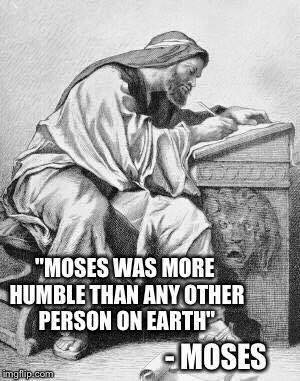

James McGrath shared the following meme, which he describes as an example of “one of many absurdities that result from viewing Moses as the author of the Pentateuch.”

The reference there is Numbers 12:3, which reads: “Now the man Moses was very humble, more so than anyone else on the face of the earth.” And, yes, it is a bit difficult to imagine that passage being written by “the man Moses” himself.

The reference there is Numbers 12:3, which reads: “Now the man Moses was very humble, more so than anyone else on the face of the earth.” And, yes, it is a bit difficult to imagine that passage being written by “the man Moses” himself.

Even more problematic, of course, is this bit from Deuteronomy 34, where “Moses” writes the history of his own death (just like poor Giovanni Villani):

Then Moses, the servant of the Lord, died there in the land of Moab, at the Lord’s command. He was buried in a valley in the land of Moab, opposite Beth-peor, but no one knows his burial place to this day. Moses was one hundred twenty years old when he died; his sight was unimpaired and his vigor had not abated. The Israelites wept for Moses in the plains of Moab thirty days; then the period of mourning for Moses was ended.

My fundamentalist teachers, when I was a kid, were deeply invested in the idea that Moses was the literal author of “the books of Moses.” Like everything else they believed about the Bible, they were keen on defending this point — sure that, like the historicity of Jonah and Noah, it was an essential link in the chain of biblical infallibility and inerrancy. That’s the thing about biblical infallibility and inerrancy — it’s only as strong as its weakest link. That’s why, for inerrantists, every jot and tittle is a hill worth dying on.

So they repeatedly defended Mosaic authorship by explaining that God dictated this account to Moses before his death, allowing him to finish the final chapters of Deuteronomy reporting on his own death and burial and much else that happened after that. (I did have one teacher who suggested that maybe someone else, maybe Joshua, wrote those final chapters of Deuteronomy. But this was viewed as a dangerously liberal line of thought — a slippery slope to some documentary hypothesis nightmare.)

For my part, even then, I didn’t understand this vehement defense of Mosaic authorship. I had taken too much to heart all the rest of what they had taught me about biblical literalism. Chapter-and-verse or it didn’t happen. And since this idea that Moses himself wrote these books wasn’t an idea that arose from the text itself, it seemed to young fundamentalist me to be an extrabiblical tradition and, therefore, something we were supposed to be skeptical about (just like sacraments and infant baptism).

Instead, I was struggling with some very non-fundie questions regarding a different part of the Hebrew scriptures — wrestling with a problem that parallels the one highlighted in that meme above. I was having a hard time reading the Psalms and reconciling them with the understanding of “plenary verbal inspiration” that we were being taught as an essential foundation of our faith.

Mind you, these teachers always took pains to insist that this didn’t mean the same thing as rote dictation. But they always struggled to explain how, exactly, it was different from that. God chose and determined every word, they said — every single, particular word — but this was different from dictation because it just was.

And then, after these discussions of the meaning of infallible, inerrant inspiration, we would turn to the other part of our Bible studies — memorization. And, quite often, that meant memorizing passages from the Psalms. Passages like this:

Bless the Lord, O my soul. O Lord my God, thou art very great; thou art clothed with honour and majesty. …

O Lord, how manifold are thy works! in wisdom hast thou made them all: the earth is full of thy riches. …

The glory of the Lord shall endure for ever: the Lord shall rejoice in his works.

He looketh on the earth, and it trembleth: he toucheth the hills, and they smoke.

I will sing unto the Lord as long as I live: I will sing praise to my God while I have my being.

My meditation of him shall be sweet: I will be glad in the Lord.

That’s from Psalm 104, one of the many great Psalms of praise that we memorized. It’s a beautiful, moving, heartfelt hymn of praise.

Or, rather, it would be a beautiful, moving, heartfelt hymn of praise if it hadn’t been the product of “plenary verbal inspiration.” But if we read that assuming that every word of it was chosen and determined by God — by the very same God who is the apparent subject of all that praise and adoration — then it just becomes something weird and kind of creepy.

If Psalm 104 was written by a human, then it is an inspiring text. But if it was word-for-word “inspired” — written down by a human at God’s behest as instruction to their fellow humans — then it seems not so much inspiring as intimidating.

The idea that these words were chosen by God — that God actively guided the writing of them — suggested something unsettling about the character of that God. It suggested that somehow God received all this predetermined praise just as though it were voluntary and uncoerced. Such an idea of God didn’t seem compatible with the substance of the Psalms of praise themselves. They described a God who was certainly entitled to the praise they offered, but who was also a God who desired voluntary love and adoration.

“Holy men of God spoke as they were moved by the Holy Spirit,” 2 Peter says of the biblical prophets. I don’t know precisely what that means as far as the mechanics of this “inspiration” go. But I do know this much: When it comes to the Psalms of praise and all the other praise-y bits of the Bible, that’s got to be our handiwork. Humans wrote that — otherwise it all means something different than what it says.