The story is told of a logician/mathematician at a university where Karl Barth once taught, demanding that the Swiss theologian answer the following question, “What gives you the right to teach at this university?” Barth responded, “The resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead.”[1] Some might scoff at Barth’s answer. Some might be surprised. After all, the answer comes across as, well, so unscientific. But is it? I supposed it all depends on how Barth—or others making a similar claim—understood the relation of Jesus’ resurrection to history.[2] Can one make a case for the Christian faith as a historical discipline, in a way similar to Wolfhart Pannenberg’s theological program?[3] Or is it the case that the account of Jesus’ incarnation and resurrection opens up new vistas for approaching various dimensions of reality, as in T. F. Torrance’s theological enterprise?[4]

In any event, I want to continue with this train of thought by particularizing the question to each Christian: “What gives you the right to be a Christian?” Is it simply a matter of opinion, as the Dude says in response to the Jesus figure’s taunt in The Big Lebowksi? “Yeah, well, that’s just, like, your opinion, man.” Or is it something like the response exponents of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism[5] might offer? “Who said anything about right? It’s a preference.”

Clark Pinnock weighed in on the discussion years ago with his slim volume, Reason Enough: A Case for the Christian Faith.[6] There Pinnock deals with pragmatic, experiential, cosmic, historical and community bases for presenting the Christian faith as credible. The point of this post is not to prove the Christian faith to anyone, as if that could be done. If anything, I simply invite my fellow Christians to consider avenues for discussion that they might offer in response to the opening question. Pinnock provides various avenues for consideration. Perhaps there are others.

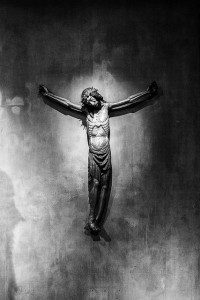

In closing, I return to the possibility that some individuals today might view their faith in Christ simply as a matter of consumer preference. This stance is quite unfortunate in that any commitment based on mere preference is one easily abandoned. Worship involves not simply reason but also action and passion: we should be passionate about what we believe, so much so that we will hold firm even if our faith costs us discomfort—or more—like our Coptic Christian brothers and sisters who have suffered greatly at the hands of ISIS. Perhaps skeptics in our midst will never accept our reasons for faith; but just perhaps, they might find striking that we really believe, come what may. As I wrote in my book New Wine Tastings, the verdict that Jesus is Lord demands evidence in our lives that he is Lord.[7] He is worthy. Will we demonstrate the rightness and supreme beauty of our faith with congruent lives?

______________________

[1]See the account of this anecdote in Colin E. Gunton’s The Barth Lectures (ed. P. H. Brazier: London: T. & T. Clark International, 2007), page 44.

[2] Some argue that Barth was a fideist; however, they do not realize that Barth was working within a broader definition of rationality than mere empirical reason. See: Kevin Diller, Theology’s Epistemological Dilemma: How Karl Barth and Alvin Plantinga Provide a Unified Response (Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2014). See as well T. F. Torrance’s letter to Brand Blandshard of April 11, 1952 published in The Scotsman on April 14th, 1952.

[3] Wolfhart Pannenberg, “Redemptive Event and History,” in Basic Questions in Theology, vol. 1 trans. George H. Kehm (Minnesota: Augsburg Fortress Press, 2008), pages 15-81.

[4] T.F. Torrance, Space, Time, and Incarnation (Great Britain: T&T Clark, 1997); see also T.F. Torrance, Space, Time, and Resurrection (Great Britain: T&T Clark, 2000).

[5]See the discussion of this term by Christian Smith and Melinda Lundquist Denton, Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

[6]Clark H. Pinnock, Reason Enough: A Case for the Christian Faith (Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 1997).

[7] Paul Louis Metzger, New Wine Tastings: Theological Essays of Cultural Engagement (Eugene: Cascade Books, 2011), page 20. G. K. Chesterton also wrote on the relation of faith to practice: “The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting. It has been found difficult: and left untried.” G. K. Chesterton, What’s Wrong with the World (Feather Trail Press, 2009), page 18.