[Read part one here, and part two here]

5. Forgive others and yourself.

Part of the power of the Christian faith is the power to love and forgive one’s enemies. Jesus forgave his enemies on the cross (Luke 23:34), and calls on his followers to love their enemies, pray for them, and forgive them (Matthew 5:44; Matthew 6:12, 14-15). Torture affects the tortured and torturer alike, in addition to others (Refer to these articles by The New York Times, Christian Science Monitor, and Sydney Morning Herald). We must bring the cycle of torture to an end, just as Jesus brought an end to the cycle of violence on the cross, bearing it in his own person and thereby absorbing it as he alone could do as the God-Man.[1] Otherwise, wounded people will continue to wound others through violence, torture, and the like.

It is also important for those who have suffered at the hands of others to forgive themselves for failing to live virtuously in the midst of suffering. God calls on us to forgive others, as God has forgiven us. So, if God has forgiven us, even as we ask for forgiveness, why can we not forgive ourselves in addition to others?

Forgiving others and ourselves is key to addressing the trauma of persecution and torture. It is also important for those who serve as wounded healers—those who have been wounded and who forgive others and themselves—to build trust with those who come to them in their effort to find healing from their own experiences with persecution and torture. Identification involves empathy. Just as the wounded healer has come to terms with empathizing with the torturer in their weakness and with themselves as tortured, they must come to terms with the weakness of their fellows who have also been the victims of persecution and torture. Such identification involving empathy is key to the transformation process. Ellen Gerrity, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Duke University (and co-editor of “The Mental Health Consequences of Torture”), appears to get at this theme in the following statement:

The healer and the torture survivor must establish trust so the survivor can better understand what happened and forgive others, as well as himself or herself,…Bearing witness to the story is a large part of the healer’s role.

Olympian Louis Zamperini, whose story was made into a book and later a movie titled Unbroken, was a POW during WWII in Japan, and was horribly persecuted along with others by his captors. Sometime after being released, he came to faith in Jesus Christ. He later realized the need to return to Japan to express forgiveness to those who had tortured him. He realized how healing it was to forgive others. Forgiveness is important to the tortured and torturer alike. Drawing from a quote attributed to Mark Twain, he claimed that “forgiveness is the fragrance that the violet sheds on the heel that has crushed it” (Refer here). The same fragrance permeated from the cross of the Nagasaki martyr Paul Miki, who from the cross spoke not only of the privilege of dying for Christ’s cause, but also of his obedience to the Lord’s command to forgive his enemies—including the Japanese overlord Hideyoshi (who gave the crucifixion edict). Paul Miki preferred love over hate and desired instead that all Japanese become Christians (Refer here).

6. Fight persecution and torture of all peoples and religions.

One of the most important ways that Christians can operate in a pluralistic age is by caring not simply for their own freedoms, but also for those of others (Refer here to a prior blog post at this column addressing this theme). Of course, this should be Christians’ concern no matter how homogeneous or heterogeneous the culture. Still, for those deeply fearful of the apparent loss of their freedoms as Christians, it won’t help simply to demand freedoms. In fact, for Karl Barth, it is never right for the Christian to demand rights from the state;[2] for Barth, a demanding posture is a denial of the freedom of the good news of God’s grace revealed in Jesus. Our uncommon, gracious God cares for the common good—even when he was tortured unto death. Rather than demand, he exemplified the new state of gracious being—one that forgives others their debts and cared for people no matter their response to him and his claims. He is the same yesterday, today, and forever. Thus, his followers must care for the well-being of others, including those of other faiths and alternative points of view who also undergo persecution and torture.

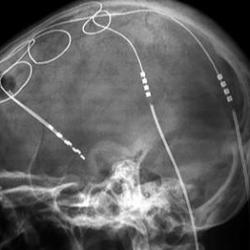

The early church sacrificed greatly for the common good, including providing healthcare under very trying circumstances, even when persecuted horrifically, as a Christianity Today article highlights. In like manner, the church today must seek to alleviate the suffering of others, wherever it appears worldwide, including the victims of persecution and torture. In an age where torture and trauma are wreaking havoc on our global soul (Refer here to a CNN article, a Newsweek article, and still another article from CNN), the church can embody and empathize with others in their suffering through the freedom that comes through faith in Christ—the ultimate wounded healer[3] who takes upon himself the trauma of the world. As with Endo (noted in a previous post in this trilogy of essays), it is this compassionate Christian faith—not high and lofty cathedrals or militant, triumphalist Christendom—that alone can and must take root in Japanese, American and even Syrian soil. Such compassion alone brings wholeness to our fragmented souls.

During this very political season, when many are experiencing trauma, and persecution complexes in some cases, it is my hope that we who are Christians will take our cues from our Lord and from believers throughout the centuries here and abroad. May we not return the favor and wound back when wounded. May we become wounded healers.

______________________

[1]See G. B. Caird, Principalities and Powers: A Study in Pauline Theology, with a foreword by L. D. Hurst (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2003). In his work, Caird writes, “Evil is defeated only if the injured person absorbs the evil and refuses to allow it to go any further.” See my blog posts at Patheos accounting for this theme and its bearing on addressing violence and torture in our day: “Zero Dark Thirty and Zero Sum Gain.” Martin Luther King, Jr. was the greatest proponent of this Christian virtue in our contemporary age.

[2]See Karl Barth, “The Christian Community and the Civil Community,” in Against the Stream: Shorter Post-War Writings, 1946-1952, ed. R. G. Smith, trans. E.M. Delecour and S. Godman (London: SCM Press, Ltd., 1954), pages 30-31; see also my blog post titled “I Can’t Wait for Christian America to Die.”

[3]Henri Nouwen wrote of how our shared human condition of wounded-ness can serve as a source of healing when counseling others. Ministers must operate in view of the suffering image of Christ as the ultimate wounded healer. See Henri Nouwen, The Wounded Healer: Ministry in Contemporary Society (New York: Image Books, 1979).