launching pad for social revolution but the city set on a hill to show the world its true self and the better way of life God wants for it.

Perhaps the Yoder-Hauerwas approach is best summed up in the Duke Divinity School theologian’s phrase that “the church is the Christian’s social ethic.”

Jesus did not come to overthrow unjust, even oppressive social systems; he came to establish an alternative social order within this broken world. The focus of Christian social ethics should not be on reform or revolution of the world but on being the church as God intends it to be following the Kingdom principles of Shalom laid out in the Sermon on the Mount.

Christians who become involved in social struggles using political power, coercion and deadly force are usurping God’s role; God has not called us, his people, to be managers of history but to leave that to him and organize ourselves in the “upside down Kingdom” of Jesus. Within the church love and justice are never forced into opposition or even dialectic; obedience does not have to be sacrificed for effectiveness. The church, as the “community of the beloved” can change the world through example, if God uses it for that purpose. But that is ultimately up to him; we are only called to be that community. Yes, to be sure, we can speak truth to power from within it. Or, better put, the community of Christ can speak truth prophetically to power. But Christians, individually or organizationally, must not take up the reigns of worldly power to attempt to bring in the Kingdom of God using ungodly means. “Sin boldly” is the path to perdition; compromise with evil is the door to disobedience and ultimately dissolution—of God’s plan and purpose for the church.

For Christians, according to Yoder and Hauerwas, the cross unites love and justice. That’s true of Jesus’s cross and ours. Self-sacrificial service and voluntary subordination are the way to the Shalom Jesus revealed.

The Yoder-Hauerwas social ethic is one for perfectionists. And I don’t mean that in a pejorative way; it’s a social ethic for Christians with high ideals and determination to be obedient to the way of Jesus even if that requires ineffectiveness in worldly terms. It is a social ethic for those who really believe in the brokenness of the world and trust God to heal it, if he chooses, using the church’s wholeness as a witness to his healing power.

Yoder and Hauerwas and their followers target especially Niebuhr for his alleged compromises with worldly power and for leading his followers down the primrose path away from Jesus and toward Constantine. Niebuhr, of course, were he here to argue with Hauerwas, would no doubt respond that the path he trod did not lead toward Constantine or away from Jesus but toward a better, more just world and away from withdrawal and abdication of responsibility. And so the argument goes on—between the Yoder-Hauerwasians and the Niebuhrians today.

What advice would Yoder and Hauerwas give to the Machine Gun preacher? Well, that also, as in the case of Gutierrez, seems fairly obvious: Put down your machine gun and other weapons and work with the churches of the Sudan and Uganda and America and elsewhere to provide a safe sanctuary for victims of violence and oppression. And prepare to die just as Jesus did. The servant is not greater than his master and should not use means his master would not use.

I began by admitting my own cognitive dissonance when reading these theologians and social ethicists. I agree with all of them! And I disagree with all of them! While reading Rauschenbusch I find myself inspired and energized to go forth and reform the world using persuasion and pressure with Shalom always in view as the goal. While reading Niebuhr I find myself comforted and encouraged to rely wholly on God’s grace, mercy and forgiveness when I must fall short of the high and perhaps impossible standards set by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount. And in Niebuhr I find a realistic account of the world and a ringing call to responsibility for it. While reading Gutierrez I find myself fired up to fight for the poor, the powerless and the oppressed, to go forth into the halls of power prophetically to challenge the privileged and the systems that support them and keep the disadvantaged pressed down. While reading Yoder and Hauerwas I find myself called to commitment to the church of Jesus Christ and to work together with others of like mind to make it the locus of Shalom in this broken world, to help it be the witness Jesus was to those around him of God’s love and mercy and transforming power. Also to make it a sanctuary for the helpless, hurting and oppressed.

From Rauschenbusch I receive the vision of a human fraternity of equals organized according to loving service without domination or oppression. From Niebuhr I receive the realism of the inevitability of sin even within Christian community and the call to social transformation without illusions of righteousness. From Gutierrez I receive the ideal of the preferential option for the poor and the call to solidarity with them. From Yoder and Hauerwas I receive the reminder that the church is my main social ethic and to avoid all triumphalism including especially Constantinianism.

So where to go from there? Where do I come down and what advice do I give—with regard to those areas of incommensurability between these four approaches to Christian social ethics? While there is no perfect hybrid of all four, I do think they are capable of combination with adjustments none of them would want. But here goes, anyway.

First, I agree with Yoder and Hauerwas that the church is the Christian’s primary social ethic. Our first duty, calling, is to help the church be the witness of Shalom to the world God intends it to be. But that means investing primary interest and energy in it. And it means avoiding all entanglements of the church with the state after the Constantinian pattern. The church is not called to be a launching pad for revolution but a community of love, the community of the beloved. The church should never take up arms for any cause; the church is the family of God, dysfunctional as it is in its own brokenness, that lives from self-sacrificial service each to every other.

Second, however, I agree with Niebuhr and Gutierrez that Christians, that I, must be open to the call of God to take up power, even deadly force if necessary, to defend the weak, the helpless and oppressed. With Niebuhr I agree that such use of coercive force for any cause is less than perfect, is even sinful, and never something to be celebrated or boasted of. With them I agree that Christians should not abandon government to pagans but lovingly, for the sake of the poor, the powerless and the oppressed, risk sinning boldly by daring to get involved in the messy world of secular statescraft shaping public policy and, even occasionally, fighting for the lives and rights of especially the helpless.

John Stackhouse, an evangelical theologian at Regent College in Vancouver, Canada, expresses this sentiment very articulately in his book Making the Best of It: Following Christ in the Real World:

Most of the time…we know what to do and must simply do it. Sometimes, however, the politician has to hold his nose and make a deal. The chaplain has to encourage his fellow soldiers in a war he deeply regrets. The professor has to teach fairly a theory or philosophy she doesn’t think is true. The police officer has to subdue a criminal with deadly force. We are on a slippery slope indeed—and one shrouded in darkness, with the ground not only slippery but shifting under our feet. So we hold on to God’s hand, and each other’s, and make the best of it. (288)

Whenever I am tempted too strongly toward the Yoder-Hauerwas ethic of love perfectionism, absolute non-violence, including refusal of all coercion and force, I think of the Christian abolitionists of the first half of the nineteenth century. William Wilberforce accomplished much good by arguing forcefully, with much political negotiation and more than a little pressure in the House of Commons, for abolition of the slave trade. In America many Christians, including revivalist Charles Finney and his Oberlin students, practiced civil disobedience and even occasionally violence to rescue slaves from bondage and help them escape to Canada along the “underground railroad.”

For African slaves Shalom meant freedom from kidnapping, bondage, torture, family separation, degradation of their humanity. For those who dared to take up the reigns of power to fight for their Shalom it meant sinning boldly by political compromise, sometimes deceit and subterfuge, civil disobedience and even occasionally open rebellion against unjust laws.

Who is to say that’s all in the past and now we can settle back comfortably in our Christian communities and disengage from the struggles for justice that still surround us?

With great reluctance and admission that repentance is called for, were I in the Machine Gun Preacher’s shoes I hope I would have the courage to do the same as he. And I hope I would remember that even such a just cause is fraught with ambiguity and unrighteousness and requires grace, mercy and forgiveness.

Nineteenth century theologian-pastor Theodore Parker first said “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” I am here arguing that sometimes we have to help it bend. May God grant us the courage, faith, humility and repentant hearts as we take the risk of helping it bend.