The prophets hated religion. More than that, the prophets insisted that God hated religion. This is a surprising thing to find in the Bible.

The prophets didn’t say this about some other religion — about the worship of idols or false gods. They said this about the very forms of worship, prayer, offerings, praise, hymn-singing, church-gathering, etc., that God had instructed and commanded God’s people to do.

This didn’t have anything to do with some kind of “proper attitude” during worship. It wasn’t about God’s people failing to conjure up the correct sentiment of earnest warmth in their stomachs. Nor did it have anything at all to do with sex stuff. Those are the two things we tend to project back onto the prophets in an attempt to explain away the blunt harshness of their condemnation of religion. Those are the meanings we try to force into their mouths when we try to tame these passages into some piously moralistic lesson about all our good works being filthy rags.

Yesbutofcourse, we say, our prayers and offerings and worship might be somewhat less than wonderful to God if we don’t have the proper attitude — the proper level of passionate sincerity and sincere passion. We pretend the prophets were worried about our feelings — about whether or not we really, really, really mean it when we do our religion things.

Or we assume that the prophets must have been talking about sexual stuff or idol worship, because we’ve somehow convinced ourselves that these are the major themes of the Bible — The Big Book of Rules About Sexual Stuff and Idol Worship. But, again, that’s mostly coming from us, not from the prophets themselves. In the passages where the prophets offer their strongest rejections of religion, they don’t mention any of that.

What they talk about, instead, is labor, wages, money, widows, orphans, strangers, and the poor.

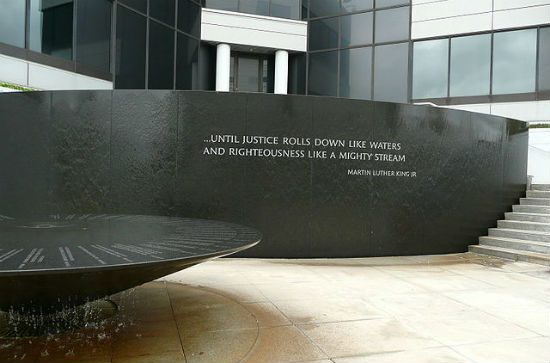

What they talk about is justice.

Justice is central and essential. Justice is everything for the prophets. It’s the thing that separates worship and prayer that pleases God from worship and prayer that God despises. Without justice, God hates our church-going, our hymn-singing, our praise choruses, our daily devotions, our tithes and offerings — hates them.

We have one more line of defense to prevent ourselves from accepting that. Because we need to defend ourselves from this. Our identity is bound up in our religion and our religion has treated justice as something marginal, optional, and mostly irrelevant. That makes what the prophets are saying an existential threat — something that threatens to upend our identity and to change what we see in the mirror.

So our next move is to try to scootch over a teeny bit to allow just a little more room for the idea of justice in addition to our otherwise unaltered religious identity. We keep saying all the things we said before: Prayer is Good. Church is Good. Worship and praise and offerings and daily devotions and evangelizing are Good. But we’ll allow that they’re not the only good things, and that perhaps — as inherently and intrinsically good as they all are — their goodness might not be quite enough without adding some additional good things of some vaguely justice-y nature.

It’s both/and, we say. We have to have both the intrinsically good religious stuff — worship, prayer, church-going, Bible study, etc. — and the justice-y stuff (the form and expression of which we’re far less specific about).

But again, this isn’t something the prophets ever imagined or mentioned. It’s not what they’re saying. They’re saying that prayer and offerings and worship without justice are not intrinsically good. Without justice, they say, all those things are despicable — loathsome and abhorrent to God. Abominable.

Yeah, “abominable” — the same word we like to pretend is exclusively reserved for idol worship and sex stuff.

“The language of Isaiah” is rude and harsh and brutally blunt. And so is the language of Amos and all the other prophets. It’s the sort of language that tends to provoke a lot of fretful hand-wringing from tone-policing busybodies who worry that such rhetoric is surely off-putting and somehow worse than whatever injustices it may be directed against.

Here, again, is the sort of thing they had to say about worship and prayer, offerings and pious church-going, hymn-singing and all the rest. And they all said this wasn’t their language, but the language of God Almighty:

I have had enough … I do not delight … an abomination to me [God] … futile … I cannot endure … my soul hates … a burden to me … I am weary of bearing them … I will not listen … dross … wormwood … evil … I hate, I despise …

That’s just a sampling from two piquant passages — Isaiah 1 and Amos 5. There’s much, much more where those came from.

That language of disgust is all directed at religion and the stuff of religion — the very same prayers and worship, church-going, offerings and praise-singing and devotional reading that we’re commanded to do and commended for doing elsewhere in the Bible. If we’re paying our workers a living wage and caring for widows, orphans, strangers and the poor, then all this stuff seems to make God happy. But these things are not intrinsically good. If we do any of those things while we’re exploiting our workers and allowing widows, orphans, strangers and the poor to be abused, then God has had enough. God does not delight in them but considers them unendurable abominations that God’s soul hates and despises.

Prayer and worship without justice doesn’t get you half credit. It seems, rather, to incur more of God’s wrath than if you hadn’t bothered to pray and worship at all.