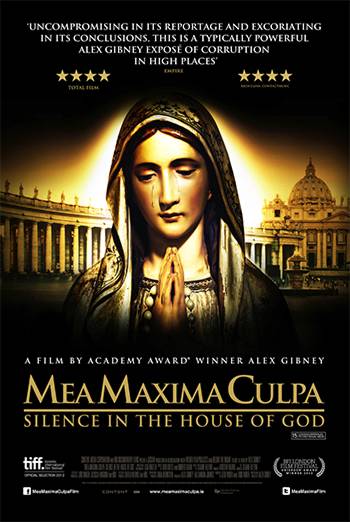

The following is a statement about this HBO film from SIGNIS, the World Catholic Association for Communication. Australian Sacred Heart Missionary, Rev. Peter Malone, gives a detailed review with additional information. The film, by award-winning director Alex Gibney, already aired on HBO in the US (and can be seen on HBOGo or on reruns).

MEA MAXIMA CULPA: SILENCE IN THE HOUSE OF GOD.

13th March 2013

Clerical sexual abuse in the Catholic Church has been a public focus for more than twenty years in some countries. Victims have been exploited by predators. Ways for seeking and finding justice have been difficult. Church authorities have had to face the charges, the recriminations, the failures in leadership. All Catholics have had to share the shame. And sexual abuse is not something that will pass from world attention in the near future.

This statement is being written on March 13th. The Cardinals went into the conclave yesterday. We will soon know who the successor to Benedict XVI will be and what will be the directions for the Church in the coming years. Hopes have been expressed and many predictions. But we do not know. This film can serve as a summary of the state of the question up till now – though filming was completed in 2011 and the film released in November 2012 in the US. It did not anticipate the resignation of Benedict XVI, but the situation would have been the same had the Pope died in office.

[The conclave was briefer than anticipated. Francis was elected in the afternoon of 13th March in Rome. Only speculations at this time.]

But, there is a major difference in 2013. The Cardinals, in this world of instant communication and social media, are aware of the needs of victims and of the scandals. They had a week of discussions before entering the conclave without any emotional burdens of mourning a dead pope. Audiences who see this film may well think that it would have been beneficial for the Cardinals to have attended a screening. It serves as an aid to examination of conscience as well as an effective summary interpretation of the history of 20th centuryabuse and into the 21st century, starting from an American story of the 1960s on, moving more nationally, then internationally, an outline of the way that bishops handled cases as well as how the Vatican bureaucracy dealt or did not deal with cases, requests and civil and canon law.

It needs to be said that this is a very well-made film. Audiences will not agree with all the speakers or the expert ‘talking heads’. After all, the film marshals facts but, an is any film, it is an interpretation. The American writer-director, Alex Gibney, has very good credentials. He made the surprising an alarming Enron: the Smartest Guys in the Room (quite an expose) as well as winning an Oscar for Best documentary for another expose, this time torture in Afghanistan and Iraq, Taxi to the Darkside. Expose is his forte.

MILWAUKEE AND FR LAWRENCE MURPHY

As with any successful film, the maker wants to draw the audience in. And that is what happens here. We are informed briefly about the woeful abuse career of Milwaukee priest, Lawrence Murphy. He is the offender for the first third of the film. But, the film is victim-focused, all the more emotionally telling here because we see men in their fifties and watch them tell their stories – ‘watch’ advisedly, because the men are deaf and sign their stories, vividly and powerfully, while some articulate Hollywood actors speak their signed words. They are silent men in a house of God

Fr Lawrence Murphy, ordained in 1950, was a popular, outgoing figure, fund raiser for the school for the deaf which he eventually ran for many years.

The stories of the men are told plainly, factually, especially of their childhood and family backgrounds. Some parents could not sign which put the boys at a great disadvantage, silenced in many ways, in letting their parents know about the molestation. The stories are also told visually with many excerpts from home movies of the period, of the boys and their life at the school and of Fr Murphy himself. Which means greater repugnance towards the abuse from us the audience, especially with staged scenes in church, confessional and dormitories. We are not just hearing a story of someone we don’t know. We can see him and wonder how he could behave in such a destructive way.

The complaints and testimony are clear, detailed and, though some at the time could not believe the boys or such stories about a priest, undeniable. We hear their response to persistent abuse, some feeling elated at first of being singled out and special, then their shock at experiences in confession and in Fr Murphy’s room and holiday house. And some resigning themselves to this fate.

The film moves on to their attempts to let others know what had happened to them, not heard at first. Or, heard, and not believed or believed and nothing done. It is pointed out that they lived in a time of protest and activism and this influenced their attempts to make their cases heard – including distributing posters in streets or outside church, denouncing Fr Murphy as an abuser. Evidence is shown that official complaints about Fr Murphy were made to the Apostolic Delegate in 1974.

