There is an old Protestant Reformation doctrine associated with Martin Luther “Simul Justus et Peccator” (simultaneously wholly righteous and sinful)[1]. Apart from our union with Christ, we are completely unjust, unrighteousness. However, those who respond in faith to the good news of God’s grace through Jesus Christ are completely just and righteous in total dependent relation to him. This dialectical reality remains constant throughout the Christian’s life, highlighting total dependence on God’s mercy.

Does the same kind of dialectical reality remain constant with us as humanity in terms of violence and war, or are they on the decline? Here is another way of putting it: Are war and violence declining, or simply becoming more advanced by proxy, drones, and other vehicles, so that we are ever advancing, yet ever regressing?

Advanced countries’ ability to destroy the world many times over is one deterrent for the major powers going to war, so argues John Gray in his critique of Steven Pinker’s thesis in The Better Angels of Our Nature: A History of Violence and Humanity that war and violence are on the decline and altruism is advancing. For Gray and others, this presumed deterrent may lead such nations to wage war through other means, fearing the unimaginable devastation of contemporary nuclear technologies that far exceed the horrific power of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (For example, see this Business Insider article).

As alluded to earlier, wars waged via ‘lesser’ powers (proxy) and through remote agents and AI technologies may serve to further advanced nations’ reach and influence regionally and globally. The point here is not to deny altruism, but to distance ourselves from naive optimism pertaining to ‘civilized’ cultures. As Gray indicates, “There is no reason for thinking human beings are becoming any more altruistic or more peaceful” and “There is something repellently absurd in the notion that war is a vice of ‘backward’ peoples.” (For an article addressing why humans find it so difficult to live in peace, see this piece in Psychology Today); it should be noted that the author holds out hope for the future based on Pinker’s study, and gives reasons for why we are experiencing in his estimation more peace today. Elsewhere it has been argued against Pinker that while battlefield casualties are declining, the same cannot be said for civilian fatalities).

I wonder if those who hailed humanity’s progress in Germany prior to WWI would have considered themselves backward? The ‘advanced’ nations of the world known as Germany, England, France, Italy, the United States and Japan waged war during both world conflicts. Though the U.S. and Japan, for example, were allies during WWI, they became bitter enemies at the time of the Second World War. Whether one reminisces over the fatherhood of God, brotherhood of man progressive eschatology prior to WWI or a progressive brotherhood and sisterhood of humanity secular creed today, it is worth recounting Reinhold Niebuhr’s challenge to utopian visions with biblical realism involving consideration of the negative aspects of power structures and human sinfulness. At the very least, his social ethics provides us a healthy dose of caution.

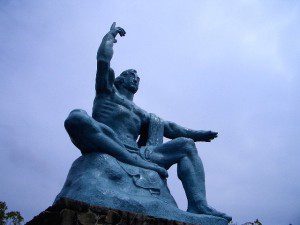

I applaud the robust exhortations of the Japanese people here in Nagasaki (where I write this post), who cried out for a world free of nuclear warfare at the time of the atomic bomb memorial here on August 9th. It is also wonderful that the world has come together for the Olympic Games in Brazil even in the midst of fears over Zika and the global threat of terror. It is far better seeing countries ‘go to war’ peacefully on the race track and gym mat and in the swimming pool than in the jungles or deserts, on city streets, and the high seas. Still, remember that Adolf Hitler presided over the Olympic Games in culturally advanced Berlin in 1936 and was TIME Magazine’s Man of the Year in 1938. What became the Second World War started a year later in 1939 with Hitler’s and Germany’s invasion of Poland.

I do not see myself as an optimist or pessimist, but as a biblical realist, and one who believes we are ever advancing, ever regressing as a species. With this in mind, I can concur with President Obama’s call at Hiroshima earlier this year to proceed with a moral revolution to complement our technological advance as a species. For me, in light of the claim that we are ever advancing, ever retreating, this moral revolution must begin anew daily.

____________________

[1] While the Latin here simply stated signifies that the Christian is simultaneously righteous and a sinner, I have added “wholly” in that as I understand Luther’s view of union with Christ in such treatises as “The Freedom of a Christian,” there is no sense of such categories being partial. They are total. Apart from union with Christ, we are totally depraved. Through union with Christ, we are wholly righteous, for we are clothed in him by faith in his person by grace. To quote Luther, “Who then can fully appreciate what this royal marriage means? Who can understand the riches of the glory of this grace? Here this rich and divine bridegroom Christ marries this poor, wicked harlot, redeems her from all her evil, and adorns her with all his goodness. Her sins cannot now destroy her, since they are laid upon Christ and swallowed up by him. And she has that righteousness in Christ, her husband, of which she may boast as of her own and which she can confidently display alongside her sins in the face of death and hell and say, “If I have sinned, yet my Christ, in whom I believe, has not sinned, and all his is mine and all mine is his,” as the bride in the Song of Solomon (2:16) says, ‘My beloved is mine and I am his.’” Martin Luther, The Freedom of a Christian, in Martin Luther’s Basic Theological Writings (ed. Timothy F. Lull; Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1989), 604.