The Tao Te Chingis a book about leadership and governance. Many of its chapters are addressed to an ideal emperor or king. Since most of us are not in line to be emperors or kings, we may wonder how such instructions are relevant to us. To understand this, it helps to recognize an idea that is quite common in ancient spiritual philosophy: the microcosm reflects the macrocosm. In terms of leadership, this idea suggests that there is a clear link between how an individual governs his or her own life; how a matriarch or patriarch governs a family; how a local official governs the community; how the king governs the state; and how God or the Tao governs the cosmos. Since we are each emperor of our own being, instructions to the emperor can be translated into terms of how the spirit is to govern the body and soul. (1)

The Tao Te Chingis a book about leadership and governance. Many of its chapters are addressed to an ideal emperor or king. Since most of us are not in line to be emperors or kings, we may wonder how such instructions are relevant to us. To understand this, it helps to recognize an idea that is quite common in ancient spiritual philosophy: the microcosm reflects the macrocosm. In terms of leadership, this idea suggests that there is a clear link between how an individual governs his or her own life; how a matriarch or patriarch governs a family; how a local official governs the community; how the king governs the state; and how God or the Tao governs the cosmos. Since we are each emperor of our own being, instructions to the emperor can be translated into terms of how the spirit is to govern the body and soul. (1)

The Taoist had noticed how Nature governs (or self-organizes) without effort. The sun moves effortlessly through the heavens, spring effortlessly follows winter, the tree effortlessly puts forth blossoms and fruit, the baby effortlessly forms within the mother’s womb, and the infant effortlessly grows to adulthood. This effortless effort, wu-wei, became the Taoists paradigm for how to govern.

The notion of a chain of being between the governance of the cosmos and the individual’s self-governance is also found in the West. Here, however, a human-like ruler is often projected into the image of how the cosmos is governed. The mythologies of the West often portray a God who must rule a rebellious nature and force it to conform to his bidding. (In the Judeo-Christian mythologies, first the angels rebelled against God and then Adam and Eve disobeyed him.) Following the lead of God’s governance, the chain of being gives us kings who must police and punish rebellious subjects, parents who must mold recalcitrant children, and individuals that must tame and restrain their rebellious souls.

In the Judeo-Christian myths, the world has at its base fundamental oppositions, most notably the opposition of good and evil. The ruler has to put things into their place and some things have to be rejected altogether. Following the cosmic model, the Western individual is taught that there is a whole range of activities deemed wrong or sinful that should to be excluded from the soul. In the history of Western Christianity, sexuality, one of the soul’s strongest inclinations, was deemed to be particularly wrong or sinful, and this emphasis on rebellious sexuality forced the spirit to have an increasingly oppositional relationship to the soul, as does a tyrant to a rebellious kingdom.

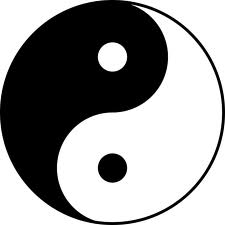

In Taoism, the Tao represents the fundamental of the world. Within it, such oppositions as good and bad, subject and object disappear. As the Universe comes into being, its self-organization engenders oppositions and the dynamic tension created by these oppositions furthers the self-organization of the world. Mythically, this opposition is given the names of yin and yang, the feminine and masculine principles. In naturalistic terms yin and yang can be thought of as such oppositions as the positive and negative charge of the electromagnetic force; of gravity with the electromagnetic force (think of rain, where the electromagnetic force of the solar energy evaporates water and raises to the clouds until gravity calls it back to earth as rain); of sun and earth; matter and form; male and female.

The Taoist individual, like the Taoist cosmos, recognizes that there is a place for everything in the soul and seeks to find that place. Nothing need be excluded. The spirit (what might be called the yang aspect of the Taoist being) seeks to cultivate the soul, as the gardener cultivates the garden – a metaphor worth exploring further.

In the classical Western garden, there were clearly favored and unfavored plants. The unfavored plants – weeds — were simply irradicated. Gardens were highly ordered, often on some geometric principle, and the gardener’s job was to maintain the order.

The garden of the Orient was organized, but the organization was complex, flexible and accommodative, and the less noticeable the organizing principles, the better. While such a garden may have highlighted some special plants, it often made room for native plants in places that were allowed to grow wild. The organization also took advantage of the natural lay of the land, particularly any rises or watercourses. The garden did not seek to transform Nature to some ideal, but to improve on what Nature already provided – to make it more amenable for humans.

The human soul has its animal wildness. St. George fighting the dragon is an apt symbol of the soul perceived as a dangerous wildness that must not only be subdued but extinguished. Dragons are usually celebrated creatures in China, and that is perhaps because the culture understands that the animal wildness of the soul is also its possibility for creativity and delight. This animal wildness does need to be curbed somewhat, it needs to be cultivated, but if done correctly the energy of the soul is not extinguished but channeled and enhanced

At the core of Taoist psychology is the notion of Taoist contentment. This is not the ephemeral contentment of a person who has had a good meal or the smug contentment of a person who has one-upped his neighbor — it is a dependable and enduring contentment that comes from the cultivated animal energies of the soul. It is the great dragon resting contentedly, like a purring cat, in the depths of one’s being.

The Western soul with its exclusionary principles makes of the soul a place of conflict, an often harsh or empty place. The Western spirit turns outward, and in the end becomes a consumer of the outward world, as it tries to fill the emptiness of the excluded soul. (2) This Western turning outward obviously has had its benefits. It has led to tremendous skills in knowing and shaping the outer world. While the shadow side of these benefits has led to increasingly uncertain environmental and economic conditions, none-the-less these benefits certainly are not to be scorned.

The Taoist spirit cultivates the soul, seeking a place for all of its diverse energies. A well cultivated soul is a delightful place. Thus the Taoist can turn inward for delight and comfort. It is in this spirit that the Tao Te Ching states that “though he hears the cock’s crow in the next village, he feels no need to visit it.” The world of external goods has its value, but to be utterly at home in your own soul – is that not a greater value? And that is where the Way ever leads.

Subscribe to The Spiritual Naturalist Society

Learn about Membership in the Spiritual Naturalist Society

__________

The Spiritual Naturalist Society works to spread awareness of spiritual naturalism as a way of life, develop its thought and practice, and help bring together like-minded practitioners in fellowship.

__________

Written by Thomas Schenk.

__________

Note (1): Here the word “spirit” refers to that part of our being which is able to articulate, judge, set goals and strategies, and maintain focus until goals are achieved. “Soul” refers to the total inner being, including the unconscious, appetites and desires, emotions, fantasies and intuitions, and in the final end, that which has above been labeled “spirit.”

Note (2): Like much in this article, this is an over simplification.