Earlier today I linked to Doug Muder’s Weekly Sift post in which he discusses the crackpottery of Republican presidential candidate Ben Carson.

That followed my own post about Carson, in which I quoted a bit from Maggie Koerth-Baker on “stuff that you long ago forgot isn’t general public knowledge.”

Put those together and it seems like a good time to revisit another old post of Maggie Koerth-Baker’s, on “Crackpots, geniuses, and how to tell the difference.” Here’s the core of that, where she suggests five rules for discerning whether the person you’re listening to is a genius or a crackpot:

1) If it makes a really nice story, ask for the details. (Good science usually makes a bigger deal out of the evidence than it makes out of the story. In fact, that’s actually a problem many legit scientists have—they’re better at talking about the details and data then they are at telling stories. But most of us respond to stories better than we respond to details and data.)

2) If the proof seems self-evident (i.e., it’s just good common sense), ask more questions.

3) If believing the idea will make you smarter than the official experts, be suspicious. Experts aren’t always right. But they do know their fields and experience does matter. Chances are, you’re an expert in something. Say you knew how to bake pies really well. You’d be pretty suspicious if somebody who didn’t bake (or didn’t even really cook much) told you that you were making pies all wrong — and that they had a secret pie recipe that was better than yours. They might be right. It’s worth taking a look at their evidence. But it also worth being skeptical.

4) If the studies used to prove it are really old, or if there’s only a few of them, dig deeper. What looks like truth when you look at five research papers can very quickly become completely untrue when you look at 500. What sounds like a good idea when presented by it’s originator can turn out to be terrible when you talk to a few other people. Try to get a sense of what the bulk of evidence is saying.

5) If you’re told you can’t trust any other sources of information (especially because of Big Conspiracy, or because so-and-so expert is a bad person in other areas of his or her life), be cautious. Replication is a powerful tool. It helps us get past accidental and intentional biases to see something closer to the truth. Suppressing replication is also powerful, because it leaves you with no way to check against bias.

All of this is good advice.

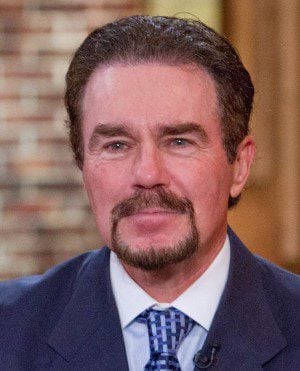

Nos. 3 and 5, in particular, seem particularly apt when applied to either Carson and his chief rival so far for the Republican nomination, Donald Trump.

In fact, those seem so utterly applicable to the Trump and Carson campaigns that I’m tempted to consider Koerth-Baker’s list as something that could easily be repurposed. She presents these five rules as warning signs that should cause you to be cautious that you may be dealing with a crackpot. But read them the other way around — as advice rather than warnings — and you’ve got what might be a sure-fire roadmap to the top of the polls this GOP primary season.