“Evangelicals really, really want to hear a story about sin and redemption,” Kevin Drum wrote. That’s true, but it’s not unique to evangelicals. Everybody loves a good story of redemption. As Kurt Vonnegut noted, “People love that story. They never get sick of it.”

The basic shape of this conversion narrative is essentially the same as what we sometimes call “Man in a Hole.” But, as Vonnegut notes, “It needn’t be about a man and it needn’t be about somebody getting into a hole.” The gist is, “Somebody gets into trouble, gets out of it again.”

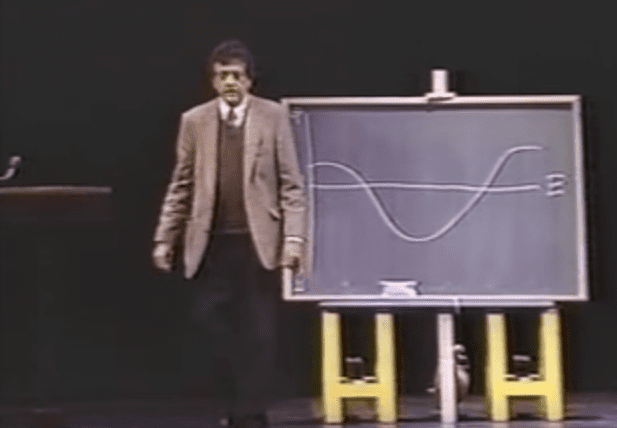

That quote is from one of my favorite things, a lecture/comedy routine in which Vonnegut helpfully graphed the shape of that story and of other stories on a chalkboard.

The vertical axis on Vonnegut’s graph is the “G-I axis,” with Good Fortune at the top and Ill Fortune at the bottom. The horizontal B-E axis starts at the Beginning and moves toward the End (although Vonnegut says the E stands for “electricity.”) As he reminds us, the shapes of stories are “An exercise in relativity. It’s the shape of the curve that matters and not their origins.”

And the shape of that curve encourages and rewards embellishment and exaggeration. Give that curve a more extreme downward slope and a steeper upward trajectory at the end and your story will have more of an impact. It will get a bigger response and audiences will want to hear it over and over.

Shakespeare knew this. He followed this formula in his three plays about Henry V, even going so far as to have the young Prince Hal spell it out, explicitly, for the audience (from 1 Henry IV, I, ii):

If all the year were playing holidays,

To sport would be as tedious as to work;

But when they seldom come, they wish’d for come,

And nothing pleaseth but rare accidents.

So, when this loose behavior I throw off

And pay the debt I never promised,

By how much better than my word I am,

By so much shall I falsify men’s hopes;

And like bright metal on a sullen ground,

My reformation, glittering o’er my fault,

Shall show more goodly and attract more eyes

Than that which hath no foil to set it off.

I’ll so offend, to make offence a skill;

Redeeming time when men think least I will.

People love that story. They never get sick of it.

That same formula applies to the “personal testimonies” we share in church. The ones we like best — that show more goodly and attract more eyes — are those with the starkest contrasts and the steepest curves.

If you have a relatively flat conversion narrative you’ll be politely thanked for sharing, but probably won’t be called on to share it again. The roller-coaster curves of the big-time sinners’ stories are more interesting and much more exciting. If you’ve got that kind of conversion narrative — with a much deeper hole and a much steeper climb out of it — then people will want to hear this story told and retold so often that you may be able to quit your day-job and become an itinerant evangelist with a ghost-written memoir published by Zondervan.

Daniel Burke discusses this in his CNN piece on “The dirty little secret about religious conversion stories.” Burke quotes from a Christianity Today* column by Ted Olson:

“Testimony envy may be part of any community,” Olsen wrote … “but we evangelicals seem to have a particular bent toward narrative one-upmanship.”

That’s all true. The white evangelical Christian culture rewards, and thus encourages, “testimony envy” and “narrative one-upmanship,” creating a not-so-subtle pressure to exaggerate the slope and the shape of our conversion narratives, making them more extreme and, thereby, less accurate and less true.

