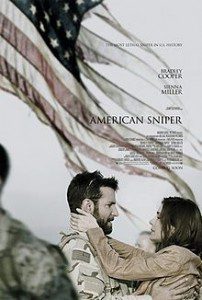

The movie American Sniper is not only January’s most successful movie ever (over $105 million during MLK weekend). It’s a cultural battleground.

The movie American Sniper is not only January’s most successful movie ever (over $105 million during MLK weekend). It’s a cultural battleground.

Some have decried it, saying that it depicts killing in righteous terms, which is categorically wrong. This is no small matter; The New Republic opposed it, and the critic hadn’t even seen the movie. For others, such as combat veteran David French (writing for National Review), the movie deserves acclaim for its celebration of heroism. Clearly, this is a film that has struck a chord.

Here’s what stood out to me about American Sniper: it gives America back its traditional vocabulary for manhood. Manhood has historically been an enterprise in ambition on behalf of others. Men have been trained for centuries to lead, protect, and provide for their families. A part of this training is the duty to oppose evil, and if necessary, to oppose it with deadly force. Manhood and martial virtue are very closely connected in historical terms.

We are in an age that does not want to believe in manhood, at least the traditional kind. Men are not supposed to be strong today. They are not supposed to lead their families. They are not supposed to take ownership of provision for their household. They are not supposed to be fearless. Modern men have had their innate manhood bred out of them.

As a result, many men today don’t want to sacrifice for others. They want to be nice, and liked by everyone, and to win the approval of their peers. They have learned to channel their aggression into the default modern mode of critical engagement: passive-aggressiveness, in which you hide your true feelings behind a veneer and attack with subtlety and deception, not forthrightness. They have been indoctrinated to believe that there is no right and wrong, and that the sense of honor that bubbles up within them–a desire to stand for what is good and true–is silly, embarrassingly earnest, and outmoded.

We want to be snark artists today. We don’t want to be cowboys.

Against this backdrop, American Sniper is a rather shocking entrée. It presents a simple man who lives by a black-and-white moral code. He is traditional. This is not existential manhood; this is non-existential manhood. Kyle does what he thinks he should do, and does not second-guess himself. He believes that he should use his God-given strength and ability to defend the weak and defeat the wicked. He believes, in fact, that there are wicked people in the world. He is not afraid to say so. He is not afraid to act on this conviction.

Clint Eastwood’s movie is not a celebration of death. There is nothing Rambo-like about what Chris Kyle does in the movie (based on his best-selling book, which I read two years ago in a flurry of discovery). He is a killing machine, and he is fearsome to behold, as are his fellow SEALs. But while Eastwood clearly believes that these men are courageous and doing valuable work, he does not glamorize war. War is brutal. It exacts a terrible price. There is no way to pass through it unscathed.

What Chris Kyle does, however, is right. It is virtuous. It involves manhood. More than this, it is a display of manhood. There are many people in America who love seeing manly virtue in action. Hollywood doesn’t make many films or TV series for them (for us); it very mistakenly (and to its own box-office detriment!) thinks that we’re all postmodern now, when we assuredly are not. Postmodernism is a pleasing fiction. It pretends that there is not right and wrong in the world, that men and women are the same, that it is better to live in an amoral gray zone than in a world that depends upon truth and goodness.

All of which collapses when there are terrorists who would, out of a fund of inexhaustible cowardice, kill the innocent for no good reason. American Sniper‘s most harrowing scene comes when a vengeful Islamic warlord named “The Butcher” drills a hole in a little boy’s head. It’s one of the most horrific things I’ve ever seen. But this is realistic. Terrorists blow people up. They maim and torture and butcher the innocent.

There are few men left who will give up their freedom to stop them. But Chris Kyle was one of them, and I was moved to a profound degree by his heroism.

Kyle was no wilting flower. He was not a perfect man. He knew this. He was rough around the edges, he sometimes shot off his mouth, and he had a tough time with rules. In other words, he was a classically aggressive man. Our culture wants to anesthetize such men, to stick a tranquilizer in them and dose them up on medication to tame their natural aggression.

This is not what the church advocates, however. The church gives men a vocabulary for their aggression, their innate manliness. It funnels their God-given testosterone in the direction of Christlike self-sacrifice for the good of others (Eph. 5; 1 Tim. 3). It does not seek to tame men, or ask them to become half-men (or half-women). It asks them to channel all their energy and aggression and skill into the greatest cause of all: serving the kingdom of the crucified and risen Christ.

This men may do as single men, free to serve God with abandon like the apostle Paul. This they may do as married men who win a woman’s heart, raise children, lead their family members to know the Lord and serve the church, work hard to provide, and give their strength and energy to protect and bless their household. Modern men have been told by the New Sexualism to disdain this leadership project, and instead to gratify their lusts alone. As a result, modern men have taken a nose-dive.

The remarkable thing about enfranchising men as leaders is this: it’s exciting to women. Women are hard-wired to want men to be virtuous, not selfish. Modern women have been taught to oppose, compete with, and disdain men. But many of them crave the exercise of virtuous manhood on their behalf. The most interesting sociological nugget I picked up from my viewing of American Sniper was this: the presence of numerous young women in the movie theater.

For many women, a virtuous man is inspiring, even thrilling. This was true for Taya Kyle, who is a woman of faith and courage. Whether a man is a war hero, an electrician, a professor of literature, a pastor, or a Home Depot staffer, if he is honorable and self-sacrificial, women will appreciate him. You need not bench press 350, as too many young men think, to impress a young woman. You might be short or you might be tall, but if you love truth, stand for what is right, and sacrifice your time and energy to strengthen others, you can be a hero to someone.

That’s what I think the women–and the men–who have turned out in droves to American Sniper want. They are desperate to believe in men. They want to see virtue in action. They want to believe that men can be something greater than snarky, self-protecting, self-interested, fearful boy-men who refuse to grow up. They want to be reminded that men do exist who will take on terrible risks and terrific responsibilities, who will put such burdens on their shoulders, and carry them all the way until the work is done, and evil lies cold in the dust.

That, after all, is what is so thrilling about Christianity. The faith at its apex bears witness to a man. He was fearless. He was brave. We don’t know how big his shoulders were, or how handsome he was, or how fast he could run. We do know that he laughed in the face of evil, and gave no quarter to his opponents, and did not apologize for claiming that he was the way, the truth, and the life. Even as death took him down, he struck a climactic blow against the kingdom of darkness. He crushed it. He ended the reign of Satan, and began the true reign of the Son of God. Jesus was not a pacifist. He was a conqueror, and he will return to judge the quick and the dead.

When we see a hero, an imperfect man, like Chris Kyle taken from us, we are seeing a very, very small picture of the ultimate hero. It’s like a flash of sunlight that passes through a room in an instant. For now, good and godly men–and I believe that Chris Kyle was a Christian, based on his clear testimony–must suffer violence. They must die.

The end of American Sniper is the most poleaxing conclusion to any film I’ve ever seen. The fact that I knew that Kyle was going to die the whole way through the movie was almost unbearable, and then Eastwood closes the film with a single trumpet playing against a backdrop of images from Kyle’s funeral. I was moved to tears. Writing this, I am still moved to tears. This movie left a mark on me, as it did for so many others.

The terrible truth about even virtuous manhood is that it must pass away in this life. Death still rules. But there’s something yet to come: our hero will return. Unlike every other man, he came back to life. On the last day, he will come, and we will meet him in the air. Then, all of our expectations will be fulfilled. All of our hopes will be met.

The true man, who redeemed us, will lead us into a world where heroes do not die, but live forever with their God.