“Racism is sin,” the court evangelical Rev. Robert Jeffress said last week. “Period.”

This statement is right and true and accurate. It seems helpful and constructive. It seems straightforward and unambiguous. That’s all good.

But, alas, once we inspect this statement a bit we find that it’s not quite so clear. There are layers of ambiguity here which can make such an apparently forceful statement confused and confusing. Rather than providing moral clarity, this ambiguity can wind up leading us morally astray.

We discussed one aspect of this last week, examining the way that Jeffress seemed to use this statement to redefine “racism,” limiting it to only that from which he could declare himself to be innocent. In the wake of Charlottesville, Jeffress was saying that violent Neo-Nazis threatening synagogues and running down pedestrians in the street were an example of racism. That’s true! But he also seemed to be suggesting that “racism” was confined to such overt, explicit acts of deadly hate. And therefore that anything else — anything less overt and explicit and deadly — was something other than “racism.”

And thus, therefore, that he personally must be found innocent of the charge of racism because, after all, he was not marching with torches, chanting Nazi slogans, or burning crosses. This seems to be the primary function of many of the public condemnations of “racism” we have seen performed over the past 10 days. It’s a familiar script. “Racism is sin,” the script says, but the purpose seems less to condemn the sin than to demonstrate the innocence of the person reciting that script.

The apparent clarity of this blunt statement — “racism is sin” — gets muddied by a confused understanding of the first half of that equation. And it gets further muddied by a confused understanding of the other half as well — by a muddled and misleading notion of the meaning of “sin.”

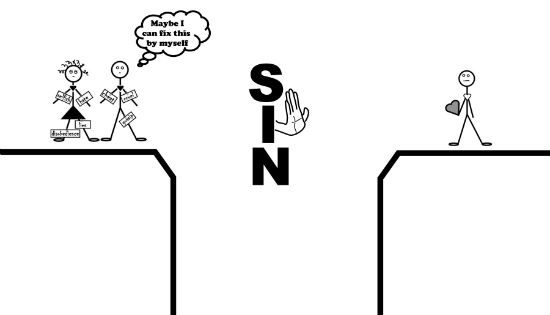

When white evangelicals discuss sin, it’s often in the context of sin and salvation — of evangelism. Popular approaches to evangelism as practiced by evangelicals take a prosecutorial, adversarial approach to sin. The first piece of this “gospel” message is usually “You’re a sinner.” The “Bridge illustration” starts by asserting the existence of an insurmountable chasm of sin separating us from God. The “Romans Road” presentation of “the gospel” starts with “all have sinned” and then segues into “the wages of sin is death.” Even the “Wordless Book,” designed to present the plan of salvation for children, begins with the prosecution’s case as illustrated by the sin and guilt of the “dark” page.

(This is perhaps an odd way to begin “sharing the gospel.” The first step for the evangelist becomes convincing the would-be convert of their sin and guilt. The evangelist thus acts as the accuser. There’s a formal, biblical name for “the accuser” or “the adversary.” That name is not usually associated with evangelism.)

We should note, though, that this prosecutorial discussion of sin is always universal. “All have sinned and fall short.” “There is none just, no not one.” When the evangelist accuses the would-be convert of sin, they’re not suggesting this that this makes that person exceptional. “You’re a sinner. I’m a sinner too. We’re all sinners.”

This sincere, emphatic insistence on the universality of sinfulness is interesting in light of the claim we’re discussing here. Say, “You’re a sinner, too” to even the most piously devout evangelical and they will wholeheartedly agree. They will almost happily agree — without any trace of offense or indignation. They may even up the ante — enthusiastically insisting that their sin means they’re no better than anyone else, because breaking one commandment is the same as breaking all of them, or because entertaining sinful thoughts is just as bad as committing sinful acts.

“You’re a sinner too!” “Yes, yes, I am. We all are.” And this cheerfully unoffended agreement can even endure if the shared accusation is made more specific.

“You’re a liar, too!” “Yes, we have all missed the mark of perfect honesty.”

“And you’re an adulterer, too!” “Yes, yes, we’ve all entertained lust in our hearts.”

But this comes crashing to a halt when we arrive at “racism is sin.” Somehow it’s perfectly fine and wholly agreeable to insist that we’re all sinners, but we get angrily indignant and defensive if anyone suggests that we’re all racists. This particular sin seems to be regarded differently than most other sins. It seems to be the one sin we are incapable of confessing, the one sin we refuse to allow ourselves to be accused of.

That’s … interesting. Evangelist-prosecutors wouldn’t allow anyone to speak this way of any other sin. They would never accept such an indignant claim of total innocence from any would-be convert who asserted that they had never lied or stolen or envied or lusted. But this sin, somehow, is different.

It’s astonishing, if you think about it. People who are perfectly willing to admit that they are wretched sinful sinners deserving to suffer an eternity of conscious torment in Hell due to their wicked sinfulness will turn on a dime and proclaim their absolute innocence when it comes to one particular sin.

Perhaps this is because they know themselves to be wholly innocent of this particular charge.

Perhaps it is because they know themselves to be utterly guilty of it.

Part of the problem here, I think, has to do with the more general misunderstanding of what “sin” means that I mentioned above. Getting into that will require a bit more discussion, so let’s reserve that for a second post.