EXPERT COMMENTATORS

That first section of the film was called ‘Lambs of God’. The next section introduces the veteran of studies of clerical celibacy, with interviews of priests over the decades, Richard Sipe. A former Benedictine, Sipe has written extensively. His introduction at this stage of the film enables him to offer something of the history of celibacy, deficiencies in formation of priests, the consequences of this as well as the loneliness in the celibate vocation. The selection of sequences with Sipe is judiciously chosen and makes a great deal of sense (while not saying everything, as many would point out). Other experts seen in the film include another former Benedictine, Patrick Wall, who had a mission of moving around examining cases but who ultimately found it, and his perceptions of covering priests, too much and so left the priesthood but continued advocacy for victims.

The passionate Fr Tom Doyle, the American Dominican and canon lawyer who has been constant in his work for victims (and now, perhaps, feeling justified in his perseverance of cases and issues, especially in the context of law and Canon Law) has a great deal to say about cases, about the loyal impulses of priests, bishops and devout laity who have felt that they must protect the church at all cost.

There are some interesting sub-plots, so to speak, which enhance the quality of the film and its research. The story of Fr Gerald Fitzgerald and his founding of the Servants of the Paracletes in the 1940s, an order to work with priest sexual offenders as well as priest alcoholics. He advocated spiritual reform rather than psychology, but he and his order are praised for recognizing and acknowledging the problems an dwanting the priests out of and away from ministry.

The other sub-plot concerns the career of money-raiser, founder of the Legionaries of Christ, Fr Macial Maciel, confidante of Cardinals and Popes, who was a Jeckyll and Hyde perpetrator of sex crimes and injustices. His story, well-illustrated in terms of clerical patronage, is told in the context of John Paul II (who favoured him) and Benedict XVI (who ultimately dismissed him to a life of prayer and penance, though beachfront footage of Jacksonville, Florida, is shown where he retired to a home for priests and died).

TO BOSTON, TO IRELAND

From Wisconsin, the second third of the film moves to Boston and the 2002 uncovering of scandals, with the arrests and gaoling of Frs Geoghan and Shanley, the resignation of Cardinal Law (with adverse comments on his leadership in handling cases in Boston) and his comfortable career and life in Rome. From there, the film oves to Ireland (the film does have some Irish finance in it), the case in focus being that of Fr Tony Walsh, a singing priest with a popular reputation, in denial of his abuse at first, then admitting it but not being defrocked until almost 20 years after the first reports.

We all need to be media savvy, knowing what we want to say and saying it, without ambiguity or leaving ourselves open to misinterpretation or ridicule. There is a terrible moment in an interview with Cardinal Desmond Connell of Dublin (who is later shown as having made some effort, though belatedly, in contacting Rome about cases). He is asked if it would have been good for him to have visited victims. He does admit it would, but, unfortunately, for himself and his reputation, he adds, even with traces of a smile, that he did have many things to do.

At different stages during the film, opinions are given as well as questions raised as to how anyone could commit such crimes. Some technical language is used, quite enlightening and suggesting further reflection.

‘NOBLE CAUSE CORRUPTION’

‘Noble cause corruption’ is one contribution, the perpetrator’s belief in his own goodness. There are later quotations from Fr Murphy stating that his behaviour was trying to help the boys, some with sexual orientation difficulties, that he behaved as he did to help some boys through sexual confusion, that he recognised their needs, even taking their sins on himself – and that he prayed and confessed afterwards. There was also mention of ‘cognitive distortion’ in the way that the abuser interpreted his behaviour. On the other hand, one of the men remembers an occasion in the dormitory, a crucifix nearby, ‘There was Jesus on the cross, dying with a broken heart’ and not helping him.

The only other member of the clergy to be interviewed for the film besides Fr Doyle is Rembert Weakland, former archbishop of Milwaukee, who talks frankly and with sorrow and shame about events in his own life (nothing to do with abuse of minors) and who, when asked had he met Fr Murphy, replied that the main impression he had was that Murphy was childlike in his self-delusions.

VATICAN ISSUES

The film does return to the men of Milwaukee and their attempts to make their case heard, including relying on their lawyer, Jeff Anderson, the man who took out applications to sue the Pope, Cardinal Bertone and Cardinal Sodano who, by this stage of the film, does not look good at all, especially in his espousal of the cause of Fr Maciel and receiving his large donations, but who became notorious when he referred in a speech to the Pope about the sex abuse scandals as media ‘gossip’. (This scene is included.)

But, in the latter third of the film, the focus is well and truly on Rome. One of the difficulties is the film’s constant referring to ‘The Vatican’. While the references to the Pope and the Curia are accurate in their way, it is particular people in the Vatican and its bureaucracy who are responsible. The whole section will be fascinating to many Catholics but may be too general or taking us into unfamiliar realms which may make it rather difficult for some non-Catholic audiences.

Here is where the investigative journalism can be hard work. The film tries to give some dates for letters coming to the Office of Doctrine of the Faith, of Cardinal Ratzinger’s decisions that all cases come to him which, as the narrator suggests, makes him the most informed person in the world on this abuse. Dates are given as are examples of letters sent and not answered, or material returned to sender as unwanted.