But it’s more than that.

And it’s more than just the temptation to give our stories, as Burke writes, “a little stretch” with an eye to make them more compelling calls for “winning souls for Christ.” That idea — that exaggerations are acceptable because they serve this higher purpose of spreading the gospel and saving souls — is a key to the rationalization that defends the tendency toward dishonest conversion stories, but I don’t think it’s the cause of that tendency.

Burke approaches that cause, almost parenthetically, but doesn’t explore it further:

Among the more notorious examples of salvation slipping into showmanship was Mike Warnke, a Christian comedian and evangelist who claimed to have converted after a violent and scandalous sojourn as a high priest in Satanism.

“Exaggeration did creep into some of my stories,” Warnke later admitted to an Oklahoma newspaper in 2000, “but my testimony is still my testimony.”

We’ve discussed Mike Warnke here before. Warnke’s testimony did not involve “exaggeration.” It was a bundle of lies — audacious, flamboyantly huge, deliberately crafted lies.

Vonnegut concludes the lecture in the video above by graphing the many curves and dips of the story of Cinderella — which he describes as the most popular story in western civilization. “We love to hear this story. Every time it’s retold, somebody makes another million dollars. You’re welcome to do it.” After the many dips and bumps in the shape of that story, Vonnegut ends by sweeping the chalk up and off the charts and drawing a little infinity symbol as Cinderella and the prince at last achieve “infinite happiness.”

Mike Warnke made his million dollars by inverting that curve. His lurid story of imaginary Satanism included a downward slope of off-the-charts, infinite depravity. That required an active imagination, but not as much originality as you might think, because ultimately what Warnke was doing was retelling another old story that has long been popular in western civilization — the story of blood libels and witch trials and inquisitions and black markets in baby parts.

Warnke did not need to break any new ground in order to describe infinite depravity and infinite evil. The description of that ultimate, superlative evil has been streamlined over the centuries into an efficient shorthand conveying all of that in a few broad strokes. Off-the-charts evil and depravity requires service to superlative, unsurpassable evil, so the first shorthand element to convey that is Satanism. And what do these Satanists do? Well, the worst thing we can imagine always gravitates toward murder, and the worst murder we can imagine involves killing the innocent, and the most innocent victims we can imagine are infants.

So that’s where this story always arrives. Always. Satanic baby-killers. A gifted storyteller will find ways to enliven that centuries-old trope by tossing in some depraved sex rituals, lots of gore, maybe some form of cannibalism. Warnke checked all of those boxes in his grisly, R-rated “testimony,” like a skilled comic riffing a particularly appalling variation of the old “The Aristocrats” joke.

And Warnke’s abominable testimony thus became a huge hit. It was, as Burke says, an act of “showmanship,” but the remarkable thing about that act wasn’t Warnke’s skill in presenting it — it was the audience’s eager hunger to hear his depraved tale told and retold. That vast audience was so enthused and delighted by Warnke’s version of the Satanic baby-killers story that I’m tempted to think Vonnegut was wrong about Cinderella, and that it’s only the second-most popular story in our civilization.

Tales of infinite depravity have a bigger fan-base than tales of infinite happiness, apparently — at least among white evangelical Christians.

That appeal and that popularity, I think, go back to the very thing that Shakespeare’s Prince Hal described — reformation glittering o’er fault. The stories we love best, that “show more goodly and attract more eyes,” are those that make the contrast between this reformation and fault most vivid. “Like bright metal on a sullen ground,” Hal says, but its far easier to make the ground seem more sullen — to “wish that black was a little blacker,” as C.S. Lewis put it — than to make the metal seem brighter. It’s easier to exaggerate our own brightness by exaggerating the surrounding sullenness into its most extreme form. And that leads us, inexorably, back to tales of Satan and of baby-killing.

When we contrast ourselves with those imagined Satanic baby-killers, even our blandest reformation doesn’t just seem to glitter, it dazzles. It’s a lie, an optical illusion, but it makes us seem to shine.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* Christianity Today is a publication that believes gay and lesbian couples are “destructive to society.”