Originally posted April 15, 2005.

Left Behind, pp. 77-80

Buck Williams was on his way to London when the mass disappearances occurred and his flight returned to Chicago. He had gone to Chicago to “mend fences” with one of his “Global Weekly” colleagues: “… [the]bureau chief there, a fiftyish black woman named Lucinda Washington.”

We meet Lucinda in a flashback because she is a Christian and therefore, in the present of the story, she’s dead/raptured. She’s the first Christian character we meet whose faith seems to have consisted of more than just sitting around, waiting to go to heaven. (She’s also the first black character we meet as Jenkins employs the Hollywood-shorthand device of demonstrating the virtue of a white character by showing that he has black friends.) Lucinda seems nice enough, although, like everyone else in the book, she talks funny.

Buck had annoyed Lucinda when he:

… scooped her staff on, of all things, a sports story that was right under their noses. An aging Bears legend had finally found enough partners to help him buy a professional football team, and Buck had somehow sniffed it out, tracked him down, gotten the story, and run with it.

“I admire you Cameron,” Lucinda Washington had said, characteristically refusing to use his nickname. “I always have, as irritating as you can be. But the very least you should have done was let me know.”

“And let you assign somebody who should have been on top of this anyway?”

“Sports isn’t even your gig, Cameron. After doing the Newsmaker of the Year and covering the defeat of Russia by Israel, or I should say by God himself, how can you even get interested in penny-ante stuff like this?”

That reference to the defeat of Russia “by God himself” is the real purpose of this little vignette with Lucinda, in which LaHaye and Jenkins offer a glimpse of the spiritual journey Buck has been on ever since he witnessed that event (see earlier, “The Babel Fish“).

You’ll recall that sometime before the events of LB begin, L&J explain that Russia launched a full-scale nuclear attack on Israel, unloading its entire nuclear arsenal on a country the size of New Jersey. Buck Williams was there, in Israel, at ground zero in a nuclear war. He witnessed firsthand the explosion of tens of thousands of nuclear warheads, each far more powerful than the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, without a single injury to himself or to any Israeli. It was an explicit, extravagant miracle — an act of divine intervention signed with a flourish by the hand of the Almighty. Having witnessed such a thing Buck — yet, strangely, only Buck — has come to believe in God.

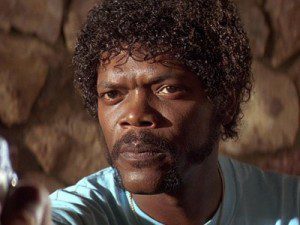

Buck’s spiritual awakening is a lot like that of Jules, Samuel L. Jackson’s character in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. Jules was a professional killer who experiences a revelatory “moment of clarity” after several shots fired at him point-blank failed to harm him. Jules regards this as a divine miracle and a sign that his life must change. Here’s how he describes it:

It could be God stopped the bullets, he changed Coke into Pepsi, he found my fuckin’ car keys. You don’t judge shit like this based on merit. Whether or not what we experienced was an according-to-Hoyle miracle is insignificant. What is significant is I felt God’s touch, God got involved.

We can envision a kind of chart or scale of the miraculous. On one end of the scale we can place serendipitous quotidian experiences that may or may not be providential — such as the answered prayers for parking spaces that seem to form such an essential element of American evangelical piety. On the other end would be, say, Moses’ personal interviews with God atop Mt. Sinai in which the hand of the Almighty reaches down to inscribe God’s laws in stone.

Jules’ example of the car keys would clearly be toward the lower end of this scale. The transformation of Coke into Pepsi would be slightly more impressive, but still not up there with the raising of Lazarus or the parting of the Red Sea. Jules’ partner, Vince, isn’t convinced that their not getting shot qualifies as a miracle, but only as a “freak occurence.” And Vince may be right — in the grand scheme of things it’s closer to car keys than to Sinai.

But what if, instead of a handgun, Vince and Jules had been fired on with a machine gun? Or what if they had been attacked by a military helicopter? The more lethal and devastating the weaponry involved, the more apparently miraculous their salvation would seem.

If the feckless drug dealer who attacked them had leapt out of the kitchen not with a handgun, but with a thermonuclear bomb, and if he had detonated that bomb, incinerating himself and everything for miles around — but not even slightly harming Jules and his partner, then I think even the skeptical Vince would have been persuaded to view this as an according-to-Hoyle miracle.

That, roughly, is what happened to Buck Williams. Multiplied by ten thousand. Buck’s experience in Israel was off the charts on our miracle scale. Moses and Elijah never saw anything like it. It was easily, clearly, far and away, the most spectacular, incontrovertible miracle of all time.

Yet no one in LB reacts to this stunning event with even a fraction of the awe that Jules displays in “Pulp Fiction.” Lucinda is portrayed as a devout, outspoken Christian. She believes the miracle was the work of God, but even she doesn’t convey the reverential wonder that Jules does:

“Come on, Cameron. You know you got your mind right when you saw what God did for Israel.”

“Granted, but don’t start calling me a Christian. Deist is as much as I’ll cop to.”

Buck means, I gather, “theist.” The uninvolved clockmaker God of Deism is not an intervening show-off. You cannot witness the hand of God swatting aside planes and the laws of nature like King Kong atop the Empire State Building and remain a Deist.

“Stay in town long enough to come to my church, and God’ll getcha.”

“He’s already got me, Lucinda. But Jesus is another thing. The Israelis hate Jesus, but look what God did for them.”

“The Lord works in –”

” — mysterious ways, yeah, I know.”

Buck believes in God, but he still got “left behind” because — like those Jesus-hating, Christ-killing Jews — he didn’t believe in Jesus.

Left Behind, in the chapters ahead, has a great deal to say about saving faith. LaHaye and Jenkins are clear that such faith only counts if it includes a very particular content, a very specific formula. For them, to be saved through Christ means to be saved by one’s acknowledgment of certain facts about Christ. At times, they seem to say that salvation is possible because of God’s mercy. At other times, salvation seems to be something we can compel the genie God to grant us by incanting the “sinner’s prayer.” There’s a magical, gnostic element lurking here we’ll get into a bit more down the line.