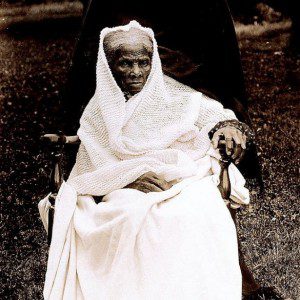

Harriet Tubman was Robin Hood. She was an outlaw and a thief who stole from the rich and gave to the poor.

Later in life, after the law had been changed and the Constitution rewritten, Tubman was praised and honored as a hero and a humanitarian — and for being the first civilian woman to plan and lead a (massively successful) combat operation by the U.S. military. But make no mistake, during her years as a “conductor on the Underground Railroad,” Harriet Tubman was a thief who regularly stole the property of wealthy Maryland farmers. That was what the law said and what the Constitution said. She broke that law and took “property” that didn’t belong to her. We may not think of this as theft today because the “property” she stole was people — human beings, but the law at the time did not recognize those people to be people. The Constitution said they were property. And that made her, legally, a thief.*

As Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote last year, “The fact is that for most of our history, every black person who’s ever actively resisted was effectively committing a criminal act. Harriet Tubman might grace postage stamps today, but in her time she was a criminal who likely would have been executed or sold South had she been caught.”

Part of what is so awesome and inspiring about Harriet Tubman, of course, is that she never was caught — and not for lack of trying.

Now this legendary outlaw and spy might just wind up on the $20 bill.

The Quixotic campaign to put Harriet Tubman on the twenty has been kicking around for decades. I’ve written about it several times here over the years (and even earlier, in Prism magazine), but always in a pipe-dreamy, wouldn’t-it-be-cool kind of way, with no expectation that this was something that could actually happen.

I first encountered the idea from an unlikely source — a George Will column from the early 1990s in which the conservative commentator recommended ditching all of the presidents from American currency and replacing them with cultural figures. (I can’t find the original column and I don’t remember all of Will’s playful suggestions, but I think he wanted Louis Armstrong for the $1 bill and I still second that motion.)

Putting Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill is appealing because it addresses four different problems at the same time: 1) Andrew Jackson was a murderous jerk who contemptuously violated his oath to defend the Constitution and he shouldn’t be honored with a place on our currency; 2) no American bills have women on them; 3) no American bills have people of color on them; and 4) Harriet Tubman was just incredibly awesome and we can’t say that often enough.

The current push is being led by the group Women on 20s, which just conducted an online poll to choose which great American woman to honor on our national currency. (Tubman narrowly earned more votes than the runner-up, Eleanor Roosevelt.) And now Women on 20s is presenting a petition to the White House, requesting the treasury secretary to make the change.

Sierra Mannie, Kirsten West Savali, and Jay Smooth all offer thoughtful, powerful, cautionary commentary about the limited benefits and potential downsides to this kind of symbolic gesture. If — and it’s still very much a long-shot, unlikely if — Harriet Tubman does wind up gracing the $20 bill, that symbolic gesture will likely be misrepresented and abused in the same way that the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday is routinely misused to try to neutralize and inoculate against everything that King did and said and fought for.

But that would be true of King’s legacy even if we didn’t have that national holiday. Those who want to usurp and undermine that legacy by honoring him as a symbol and ignoring his substance will always find and create ways to do so. We should never mistake the aspiration of the symbolic honor for the achievement of the substantial outcome, but I still think we’re better off having that symbol than not.

This concern reminds me a bit of hearing all the talk in 2008 of how the election of the first black president would lead to or somehow prove that America had entered a “post-racial” utopia. It was already clear, long before election day, that an Obama victory would be exploited and misused to challenge the necessity of fundamental civil rights laws and protections — as, indeed, it was, reprehensibly, in the indefensible Shelby County ruling of the Roberts court. But even so, I don’t think that amounted to a reason not to vote for Obama.

In any case, whether or not Harriet Tubman ever winds up on the $20 bill, I still definitely want to see a big-budget, major-release Hollywood movie telling the story of the Raid at Combahee Ferry. With Viola Davis, please.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* Harriet Tubman was also a Christian and, of course, many streams of Christian tradition condemn theft and law-breaking as a grievous sin without exception. Those Christians will cite Romans 13 (“Let every person be subject to the governing authorities; for there is no authority except from God, and those authorities that exist have been instituted by God”) and the Ten Commandments (“You shall not steal. … You shall not covet your neighbor’s house; you shall not covet your neighbor’s wife, or male or female slave, or ox, or donkey, or anything that belongs to your neighbor”) as proof-texts proving that Harriet Tubman’s illegal theft was a form of sinful disobedience to God.

But that is not how earlier Christians would have viewed Tubman’s actions. For the first four centuries of Christianity, it wouldn’t have made sense to speak of “stealing from the rich to give to the poor.” According to the teaching of those Christians, the wealth of the rich belonged to the poor.

God created “all things for all,” Clement of Alexandria wrote. “Therefore all things are common; and let not the rich claim more than the rest.”

“The bread that you withhold belongs to the poor,” said Basil, “the cape that you hide in your chest belongs to the naked; the shoes rotting in your house belong to those who must go unshod.”

“When you possess the superfluous, you possess what is not yours,” Augustine wrote.

Granted, that same Augustine also wrote angry screeds against the Circumcellions like this: “The peasants are emboldened to rise against their landlords; runaway slaves, in defiance of apostolic discipline, are not only encouraged to desert their masters but even to threaten their masters, and not only to threaten them but to plunder them by violent raids.” At least part of that is a good description of Harriet Tubman’s life’s work. She certainly encouraged runaway slaves to desert their masters and, as a recruiter for John Brown’s raid, sought “to plunder them by violent raids.” But unlike the Circumcellions, she wasn’t going around beating people with clubs to try to provoke them into martyring them.

(Then again, we can’t be sure that the Circumcellions really did that either, since all we know about them is what we read from their opponents and critics. Their most enduring legacy, perhaps, is that they may be indirectly responsible for the rule in early versions of Dungeons & Dragons that forbade clerics from using edged weapons.)

In any case, I still think overall Augustine would not have viewed Tubman’s work as theft any more than he would have viewed Moses as a thief for stealing the “property” of the Egyptians.

And I’m sure that Harriet Tubman did not think of herself as a thief, even when the law and the Constitution did.