Paul had a problem with the Torah.[1] There is no denying this fact.

The nature of the problem, however, is certainly up for debate.

Growing up as a child of evangelicalism, the problem was often framed in binaries: law vs. grace or religion vs. grace or works vs. faith or flesh vs. Spirit or slavery vs. freedom. All of these dualities get at the same thing: the old Hebrew covenant was needed, but only so that at the fullness of time God could establish a new covenant that trumped the archaic (but temporarily needed) legalism of the Torah.

Pastors that I greatly admire picked up on this tradition of reading Paul (often applying it to the Jesus of the Gospels). From this viewpoint, the Apostle to the Gentiles (Paul) was a spiritually motivated iconoclast within Judaism who favored a life of obedient freedom in Christ and “law of love” over the religious checklists of the Pharisees and Sadducees. The foundational question in many churches is: What do I have to do to know I’m ‘right with God?’ The answer: Nothing! Grace is opposed to works. God loves people just as they are. Works/deeds are the outflow of a life rooted in grace, but not the requirement for receiving it.

Although I now disagree with this reading of Paul, I don’t fault well-meaning pastors who preach his letters in this way. In fact, it may be what some people need to get out of a cycle of damaging spiritual self-talk that measures one’s worth by how “good” a person is instead from a posture of inherent human worth. To believe that the Divine is on your side—before doing anything at all—this is truly good news. Much of this preaching from the boomer generation comes as a response to the mantra of many of their parents and grandparents (that now has mostly become a joke, even to aged folks): “Don’t smoke, drink or chew or go with girls who do.” Many boomers and gen X-ers were appropriately responding to legalism within evangelical Christian culture with the categories available for them: law vs. grace.

The Problem with Evangelicalism’s Problem with Torah

Reading Paul as resisting legalism has come under serious scrutiny in the scholarship of the late twentieth century up until now. For what would become broadly known as the “New Perspective on Paul,”[2] the Apostle wasn’t responding to legalism. In fact, the practices of Judaean persons weren’t aimed at making sure someone was “right with God” at all—at least not in the salvific sense that is assumed by most Christians. Rather, Judaean practice was about responding to the grace of God who had allowed the Judaean people to be elected into the covenant, with a symbolic entrance point being circumcision. In other words, Judaeans weren’t attempting to “stay saved” or “earn salvation” by living perfectly under the law. They were “in” from birth. Their response to God’s grace—what we might call “covenantal faithfulness”—was to live in accordance to Torah. Torah helped them maintain right-standing with God in light of grace, not to earn and re-earn it through ritualistic practices. Thus, Paul can say things like “no one is justified before God by the law” (Gal. 3.11, NRSV) because even Judaeans aren’t/weren’t justified (made right) by following the law (Torah). They were justified by God’s covenantal faithfulness, the grace of God to them, which was lived out through Torah.

For New Perspective scholars, then, the problem that Paul had with Torah isn’t legalism in any sense, but rather that it (from this view) serves a boundary-marking function of exclusion.[3] The law’s practices (including the entry point of circumcision for males) are the very things that separate Jew from Gentile. Now that Christ has died for all and removed these distinctions (see Galatians 3.28), the law isn’t needed (insofar that it promotes ethnocentrism) as it has been redefined around the Messiah, community, and the Spirit.

So what we then deduce from this approach is that Torah observance for ‘messianic’ Jews like Paul became increasingly negative in their rhetoric about the law while also acknowledging that it had a good purpose. Different scholars approach these benefits/negatives of the law in various ways, which are too numerous to explore in this brief essay. Suffice it to say that the New Perspective started an important conversation about the nature of Judaean religious practices shifting the problem Paul had with Torah from legalism to ethnocentrism. But perhaps they didn’t go far enough to really deal with the dualisms of law vs. grace.

