Originally posted June 10, 2005 — years before Mark Driscoll self-destructed by taking Rayford Steele’s attitude to the next level.

Left Behind, pp. 102-104

These pages find Rayford Steele on the edge of a spiritual crisis. Steele thinks of himself as a man’s man, self-reliant, capable and proud. Here, for the first time, he begins to experience self-doubt:

Would it mean admitting that he didn’t know everything? That he had relied on himself and that now he felt stupid and weak and worthless? He could admit that. After a lifetime of achieving, of excelling, of being better than most and the best in most circles, he had been as humbled as was possible in one stroke.

That last sentence is wonderfully ambivalent. If Rayford is really “as humbled as possible” then what’s with all the boasting about being “the best in most circles”?

On the one hand, Rayford has finally begun to question his own self-sufficiency. There’s a genuinely Christian element here. For a less evangelical take on Rayford’s dilemma, consider the analogous language of AA and the other 12-step programs. Rayford imagines he is at rock bottom and considers, for the first time, the possibility of “letting go and letting God.”

On the one hand, Rayford has finally begun to question his own self-sufficiency. There’s a genuinely Christian element here. For a less evangelical take on Rayford’s dilemma, consider the analogous language of AA and the other 12-step programs. Rayford imagines he is at rock bottom and considers, for the first time, the possibility of “letting go and letting God.”

But on the other hand, he doesn’t quite seem willing to let go. This might be an honest, even artful, depiction of the beginnings of a spiritual struggle except that the authors seem to share Rayford’s ambivalence.

He has lost one child, his young son, but not the other, his college-age daughter. We’ve already seen Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins’ explanation for this — Raymie was younger than the “age of reason” so he automatically receives the free ticket to heaven. Chloe is an adult who, like her father, was free to choose otherwise and thus, like her father, is “left behind.” Yet Rayford here looks for some further explanation for why his son was raptured/killed/saved and his daughter was not.

It wasn’t simply Raymie’s age and innocence that had allowed his mother’s influence to affect him so. It was his spirit. He didn’t have the killer instinct, the “me first” attitude Rayford thought he would need to succeed in the real world. He wasn’t effeminate, but Rayford had worried that he might be a mama’s boy — too compassionate, too sensitive, too caring. He was always looking out for someone else when Rayford thought he should be looking out for number one.

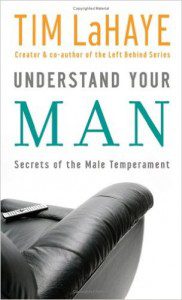

LaHaye and Jenkins acknowledge that self-reliance can be a kind of idolatry, or at least an obstacle to the surrender of self involved in surrender to God. They even approach the idea that some of our cultural notions of “manliness” contribute to this myth of self-reliance.

But at the same time, they like this notion of manly self-reliance — as demonstrated by that blurted out non-sequitur insistence that Raymie “wasn’t effeminate.” They want to be Buck and Steele — manly, capable men, “the best in most circles.” They can admit a need for God but not, you know, in some sissified way that would undermine their steely, young-buck macho self-reliance.

There’s a hint here of something I can’t quite fully suss out. An interconnectedness of L&J’s reflexive homophobia, their insistence on rigid gender roles and male dominance, and the strange notions of power and magic that color their notions of salvation. More on this later.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

In the previous installment, I quoted 1 John 4:18 as a summary and refutation of the notion of salvation portrayed in Left Behind:

“Perfect love drives out fear, because fear has to do with punishment. The one who fears is not made perfect in love.”

My point wasn’t that fear of judgment before a holy God is illegitimate, but that the God of the Bible desires and deserves much more than our fear. God wants our love. And I believe that God, unlike the abusive-husband-god of Left Behind, deserves it.

That post prompted a fascinating discussion in comments on the meaning of hell and judgment. I’ll revisit this topic in the future in more detail, but let me say here briefly that my own understanding of the meaning of hell follows that of C.S. Lewis in The Last Battle and, especially, The Great Divorce (kudos to Coriolis, Nicole and David for bringing those up). Lewis insists that all have the freedom to reject God, to “not be taken in” by heaven, but does so in a way that avoids the implication that God is the author of evil or, worse, a cosmic sadist. This perspective, I believe, best fits with the oft-ignored teaching — found explicitly in Hosea, the Song of Songs, and throughout the Bible — that God is a lover who woos us and longs for us to freely reciprocate that love.

We Christians attempt to believe that God’s love and mercy are infinite and that God’s justice and holiness are infinite. Holding both of those ideas at once is probably more than our finite little brains can handle, but I’m not prepared therefore to conclude that both can’t be true. I reject L&J’s insistence that God’s love and mercy are finite, but I don’t want, therefore, to conclude that God’s wrath and judgment are inconsequential. Anyway, we’ll have to dig into this in more detail later, but thanks to all for your very interesting comments on the previous post.