Over at Aleteia, Father Dwight Longenecker has a piece about Pope Francis as “reformer”:

Francis is hailed as a “reforming Pope” and he certainly seems intent on carrying through the plans initiated by Pope Benedict. Is it best, however, to regard him as a “reforming Pope”?

People can and will make their own determination about that, but Dwight’s not wrong that — public perceptions and media narratives aside — Francis is certainly moving forward on some Benedictine initiatives, even as he puts his own stamp on the future of the Church. As the excellent John L. Allen, Jr helpfully points out, yes, there are differences between the men but also more similarities, perhaps, than some might acknowledge. Allen is a generous sort, and always quick to give Benedict his due. [Scroll down at that last piece – admin]

Recently, I was talking about Benedict and Francis with a friend who is still “reserving judgement” on Francis, and missing Benedict a little. After Francis’ most recent controversial airplane presser she wrote to me, extolling Francis for his candor and clear love for the people, but wondered, “is it possible that he is not much of an intellect? Or not reflective in a rigorously logical way?”

She went on to mention favorite saints of hers who were not intellectual giants, and might have been problematic popes (dear Solanus Casey comes to mind) and wondered if that was part of what unsettles some about Francis: on the surface, he appears to lack Benedict’s clarity or John Paul’s depth.

She may have a point. Most modern priests may have advanced degrees, but they are not, on a primitively-Catholic level, absolute requirements for the papacy — Peter didn’t have one!

Still, I’ve often wondered if part of the problem with Francis is simply that he is neither as well-read nor as scholarly as our two previous popes. Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI both possessed multiple PhD’s and were deep thinkers — a philosopher and a theologian, respectively; they were both trained in argument, trained to European disciplines of discourse and study; both talented linguists.

Francis has a Master’s Degree in Chemistry, and he is no linguist; immediately the difference is apparent. Ironically (sometimes distressingly) he is perhaps the most talkative of our popes. He brings a South American sensibility to him — less disciplined, more colloquial, a little bit (dare I say it) insensitive to Western norms in his references to women, for instance.

We get the pope we need. Saint John Paul was the re-awakening dramatist, Papa Benedict the necessary teacher, this pope, Francis, is the missionary — and we need a missionary pope, because, whether we realize it or not, the 21st century will call us to be once more the missional church we had more-or-less ceased to be. And we’re going to be missioning in a concrete jungle, full of people who have heard the name of Jesus a million times, but have yet to meet him, and must do so in us.

A Patheos writer recently said to me, “these Francis-haters would be having strokes if JPII were pope today, as he was in his heyday, kissing Korans, and so forth…”

When he said that, I realized that John Paul would not have been free to be John Paul — and all he became to the world during his papacy — without the anchor of Benedict. He was the “pilgrim” pope, traveling more than any before or since, becoming the first “rock star pope” and writing dense, often impenetrable philosophical treatises, while Benedict quietly supported him, wrote and taught, dealt with curia politics and doctrinal matters and carried a great deal of responsibility on his shoulders, particularly as John Paul reached his culmination.

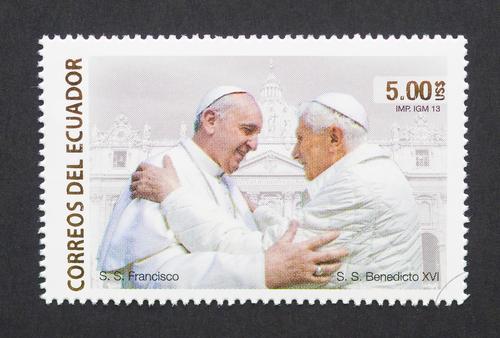

And now, Benedict is very much an anchor for Francis — who would not even be sitting as Peter, had Benedict not read the times and realized that no one was listening anymore; that something almost unprecedented was needed to change the narrative and shake the assumptions of the world. I am still unpacking the lessons of trust and discernment that Benedict modeled for us when he threw the entire church — and by extension the whole world — into the path of the Holy Spirit.

Francis, by his own words and actions, has captivated the imagination of the world, and if he seems flightly or undisciplined to some, it is a limited flightiness. The anchor of Benedict has literally grounded Francis to realities that must be confronted. As John Allen writes:

[It is] clear that Francis tends to get credit for several perceived reforms that actually began on Benedict’s watch, especially in two chronic sources of scandal for the church: money and sex abuse.

On money, it was Benedict who created a new financial watchdog agency, who opened the Vatican for the first time to outside secular inspection through the Moneyval process (the Council of Europe’s anti-money-laundering agency), and who appointed a new president of the Vatican bank who just released its first independently certified financial statement.

On sex abuse, it was then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger who pushed for new rules to weed out abuser priests in the Pope John Paul II years and who wrote those rules into law as pope. It was also Benedict who unleashed his top cop, then-Msgr. Charles Scicluna, on Mexican Fr. Marcial Maciel Degollado despite the cleric’s powerful network of Vatican allies and sentenced Maciel to a life of “prayer and penance” in 2006. Benedict, too, was the first pope to meet with victims of sex abuse, the first pope to apologize for the crisis in his own name, and the first pope to dedicate an entire document to the abuse crisis in his 2010 letter to the Catholics of Ireland.

[It was Benedict who] laicized almost 400 priests over his last two years in office for reasons related to sex abuse, which isn’t quite the profile of a pope in denial. If you think about it, that’s almost 1 in every 1,000 Catholic priests in the world flushed out of the system by Benedict in just two years.

No doubt Benedict’s record on these matters is open to criticism, but there’s equally no doubt that he got the ball rolling on reform. In other words, if there’s a case for “Benedict bad, Francis good,” it’s not on these two fronts.

All three men possessed their own gifts and faults, their strengths and their weaknesses, as their humanness warrants. But it seems to me that Joseph Ratzinger/Pope Benedict was unique in that he managed to bring to the church whatever needed shoring-up within the pope preceding him and the one following. He is, very quietly, the well-anchored, stable, and largely-unappreciated, pole around which two dynamic and larger-than-life papacies could spin.

When a centering pole is solid and well-anchored, it tends not to be thought about, because it is simply doing what it is supposed to do, as Benedict would likely be the first to say.

Related:

Benedict has No regrets

The Papacy is an office of tenderness, served under a heavy cross.