The continual accusation is the slowness of authorities to reply, to act, to sanction. There is the difference in ideology in the past that abuse was a sin, and therefore to be repented of and forgiven, rather than a crime. Even in English-speaking countries which Rome thought were the only countries where this kind of abuse really took place, it was only in the 1990s that most realised or were informed that this sexual abuse of minors was a crime, police matter. Without in any way undermining the seriousness of the crimes, we can see that nowadays a lot of anger comes from assuming that what we know now was known clearly then and not acted on. (In Australia, this will come up in the Royal Commission into non-governmental organisations. Recent accusations of harassment and abuse in the Australian Defence Forces have been met with the now familiar defensive statements by authorities, the same with the BBC heads and their comments on the sexual predation of British TV personality, Jimmy Saville).

It is in this section, that the film-makers offer many talking heads for our consideration: Robert Mickens, correspondent for The Tablet, Laurie Goodstein from the New York Times, Marco Politi, an Italian Vatican expert, human rights lawyer, Geoffrey Robertson who believes the Vatican should be sued and that it is not really a country. There is also an excerpt from a TV interview with William Donoghue, the loudly aggressive head of the Catholic League in the United States. Pope John Paul, like many a bishop, may have initially disbelieved that such behaviour could occur. Pope Benedict had so much data (the story of his sending a member of his office to the US to collect the data on Fr Maciel on the evening of John Paul’s death makes for interesting viewing) but delayed in acting on it.

A television excerpt where he says he is shocked that priests could behave like this is noted as indicating how he thought about priests and the dignity of priesthood first rather than the victims. However, there is another excerpt from him where he does put the victims first. (This may have come from his meeting with victims on his visits to the US, Australia and other countries, something which is not mentioned in the film.)

[One secular reviewer called out as he left the film, ‘All I know is that Ratzinger’s to blame’. While allotting blame, that is not exactly the nuanced response to the film. A source for gauging some reaction to the film is checking the entry for the film on the Internet Movie Database, IMDb. Up to now, the reactions are strongly anti-Church, one stating,

I’ve gradually come to see the Catholic Church for what it truly is — an archaic, oppressive, lying institution that’s hopelessly out of touch with 21st Century realities, which destroys millions of lives around the world and has done unspeakable evil throughout human history.

The excesses stem not just a few bad apples. The root cause is institutional corruption. In Catholicism, according to Canon Law, everything flows downward from the very top. This means the Vatican ultimately bears responsibility for crimes against humanity.]

2011…

At the end we go back to Milwaukee. We see the men signing again, ‘Deaf Power!’. We see their desperation, their being acknowledged (after some scenes with Archbishop Cousins of Milwaukee in the 1970s whose response was erratic, inclined not to believe such stories about a priest, meeting with Fr Murphy rather than asking any of the other students and sending a nun (name and photo supplied in the film) to get one of the men to recant his statement and make an apology to the archdiocese). One writes a letter to Cardinal Sodano, telling his story, asking for Fr Murphy to be stood down, noting that he is still allowed to receive communion when others who are far less guilty are forbidden. Two of them went to see Fr Murphy before he died in 1998, with a camera, but he told them to go away, that he was an old man and wanted to live in dignity. He seems to have gone out, nevertheless, to play poker machines and collapsed, and was buried in vestments as a priest. But, the men are alive, relieved and, still in the spirit of activism, American style, protesting, even if what happened, as one commentator says, was an amazing outpouring of sadness.

Fr Doyle reminds us that the emphasis on the priest as sacred at this juncture is not helpful, nor is the loyal, traditional ‘Catholic mindset’. Archbishop Weakland adds that there has been a long held belief in the Perfect Church – and the sooner that is forgotten, the better.

So, in 2012-2013, here is a film that summarizes much of the history of abuse and how it was handled and mishandled or not handled. It will be released in many territories after the election of the new Pope.

Catholics and faith. Someone remarks in the film that many have lost faith in the hierarchical church – but that they have not lost their faith.

Note:

For reference, the main films produced and widely distributed – not the many current affairs and documentary films for television – on the sexual abuse of male minors, the particular focus of Silence in the House of God – include:

1990, Judgment, US, with Keith Carradine, Blythe Danner, David Strathairn

1996, Pianese Nuzio, Italy, with Fabio Bentivoglio

2002, Song for a Raggy Boy, Ireland, with Patrick Bergin, Aidan Quinn

2004, Mal Educacion, Spain, with Gael Garcia Bernal

2005, Our Fathers, US, with Christopher Plummer, Brian Dennehy, Ted Danson

2006, Primal Fear, with Richard Gere, Edward Norton

2006, Deliver Us from Evil, documentary, director Amy Berg

2008, The Least of These, with Isiah Washington

2008, Doubt, with Meryl Streep, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Adams

Peter Malone MSC

Melbourne