If you’re a Catholic, you take your guilt to confession. Here’s a confession for you: I shamelessly read the Twilight series—and I’m sure I liked it too much.

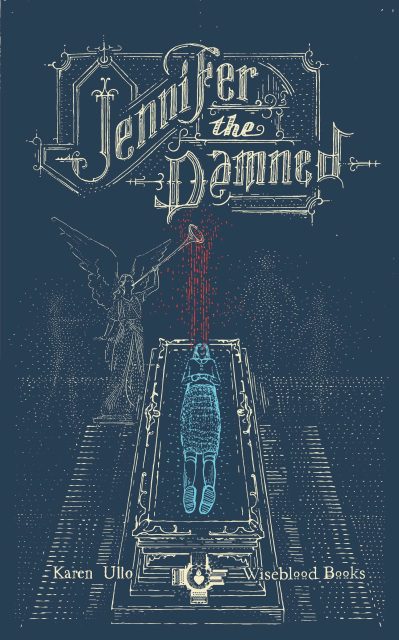

Karen Ullo’s new novel, Jennifer the Damned (Wiseblood Books, 2017) successfully navigates the teen vampire genre towards Catholicism: Jennifer is a teenaged vampire who kills against her will, who wants to love, but can’t, and hopes, regardless, that God can love her, somehow.

Reading her story, I couldn’t help but think of the Biblical Samson and John Milton’s Lucifer.

Samson did God’s work and was a bad guy. An anti-hero. He drank, broke the rules, and killed. But he was still a Judge and appointed man of God. An agent of God. And that’s what I see in Jennifer.

When she kills a boy besides the theatre, she ruminates:

“He gulped the hot, wet summer air and threw his arm around my head, pulling me still further in, rapture measured by the fathom, our bodies turned to wind. As the last impassioned drops of life gurgled past my tongue, the boy who smelled of stardust groaned and smiled. Surely, if I could offer any goodness in this world, this was it. I could make the dark absolute death arrive bathed in astral light.”

If she must kill she will bring death as a gift. The gift is the passage, the portal, the sweetness. It is a wonder that Providence didn’t bring it about. An agent of God, bearing a passage toward beatific eternity. The boy dies in a spiritual, joyful, no, beyond that–an elated, quasi-orgasmic perfection–and gives his ghost to the soul eater. A worker of God.

Like the angel of death, Jennifer gives infinity, while serving her normality.

And yet, she feels the guilt. A Catholic guilt. A Christian guilt. A Crime and Punishment type of guilt. A guilt that hurts, and the reader feels it too.

The supernatural in Ullo’s novel is not vampirism–it’s the conviction of sin. Vampires kill. In the world of the novel, that’s natural. But Jennifer’s Catholicism makes her more than a monster bent unremittingly towards death.

Jennifer tries to fight the good fight, carry her cross. Like Milton’s Lucifer, a fallen angel angry at his fate, hopeful to change eternity, angry at God. Desperate for hope. But unlike Milton’s Lucifer, Jennifer had no choice in her damnation. In Jennifer, Ullo negates the concept free will.

What a terrible life, to inevitably do who you hate. In hell, I imagine that the damned locked the doors from the inside. Souls remain there because they hate God, because it is their nature, it’s their pain. But Jennifer doesn’t choose hell. She never had a choice.

Helen, her pseudo-mother, vampire-maker, kidnapper, is the classic, hellish vampire. Creating. Hating. Against all that is good. Bitter, no chance in heaven for her. Helens tells Jen: “I put you in Catholic school for a reason, Jen. I wanted you to know the truth. I wanted you to see how cruel God is.”

Jennifer imagines her soul, brushed free of wrinkles by Mother Celeste in her Catholic school, “dangling … like laundry from Gabriel’s bright horn. It hung there, taunting, just above my reach…”

And it breaks her; she throws her convictions to the wind and moves to L.A. (of course). Yet she never gives up hope for hope itself.

Ullo also mentions Alcoholics Anonymous a couple of times in the narrative, comparing Jen’s drinking of souls to an addiction. Yes–drinking souls. She tries to drink a dog’s blood, but no go—to satisfy the vampire, the victim must have a soul. The soul makes the blood good.

Ullo’s respect for the purity and authenticity of life–and its blood source–is deeply Catholic. Jennifer’s understanding of the value of life is another marker of her Catholicism. She kills and hates it. Later. After the high, after she clears the “cement from her lungs” and drinks what is her substance.

Jennifer the Damned is a Byronic hero, a type of Prometheus, and Frankenstein–but she is, most importantly, in this narrative–a devout Catholic. And not by practice, either, but by an irrevocable part of her identity.

So Ullo gives us a horror novel, with a vampire that wants humanity, yes, but even more important, wants the infinite life and death of Christ. A vampire who wants to be a Catholic.

Read this book if you like vampires, yes, and read it if you like romance mixed with vampires, romance, or just straight up horror. But also read it if you love life, and have known guilt—Our Catholic guilt—Christian guilt. Ullo knows there is such a thing as a holy guilt.

Treasured, and ever waking.

Jonas Perez is the author of Finibus and a musician. He lives in Arlington, TX, with his wife and children. He is a parishioner at St. Patricks Cathedral in Downtown Fort Worth.