Everybody knows the story of David and Goliath from the Bible.

Well, actually, that’s not quite right. Everybody knows the story of David and Goliath. And the story of David and Goliath is from the Bible. But reading it from the Bible is not how everybody knows this story.

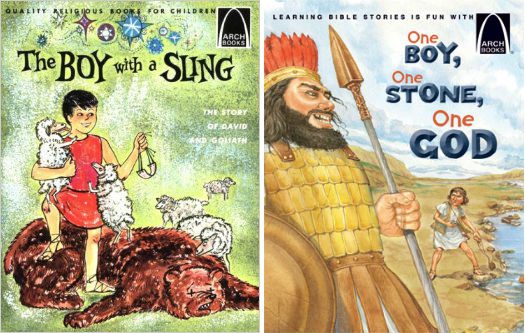

We know it from Sunday school, or from children’s story books, or from popular proverbs, paintings, or any of the many cinematic retellings and adaptations (Goliath of Gath has an impressive and surprisingly diverse page at IMDB, but it doesn’t include some versions of the story — like the one with the tank in the short-lived 2009 NBC show Kings.)

The Sunday school version of the story is never quite like the actual story in the text of the Bible. That actual text of the story doesn’t quite fit the purpose of such Sunday school lessons, in which stories from the Bible tend to be reduced to a simple, wholesome moral lesson for children. The story gets streamlined, simplified and embellished in the retelling in service of this moral lesson.

We first encounter the story in forms like that, absorbing it as a tale of the proverbial underdog triumphing over the odds with God’s help. That’s the story of David and Goliath that everybody knows.

Later, the few who ever get around to reading the actual story in the actual text of the Bible — in 1 Samuel 16-18 — tend to approach the text expecting to find this familiar story. The story we are expecting to find becomes the story we are looking for, and thus that is the story we imagine we encounter in the text. If we’re reading quickly or distractedly, the story we encounter in the text can almost seem to fit with that expectation. Almost. It’s close enough, anyway, to allow us to check off this chapter from our Through the Bible in a Year list, or to allow us to count our obligation of daily devotional quiet time as fulfilled.

But if we’re paying closer attention, we’ll notice that the text of 1 Samuel doesn’t quite fit. It doesn’t fit neatly with the story we learned in Sunday school. And it doesn’t fit neatly with itself.

If we read 1 Samuel 16-18 carefully and attentively, the text at first seems repetitive. It sets the scene and introduces the cast of characters twice. The repetition can lull us to sleep a bit, encouraging us to skim more than to pay close attention to the substance of what we’re reading. But if we let it jar us into re-reading the text more carefully, we notice that this text isn’t merely repetitive, but contradictory. It sets the scene and introduces the characters differently.

Even in our English translations, it’s pretty obvious that we’re not reading a single story in 1 Samuel, but rather, as Mits put it earlier in comments here, “two different origin stories … kind of glued together.”

Paul Davidson had a good overview discussion of this last summer in a post titled, “The Men Who Killed Goliath: Unraveling the Layers of Tradition behind a Timeless Tale of Heroism.” Davidson also helpfully separates out the two stories that 1 Samuel clumsily tries (and fails) to merge, reproducing them in parallel columns in an article bluntly titled, “The Two Stories of David and Goliath in 1 Samuel 16-18.”

This isn’t mere speculation from some pointy-headed ivory-tower liberal who’s trying to tear down the authority of the scripture as part of a liberal/secular conspiracy to destroy real, true Christianity. This is simply something we know to be true because people who love the Bible have studied the Bible.

And it is, in fact, something we know, in fact. Claims of absolute certainty are irresponsible, but we’re about as sure about this as it’s possible to be. As Davidson writes, after reviewing the inconsistencies between the two stories in the text:

Often, scholars use such inconsistencies to identify multiple sources or layers of redaction in the text. Usually, such analysis is conjectural and cannot be proven. However, in the case of 1 Samuel 16–18, we are fortunate to possess an earlier edition of the text — the Septuagint (LXX) of 1 Samuel, which must have been translated into Greek from an earlier version of the Hebrew book.

… Several parts of the story … amounting to 44 percent of the text, are completely absent from the LXX (and, by extension, the Bible still used today by Eastern Orthodox Christians). It is almost certain that the translator of 1 Samuel, who used an excessively literal and exacting approach when translating from Hebrew, did not have these portions in his copy of 1 Samuel. If these portions are removed and reassembled on their own, we end up with two complete, coherent versions of the story — the one found in the LXX (“story 1”), and one that was apparently interpolated into Hebrew 1 Samuel at a later date (“story 2”). Taken on their own, the two stories have few, if any, internal contradictions or inconsistencies. They have much in common, but they also differ in significant ways.

All of this raises two very large problems for those who are determined to squeeze the Bible into their modern construct of “inerrancy.”

The first and more obvious problem is that, as Davidson says, the two stories found in this part of 1 Samuel “differ in significant ways.” Their details clash and cannot be reconciled in the framework of “inerrancy.” If we want to claim that the account recorded in Story 1 is “inerrant,” then we are forced to concede that the account in Story 2 cannot be. Or vice versa. (This all gets further complicated if we also try to account for Story 3 — the story of Elhanan and Goliath found in 2 Samuel 21.)

The proponents of “biblical inerrancy” are thus forced to attempt to harmonize the two (three) stories. Such attempts are never pretty. Nor are they ever any more successful than the similar inerrantist attempts to harmonize, say, the accounts of Holy Week in the gospels, or the very different genealogies found in Matthew and Luke.

But the second problem for inerrantists here is larger and deeper and more essential — cutting to the heart of why “biblical inerrancy” is a fundamentally distorted and distorting approach to reading and understanding. The larger problem is not simply that the two stories in 1 Samuel contradict each other, but that the text’s attempt to merge them together is so transparent and seems, frankly, so poorly done.

The first problem, in other words, is that 1 Samuel 16-18 presents us with an example of an errant story — something the theory of inerrancy says ought not to exist. But the second problem is that this passage presents us with an apparent example of errant storytelling — something that suggests the theory of inerrancy itself should not exist.

What we’re up against here are the limits of the Procrustean framework of “biblical inerrancy.” The idea or framework of “inerrancy” simply crumbles when we attempt to apply it to many — or probably most — genres of literature. What would inerrant storytelling even mean? Is there any sensible way to speak of an “inerrant” poem? How do we solve the riddle of an “inerrant” riddle?

Wherever it encounters forms of literature that cannot be accommodated or accounted for by the categories of inerrant or errant, this framework is forced to treat those forms of literature as something else — as some other genre that can be assessed by that formula. The framework thus becomes a form of illiteracy — a way of reading that distorts meaning by failing to regard the text itself, turning it into something else instead.