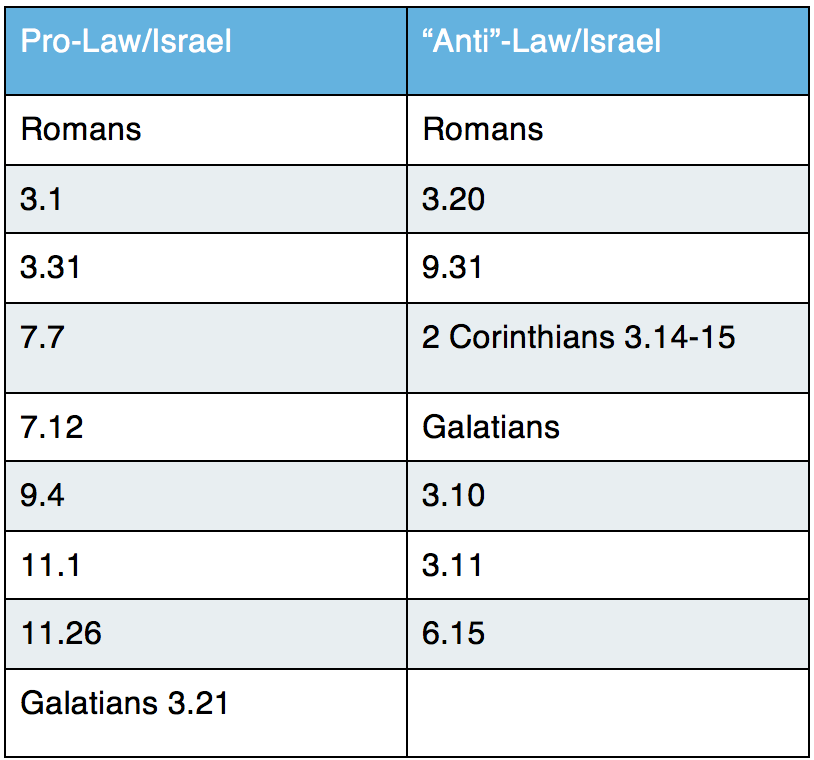

Is Paul’s real concern with boundary-keeping and ethnocentrism? Certainly Paul would be upset if these sorts of things were found within his communities. Even today, we can imagine shifting the old law vs. grace preaching to boundary-making and determining (perhaps even legalistically) who’s in and who’s out. Paul would likely not want to play such “religious” games. However, his view of the law is so positive at times that we have to wonder if there is a better way to think about his approach to the Torah. Consider the chart with various examples of how Paul seems to speak out of both sides of his mouth. No wonder Paul’s understanding of the Torah is so difficult to grasp!

Paul’s Problem with Torah is for those Outside of Torah

In order to believe that Paul becomes increasingly anti-Torah, at least in the sense that its season of relevance has passed because of Jesus’ new covenant inaugurated through resurrection, one must assume that everything Paul says about the law is directed (unless clearly specified) at a mixed audience of Judaeans and gentiles (really, gentiles should be translated as “the nations” but we will go with the conventional use for now). Circumcision is bad for everyone, in other words, as an obvious example. Or to make it even more relevant to real life: If Paul were married and had a male son, would he have circumcised his child in light of the gospel of Jesus?

Until recently I would have answered that question with an adamant “no.” Paul certainly believed that these boundary-making practices were put to death in the tomb with Jesus. However, I’m now quite comfortable believing that Paul would have had his theoretical son circumcised. I can’t see any better way to read Paul’s dialectic around the Torah than to come to the conclusion that he believed that Judaeans ought to remain in covenant relationship with God through the means they always have and that the negative rhetoric about the law are aimed exclusively at gentiles. As John Gager wrote:

Any statement that begins with the words, ‘How could a Jew like Paul say X, Y, Z about the law,’ must be regarded as misguided. In all likelihood Paul, the apostle to the Gentiles, is not speaking about the law as it relates to Israel but only about the law and Gentile members of the Jesus-movement.[4]

What I’m claiming, then, is that Paul does in fact have a real problem with Torah—for the gentiles only. The peoples from the nations do not have to become Judaeans in the formal sense, through circumcision and being absorbed into the Judaean ethnos (identity). They only need to trust in the faithfulness of Christ that he acted on behalf of the gentiles to bring them in just as they are: as gentiles (see 1 Corinthians 7.17-20 for an example of this logic).

In this way, they are to be gathered as distinct peoples to the worship of Israel’s God—an expectation that Paul clearly has inherited from the prophets (see Isaiah 2.2; 45) and his understanding of the covenant with Abraham that his decedents were blessed to become a blessing to every family on earth (Genesis 12.1-3; Galatians 3.1-9). Paul’s gospel was that active Torah observant Judaeans were seeing the launch of the end of days as the nations/gentiles gathered to worship Israel’s God, and thus, through Jesus’ faithfulness a Judaean plus Gentile covenantal community was now possible. Paul wants Jews, even messianic Jews, to remain faithful to Torah. He wants gentiles to remain gentiles, while at the same time refusing to worship pagan gods of the empire (Galatians 4.8-11).[5]

Issues that Need Further Examination

This approach to Paul’s “problem” with the Torah raises many important questions. Briefly, I will make some initial comments about these questions, recognizing that more space will be needed to truly flesh them out.

