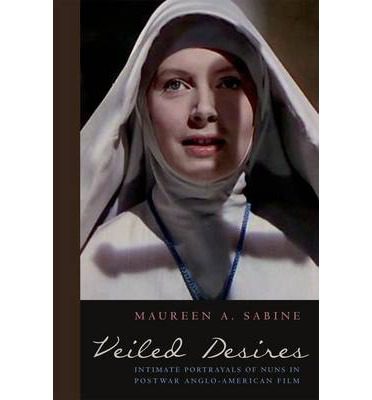

VEILED DESIRES: INTIMATE PORTRAYALS OF NUNS IN POSTWAR ANGLO-AMERICAN FILM

By Maureen A. Sabine

Published by Fordham University Press, $30

Sometimes there can be a sacramental quality about cinema. When movies tell stories well, they become outward manifestations that transcend the inner realities of their characters in ways that touch the audience. Maureen Sabine has written a masterful book that reveals the sacramentality of cinema about religious women. She is confident of her topic and her analysis, and has found something worth saying even about films that I don’t care for very much.

In the author’s own words, Veiled Desires: Intimate Portrayals of Nuns in Postwar Anglo-American Film aims “to change the way nuns are seen onscreen by probing the stereotypes in which they have been immured and by considering how these women religious figures came to capture the popular imagination.”

I am not sure she has succeeded in changing the way nuns are seen on screen, as this will depend on the viewer taking the time to tussle with the dominance of kitsch and stereotyping of nuns in the general culture. In addition, appreciating this book will require as much intentionality as the author has given her subject in order to consider the many ideas, layered analysis, interpretations and conclusions in this intriguing tome — while savoring it at the same time.

Sabine, a history professor at the University of Hong Kong, knows her cinematic sisters intimately. She understands, though she does not articulate until deep into the book, that all of the films she deals with have been “shaped by the vision of male directors” and some scenes suggest the “male enchantment with the mystique of the cloister.”

The key films about sisters that Sabine chose for her thesis are:

- “The Bells of St. Mary” (1945);

- “Black Narcissus” (1947);

- “Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison” (1957);

- “Sea Wife” (1957);

- “The Nun’s Story” (1959);

- “The Sound of Music” (1965);

- “Change of Habit (1969);

- “In This House of Brede” (1975);

- “Agnes of God” (1985);

- “Dead Man Walking” (1995);

- “The Magdalene Sisters” (2002);

- “Doubt” (2008).

Then the author brings in films that at first glance seem to have nothing to do with sisters but serve to contrast the themes of her book, especially the dualism, tension and fecundity of eros and agape at work in the lives of cinema sisters as well as in real life. These films are:

- “Casablanca” (1942);

- “The Keys of the Kingdom” (1944);

- “The Inn of the Sixth Happiness” (1958).

Eros and agape form the most important lens pairing that frames her analysis. She uses Audre Lorde’s definition of eros as a life force, “the core longings that make us most fully human: for fulfilling work, for the creation and celebration of beauty, for intellectual and spiritual pursuits, for the enjoyment of friendship, love, connection, and intimacy. … A life force that stands in opposition to dehumanizing pornography.” The author turns to Anders Nygren for a description of agape as a loving and “wholehearted surrender to God,” an unconditional obedience, given without reservation, and a “conversion or change of heart” in which God awakens love in the person.

Thus, Sabine’s point of departure for her analysis is the nun as a whole person …. CLICK HERE to continue reading at the National Catholic Reporter