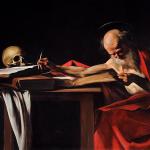

Dettaglio dell’Arca di San Pietro Martire nella Cappella Portinari della Chiesa di Sant’Eustorgio a Milano. Sotto: Statue delle Virtù. Sopra: Formelle con storie della vita del santo. Foto di Giovanni Dall’Orto, 1-3-2007.

Picking up where we left off last week, we’ve come to understand why Saint Thomas considers a hatred of activity an impediment to beatitude. But to fully understand this aspect of acedia, it’s necessary to acknowledge that to Saint Thomas activity also carries the virtue of charity.

But this is Saint Thomas we’re talking about here, so don’t assume that our contemporary (or your personal) definition of virtue is what Aquinas has in mind. Saint Thomas defines virtue as habitus – which (and please correct me if I’m wrong) I’m interpreting as something which is acquired through repetition. It’s much broader and inclusive that our modern notion of a “habit” and contains a qualitative distinction as well. Perhaps it has more in common with “a positive cultivation of the good”? Anyway, in driving this difference, home Nault refers us to the “magisterial” Fr. Servais Pinckaers, O.P. essay “Virtue Is Quite Different from a Habit” (NRT, 1960: 387-403, reprinted in Le renouveau de la morale: Études pour une morale fidèle è ses sources et è sa mission présente, Cahiers de l’Actulité Religieuse 19; Tournay: Casterman, 1964), which says that, even though virtue and habit are both acquired through repetition, virtue involves interior as well as exterior acts. It was William of Ockham writing a century after Saint Thomas who, conflating habit and virtue, “would opine that virtue is an obstacle to human freedom”, Nault writes. Nault goes on to say that:

Of course, if you are shaped by habits, you lose part of your freedom; but, strictly speaking, virtue is not a habit. It is an extraordinary inventive capacity that enables us to carry out excellent acts that are profoundly in conformity with God’s will. It is a stable disposition to do good.

Saint Thomas lays out an exhaustive and complex rendering of human action in twelve steps, the last of which is choice. But within this process he also draws a distinction between operative habitus (something that enables us to act, a capacity to cultivate and perfect action) and elective habitus (the capacity to choose). Virtue is both of these things. It not only allows us to choose good, compels us even, but it makes us good in the choosing.

To grasp the heart of the difference, we have to question our contemporary notions of freedom, which we feel are incomplete without the ability to choose evil (or simply stuff that’s bad for us). In this simple calculation transgression itself becomes construed as an act of freedom. But the opposite is true, as anyone who has experienced a master musician or professional athlete can recognize. They practice their scales and run drills (habitus) in order to gain even greater freedom and perform “excellent actions easily and joyfully”, as Nault puts it. Would we listen to someone hitting a million dud notes on a guitar and say “Wow, look at how liberated that musician is”? What about a guitarist that was able to finish a song perfectly even though a string broke in the middle? Which person is more free?