Does Paul, then, have a two covenant model? Yes, sort of. This comes through in Romans 8-11, specifically through Paul’s need to address the arrogance of non-Judaean Jesus followers who seem to think they have the advantage now in God’s plan. Paul’s response to them is that in the end “all Israel will be saved” even if for now, they have been hardened to the Jesus message. There is one covenant it seems with two tracks. These tracks will eventually meet at the end of the age when Christ is revealed as the world’s true Lord, of both Jews and gentiles.

Then, is Jesus the Messiah for Israel or is he only significant for the gentiles? This is a question that requires pages of examination. For now, I do think that Jesus is important beyond simply being the means through which the nations are grafted into the covenant. Why else would Peter, for instance, be called the apostle to the Jews? I suspect that there is more significance than merely announcing the end of the age has arrived. For instance, Paul’s emphasis on life in the Spirit of God/Christ (i.e. Romans 8, Galatians 5) seems to be something that only those who have trusted in Christ’s faithfulness get to experience.

So the Spiritual Temple language in Paul is only for the gentiles and Jesus-believing Jews? Yes, that is my opinion. This image comes up in 1 Corinthians 3 and 6, for instance, and seems to be directed at a gentile audience who do not participate in the physical temple worship in Jerusalem. They, through the mystical presence of Christ’s spirit are a spiritual temple (which would include Jesus-believing Jews). God’s experiential presence seems to have moved beyond the walls of the temple into the life of the community. However, nothing indicates that God’s experiential presence has left the building (temple) either. These are two different ways to encounter Israel’s God, but trusting in Jesus seems to have as an advantage the presence of the Spirit. Jesus believing Judaean worshipers presumably have the best of both worlds.

The Ongoing Problem of Torah Doesn’t have to be a Problem

Clearly, the way we speak of Paul and the law has ramifications for how faith communities live. Although pastors may have good motives to remove shame and guilt induced by legalism, the unintended ramification may be a distorted view of Judaism. Our rhetoric has built walls between Christians and Jews that a more nuanced approach might dismantle. The stones from that wall of hostility would be better repurposed as the building blocks of a bridge. This reconsideration of evangelicalism’s approach to Paul may lead to some beautiful new possibilities.

And the old problem of legalism and boundary-keeping, if these aren’t problems Paul is addressing then perhaps they aren’t our problems after all. Perhaps the solution for evangelical preachers might be found in reclaiming a unique trust in a God of love who through the faithfulness of Jesus has an open door policy to everyone: failures and all.

—————————————-

[1] From here on out, unless otherwise noted, I will use “Torah” and “law” as synonyms.

[2] Typically, this scholastic movement is considered to have its origin in the work of E.P. Sanders. Those who followed his lead often site that they agree with him on the basic nature of Judaism in the second temple period, but that he struggled to build a stable bridge to apply these insights to Paul’s gospel.

[3] This is especially evident, with different nuances, in N.T. Wright and James Dunn.

[4]. John G. Gager, Reinventing Paul (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000),44.

[5] Here, it is important to note that the calendar in question in Galatians 4 is the imperial calendar, not the Judaean one. See Mark D. Nanos, “A Jewish View,” in Four Views on the Apostle Paul, ed. Michael F. Bird (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2012), 184-186, n. 20.

======================================================

THIS WEEK ON THE SERMON PODCAST: In this first message of Subverting the Christmas Empire, Kurt dives head first into the Gospel/Good News of Caesar Augustus. This is the dominating story that Jesus is born into and yet somehow upstages. The story that places power and the gods in the center is subverted by a story that seeks its influence from the margins of Bethlehem. We American Christians have a lot to learn about Kingdom influence, especially during the holiday season: iTunes, Feed.

THIS WEEK ON THE SERMON PODCAST: In this first message of Subverting the Christmas Empire, Kurt dives head first into the Gospel/Good News of Caesar Augustus. This is the dominating story that Jesus is born into and yet somehow upstages. The story that places power and the gods in the center is subverted by a story that seeks its influence from the margins of Bethlehem. We American Christians have a lot to learn about Kingdom influence, especially during the holiday season: iTunes, Feed.